The work of San Francisco artist Aron Meynell doesn’t immediately command attention. His tones are muted—“somber” is how White Walls gallery owner and curator Justin Giarla put it—and his subject matter that which might be swiftly passed over in the work of a less-skilled artist: trees, animals, the occasional person. But to round down the quietude of these pieces to silence would be an underestimation of their power. Instead of choosing to shock or scream, the carefully constructed landscape studies comprising Meynell’s first solo show hum along almost inaudibly, their worlds not quite plausible but not easily rejected as fantasy.

Framed inside White Walls’ cavernous space on Larkin Street, Meynell’s interpretations of ruin and renewal amplify themselves. With its extensive canvases and clear mastery of the properties of light, the show creates a cathedral-like vacuum within the gallery. The sense of absence is so magnetic that it warps into a sort of presence. And though the overall palette might be slated as post-apocalyptic, each piece in the collection resists sure definitions; at times, the environments are so surreal as to be alien, while at others they’re clearly the remnants of a realm much like our own. Given Meynell’s background, it’s easy to decode the genealogy of his influences: before graduating from the San Francisco Academy of Art, he grew up in Detroit and became fascinated by the structures left in the wake of the Motor City’s once-booming industries.

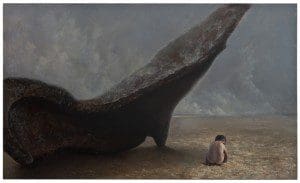

This obsession is apparent, if not always explicitly, in every work on display here. Consider “Beached,” in which a naked boy, overshadowed by a gargantuan rudder or fin that’s washed in from the ocean, crouches on a plane of sand. The first inclination is to allow the masterful invocation of seaside fog to take precedence. But the longer the eye moves from the remains of some beast or ship to the child, the less the gray haze seems dismal. These aren’t outright happy paintings, of course; the surface impressions are those of destruction. But instead of swinging his viewfinder’s eye onto the terminus of human existence, Meynell juxtaposes often multi-layered symbols to offer us the possibility of an alternative.

Putting aside the quandary of considering an artist’s intention when assessing his work, Meynell’s stated goals are, in some regard, confirmed in his paintings. “The purpose of my work is to depict characters unconcerned with the barrenness that wreckage and isolation can embody,” he writes on his website. “These are interactions fueled by the freedom of being alone…” Indeed, Meynell’s paintings, though indirectly confrontational through their seeming dreariness, resolve themselves neither as elegies for past worlds nor as preludes for new ones.

If anything, the unsettling quality of these near-parallel netherworlds can be traced to how they hold fragments of our familiar surroundings captive: rusted metal components, mostly, and other relics of a fallen empire. Still, the eerier aspects of Meynell’s work—some of the pieces’ most promising traits—are never garish in how they disturb. In “Child With Machine,” the image of an infant alone in a field dwarfed by an organ of machinery similar to that in “Beached” conjures a thousand hypotheses as to how it got there. “The Return,” in which a pack of pigs appear the size of figurines against the hugeness of a cave, questions conceptions of scale and hierarchy.

Thankfully, Meynell is not interested in dispensing instructive lessons about the perils of politics, war, or industrialization. Rather, his vantage is one notch past the Omega Point. The term, invented by French Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in 1950, refers to the rumored apogee of complexity that, once reached, prompts the universe to reset itself. In these provocative paintings, evidence of a violent history is dovetailed into the woodwork of placidity. Convoluted mechanisms, vivisected from their apparatuses, distill to raw materials. Humans become afterthoughts. In the context of a second genesis, the ashen caul over Meynell’s work seems always as much the mark of a phoenix-like beginning as an ending. Eventually, weeds will grow up through the factory floor; the earth will reclaim itself.

The work of mixed-media artist and San Francisco native Erik Otto, however, couldn’t be more different in apparent aims and aesthetic. Otto, whose exhibition Tomorrow Is Never Promised ran at White Walls in 2010, brings a focused energy to the experiments making up The Project Room, his most recent offering at White Walls. Among these paintings and collages (receipts and cutouts from operational manuals are grafted facedown onto several of these pieces) is a sort of barely-reigned-in mayhem of scrapyard slats and house paint, the latter arresting in its neon monotones. Uninterested in concealing or disowning the quirks of his medium, Otto lets the cracks and knobs in the planks become integral to his finished products. Cumulatively, these external elements blend in almost effortlessly with their painted counterparts; most of these pieces invest themselves in explorations of geometry and form—and ways these boundaries can be defied.

In “Flux 1” and “Flux 2,” a white disc of sun is obscured by blue-black, looping curls of vapor. Hard edges abound, from the perfect circle of the work’s centerpiece to the rays shooting from it, and even the trapezoids and rectangles comprising the beige background. “Warming,” a piece filled with swooshed brushstrokes in tangerine and cherry hues, compliments its thermal antithesis “Cooling,” fostering the perception of a yin and yang-esque clash not only within individual works in the collection but among separate pieces engaged in dialogue with each other.

Given that The Project Room consists of so many serial compositions, such a non-linear debate on the meaning of form—or on its converse, formlessness—is inevitable. The curves of “Flow Like Water 1” and its subsequent permutation call to mind a land-like physicality that, at once, is also reminiscent of liquid or gas; viewed side-by-side, distinctions are even more impossible to entertain. Otto’s work throbs to a boiling-water frenzy: each of his creations’ ingredients are throttled to their limits. If Meynell has crossed the line of the Omega Point, Otto is approaching it with increasing velocity. Perhaps nowhere is this better embodied than in his “Frequency 1” and its corresponding piece, “Frequency 2”: over a white backdrop, sharp triangle fragments hover over the rim of a colorless abyss. The black circle seems to possess powers of gravity—a portal dragging those shards toward that place where one thing reassembles into another, to where matter becomes light and light matter.

Whereas Meynell’s movement is glacial, Otto’s is both continuous and anxious with a motion uncertain of its direction. These artists together under one roof, however, present the same set of questions articulated two different ways. Eventually, they each reach a climax of their own, a culmination at which uncertainty brims over into true aimlessness: maybe Otto’s orbs are unable to be contextualized, and Meynell’s atmospheres static as opposed to transitory. And this smearing of the cycles that they themselves have proposed is, in the end, what Meynell and Otto have most in common. Colossuses will fall, establishments of industry will rust; previously identifiable shapes will morph out of their identities. Relativity will, in a quick and terrifying moment, take over. But these two artists demonstrate how that moment can also be exhilarating—the mere fact of the artworks’ observation means that the viewer, if only for a shred of a second, exists somehow in concrete connection to another object, anchored by the drama of whole dimensions as they collapse or emerge.

New Work by Aron Meynell and The Project Room by Erik Otto run through August 27 at White Walls, 839 Larkin St., San Francisco.