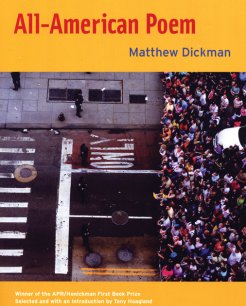

Matthew Dickman’s first book, All-American Poem, received the 2008 American Poetry Review/Honickman First Book Prize in Poetry, and his second book is slated to appear in 2012 from W.W. Norton. Featured in ZYZZYVA’s Spring 2011 issue, Dickman’s work has also appeared in The New Yorker, AGNI Online, and Tin House, where he works as an editor. The twin brother of poet Michael Dickman, his poems function as both paeans and laments of the zeitgeist of modern American life — tessellating mythology with reality, Beat zeal with modern nods toward restraint.

The Oregon native sat down with ZYZZYVA at Stumptown Coffee in Portland to talk about his work in the Spring 2011 issue, craft, the writing life — and Jay-Z and art’s fight against meanness, among other things.

ZYZZYVA: Your bio in the Spring 2011 issue says you work as a grocer at Whole Foods. You’re the winner of several prestigious prizes and fellowships. Do you have work in any capacity in an academic setting, or see yourself as an academic writer?

Matthew Dickman: There are four ways, really, that I pay my bills, the smallest of which is going and doing readings — I mean small as in fiscally small; I don’t make enough off of readings to pay all my bills and stuff. But I love doing readings, and I’m also the Associate Poetry Editor at Tin House, which is, for me, really meaningful because Tin House was the first national magazine to publish any of my poems. Back in ‘99 or 2000, they took two of my poems for their New Voices section. I remember when I got their acceptance letter, which was the first acceptance letter I’d ever gotten, I totally freaked out about it. Then, eleven years later, I get to be a part of their great magazine. I teach here in Portland at the writing center called the Attic Institute, where I teach some community workshops. Then I work off and on for the Vermont College of Fine Arts. So a lot of it’s teaching, and that kind of thing. But I don’t belong to a university.

Z: Do you feel that there are any benefits from not belonging to a university? Is that even something you aspire to at one point, or are open to?

Dickman: I think it would have to be a special circumstance for me. There are certainly a lot of reasons to work for a university, in an MFA program, and I have amazing mentors and friends who publish amazing books of poetry and fiction who have worked for a university full-time through the years. But for me, I just know myself well enough that I don’t think I would do very well with a lot of the paperwork and a lot of the bureaucracy. So I’m trying to figure out a different way to live my life. You know, there’s a prescription: first you’re interested in creative writing as an undergrad, then you do your MFA program, then you do a Ph.D., even, and then win a first-book contest and start teaching at a university. But I think there are other ways to live your life, too, which is fine.

Z: Your second book of poems is scheduled for next year. Can you tell us a little about that?

Dickman: So it’s my second book of poems, and it’s going to be published through Norton in New York. I’m lucky enough to have Jill Bialosky as my editor. We’ve already had some amazing conversations. The core of the book is a thirteen-part elegy for my older brother Darin, who committed suicide about four years ago now, and there are poems in other sections of the book that deal with a couple friends who died in a similar way. That’s definitely a thread. There are also love poems in the book. For some reason, there seems to be a lot about space in the book, whether it’s stars, or planets, or the unknown, but it’s a more somber book than All-American Poem was. I mean, there’s still some humor in it, but it is quite a different book. It’s formally a different book, too, in that a lot of the poems are much shorter. In my first book a lot of the poems run at least a page and a half. In this book a lot of the poems are about twenty lines, or fewer.

Z: Speaking of space, your poem “Dear Space,” which appeared in ZYZZYVA’s Spring 2011 issue, seems to comment on beginnings and endings while being transposed from this central vantage point of stasis — of being in the middle, of being lost. “The Bridge” also has this vibe of being untethered, this frustration with free will either failing or decaying (“This choice / I think I have.”). What is it about this sensibility that makes it a recurring element in your work?

Dickman: For me, part of it is the idea of loneliness. In “Dear Space,” it’s being alone, and walking to a park at night. And then “The Bridge” is sort of describing being with people in the beginning, the strange drunk girls at the start of the poem, and then being alone on a bridge. I think loneliness and the fight against loneliness is something that I deal with in my own life. But also, no matter where you are, there’s still the world around you. Whether it’s standing on a bridge and wondering if you have a choice between jumping off it or staying on it, even while you’re standing there on the bridge, cars are racing by behind you, there’s a whole life around you.

It’s the same with “Dear Space,” when the narrator goes into a park at night, there might be a bird, and the bird might be dead, but there might be a living dog holding the bird in its mouth. And then always for me — and this may be a romantic desire — but the desire for people to be OK, myself included. And the bird, I want the bird to be okay, too. I think that’s one of my concerns just as a person trying to deal with my own mind, my own life.

Z: I’m struck by the heavy anaphora in parts (“Dear love. / Dear motherfucker. Dear heart. / Dear space, I want to write — “) of this piece, and in other pieces of yours. They’re almost Whitmanesque lines, like chanted invocations. Is this repetition planned, or something that unfolds as the rhythm of a piece evolves?

Dickman: That was definitely spontaneous. Years and years ago when I would write poems, much of what I wrote was totally planned. I would think about it a lot beforehand. I would write down a little sort of “schedule” for the poem. But then around 2001, 2002, I had kind of an emotional breakdown and had to take time away from school and life to see my therapist and figure stuff out. And I ended up not writing for almost eight or nine months. When I came back to it, after I felt like I was an emotionally responsible person again, all these rules that I had beforehand were kind of gone. So now when I sit down to write a poem — and I think a lot of people write like this — often it is a simple idea that comes to mind. And then whatever comes out when I’m sitting down sort of just comes out. Of course, I’m also very interested in rewriting. But that moment you’re talking about in “Dear Space” wasn’t a rewritten moment. It was more of an immediate feeling of desperation. And I think we all have that feeling, you know, “Dear someone — fuck! — dear someone!”

Z: “King,” your poem in The New Yorker (November 1, 2010), speaks with rending honesty and imagination about the death of your older brother. Was there a point where that experience seemed like something beyond the purchase of what poetry could address?

Dickman: No! Not at all. I believe that no matter what we write, we are writing out of two human experiences. One being ecstatic love, and one being deeply felt grief. I think that both these experiences destroy language, and that poetry is maybe the best written-art form to build a language out of the rubble they make of life. So no, I never thought that my older brother’s death, or any other experience I’ve had, was sort of out of bounds of poetry. But then writing about his death — and always, whether it’s writing about someone’s death, or writing about wanting to sleep with this amazing woman, or even having some sort of ecstatic moment in nature — I think it’s always the case that I’m writing to understand the world around me, and to better understand who I am within that world. It’s not really therapy, but it might be therapeutic.

Z: The poem seems to retool the experience of the grieving process, foregoing a more factual description of a sequence of events. To what extent — if any — do writers, poets, have an obligation to “fact” when describing such experiences? Is this even possible?

Dickman: I don’t think there’s a point to it. I’m not even sure it’s possible to write it that way in a poem, because X and Y and Z happen in the physical world. But certainly, that poem “King,” besides being written out of my life, is also, in another way, not my life. And what I mean by that is that poetry does not exist in the physical world. I think poetry is how we understand the physical world. There’s no metaphor or simile in the physical world. The father who puts his cigarettes out on his daughter’s arms — that’s physically happening. That’s not a metaphor for anything, that’s not a simile for anything. You have an orgasm, that’s not a metaphor for something else — it’s chemical, it’s real. It’s like this great thing that teachers tell their students, and it sounds very Buddhist, “Write what you know.” Which sounds really awesome, but really, it’s all we do. It’s all you can do.

Z: While putting forth several provocative ideas about modern American life, the title piece of All-American Poem seems to host a speaker who’s in a constant state of negotiation, of compromise, with the world, even down to the poem’s last lines: “Tom Petty is singing about a girl from Indiana / and I am buying you another drink. I am trying to take you home.” Given the poem’s title, how does this sensibility factor into the American identity at large, as abstract and vague an entity as that is?

Z: While putting forth several provocative ideas about modern American life, the title piece of All-American Poem seems to host a speaker who’s in a constant state of negotiation, of compromise, with the world, even down to the poem’s last lines: “Tom Petty is singing about a girl from Indiana / and I am buying you another drink. I am trying to take you home.” Given the poem’s title, how does this sensibility factor into the American identity at large, as abstract and vague an entity as that is?

Dickman: Well, I think one thing that’s not vague about the American identity is the idea of hopefulness. For all of our cruelties and all of our confusion, I think we are a young, hopeful country. And we’re also naïve, which adds to our sort of ignorant, “let’s party” attitude. It’s hard to see it when you’re in it, and I certainly probably don’t any more than anyone else, but I get the feeling that there’s a sincerity to this country, along with all the ugliness and everything else. This is one of the points for me about that poem: It was my all-American poem, and everyone else will have their own. And that sounds really simple, though I think some of the most simple ideas in art are often the most important ones. But for me it’s Tom Petty, and the “let me buy you a drink” in that moment in the poem. I mean, life is fucking awful a lot of the time, you know? We’re really mean to one other, we’re mean to ourselves. And so I think sometimes, when I’m sitting down in this moment of freedom to make some piece of art, I want to fight that.

There’s a great poem by Gerald Stern, “Your Animal,” and he has this whole poem about ducks and going down to the park and seeing all the baby ducks and all this, and how he loves ducks and how wonderful he thinks they are as animals — but also, how wonderful they are to eat. You know, orange duck, and all these different ways to prepare duck. But at the end of this very emotive poem, he kind of puts his stare back onto himself, and says this poem is “my victory over meanness.” And I really like that. I really like that art is a fight against meanness. And so when I sit down and write, that’s in the back of my head.

Z: The poem also oscillates from talking about Elvis, mini-golf, and Pepsi to post-traumatic stress disorder and the mutilation of war: “He had a friend from Colorado / who got his hands cut off, slow, and forever. His pal / from New Jersey was thrown into the sky / like a human constellation of broken teeth.” Then, “You can go / from one state to another and still feel pretty good about enlisting.” There’s a dark flippancy at work here. What was your main objective with such sharp juxtaposition?

Dickman: Well, it came naturally. I don’t think it was really planned. The deal with juxtapositions is, that’s just life. I really like that Whitman quote about containing contradictions and multitudes. I think we all contain those things, and my life experience tells me that some of those contradictions happen almost exactly at the same time. So there is this fucked-up stuff about war and mutilation that’s horrifying, but even knowing that, human beings still have the capacity to enlist. And I’m not judging that at all. I’m just saying that’s something that’s out there. We’re fascinating animals. I guess those twists in the poem are there because that’s how I see life happening.

Z: Are there problems with using a poetic lexicon that references pop culture alongside Dostoyevsky and death? Are accessibility and depth irreconcilable?

Dickman: No — I think they’re the same thing, actually. If it’s not accessible, you’re not going to feel anything about it. There won’t be any depth. If you can’t access it, if you can’t see your own human in another human, neither of you are going to have a good time at the party. So I think it’s almost one and the same. There’s a lot of depth to our pop culture, the stuff that’s around us. I get weirded out when some people say, “You seem to reference pop culture a lot in your poems.” I don’t really feel like I’m referencing it; it’s all around us, it’s our life. Unless you’re writing about a certain time, how can you write and not have any of your world show up in your poems? For me, if I read a poem of mine and I couldn’t see my world in it, then I’m not sure what the point would be, you know? And there is something fascinatingly deep about Elvis. Talking about mythology — American mythologies, Elvis and Kennedy, are as important as Odysseus, and way more important to a lot of Americans than, say, Greek or Roman mythologies. Our deep history of Classic Literature is important to our culture as human beings, but it may not be that relevant to our brothers and sisters on the bus with us.

Z: It’s interesting that you ask how one can write something without referencing these things. It seems to me that there might be a lot of contemporary poets who’d disagree with you—either vocally, or through their craft, where those references don’t appear.

Dickman: Oh, absolutely. They would, they might. The weirdest thing I ever heard was something someone once about “The Black Album,” a poem in All-American Poem that talks about Jay-Z. Somebody said, “What if, in 100 years from now, no one knows who Jay-Z is?” First of all, both me and Jay-Z are going to be dead, so who cares? Second of all — 100 years, and I say this out of being a fan, I think Jay-Z will still be around. I think there’s this weird idea that if you include something as impermanent as a band or a cola product or a type of car in your poem, that it won’t be relevant 100 years from now. That’s a road to insanity and a type of vanity that I find disturbing. I understand certain people’s aesthetics, but when we’re done having our coffee here, you go back to your hotel, I go across the river, and I mean, I could get hit by a car. I just don’t want to worry about any of those anxieties of what’s relevant and what’s not.

Z: In an interview with From the Fishouse, you recalled first encountering poetry during your sophomore year of high school, when you found Anne Sexton’s To Bedlam and Part Way Back in the library. You also mention Kenneth Koch, who shows up in a dream in “All-American Poem,” trying to take your dog for a walk, of all things. How would you estimate these influences have played out in your work—or, as in Koch’s case, your subconscious?

Dickman: Anne Sexton has influenced me deeply. I think she was a master of image and metaphor, and was one of the first poets I read who I felt was relevant to me in my life. In high school we read poets, but we read Hopkins and Blake and Stevens, which is great, but really wasn’t a turn-on for me at that age. Reading Blake didn’t make me want to fuck or fight, it made me want to take a nap. Now, I’m thirty-five, I read Blake and I find some amazing things in his work, and he’s obviously a genius. But when I was much younger, it was Sexton. She was writing about everything — taking ferry rides to her uterus, for instance. It was awesome. She made me want to write poems.

Kenneth Koch I read much, much later. I wrote over half of All-American Poem before I’d ever read Koch or Frank O’Hara. I was having coffee one morning with a mentor of mine around the time we had just met, and he asked me who I was reading. I told him Czselaw Milosz, Zbigniew Herbert, all of these Polish poets, and some American poets like Yusef Komunyakaa. And he looked at me and said, “No, you’re not.” And I said, “I think I know what I’m reading right now.” Then he said, “What about Kenneth Koch, what about Frank O’Hara?” I told him I’d heard they were really good. He just shook his head and said that those people were my tribe, that I should go find them. So I went and started reading them, and they blew me away. I think the main thing that Koch gave me, and others like O’Hara and Joe Brainerd, was a kind of hallway pass to say anything you wanted to say, that a poem could be written about anything. That’s what I find so exciting about those poets.

Z: “My Father in Russia,” also in the Spring 2011 issue, takes on the hallucinogenic quality of an uncomfortable dream, especially in the scenario it depicts: your father as a Russian mail-order bride. What was the seed of this idea?

Dickman: The poem is about imagining a distant father, but sort of re-imagining my father as a mail-order bride who I then get to purchase and bring to America. I think it’s because when I wrote that poem, I was writing these elegies for my older brother, and so then I was thinking about family a lot. My father and I don’t really know each other, so I feel sort of bad that in the poem he becomes a Russian mail-order bride, but that’s sort of just where it went. But the seed of it, really, was just thinking about a father, thinking about a family member that should be important to you and should affect your life — and does, even in the absence of that person — but who else could they be? They could be anybody. And I think probably because at the time I was writing it, I was living alone on a fellowship out in the middle of nowhere, Texas, I probably wanted to be having sex, and so maybe it was natural if I was like, “Who else could my dad be? Oh, I know! Someone I could have sex with.” I have no apologies or answers for that, that’s just where my brain went, for good or bad.

Z: I read that you staged a posthumous birthday party for William Stafford while an undergrad at the University of Oregon. How has growing up in Portland affected your writing, and how do you see yourself — if you do — as an Oregonian poet?

Dickman: Certainly, growing up in Oregon, you know about William Stafford if you’re reading and writing poems. I love a lot of Stafford’s poems. My poems are nothing like his, except for maybe that they’re narrative in some way. He has such a patience and calmness in his work that I don’t think I have, though I wish I did. So I guess he influenced me mostly in just knowing that there was poetry in Oregon, or that poets could come out of Oregon. As an “Oregonian” poet, in quotes, I think that when people think about poets of the Northwest they think about people writing nature poems a lot, though I don’t really write them because I’m not really out in nature very much, unless it’s writing about a public park or something. So I don’t know if you can look at my work and say that this comes from a certain community or a certain area. One thing about writing on the West Coast, especially in the Northwest, is that I feel you’re away from a lot of the anxiety that my fellow poets sometimes experience on the East Coast. There are no major publishing houses in Portland or Seattle. There aren’t the intense book parties, and money, and all of that — you’re really just out West, doing whatever you want to do. The great thing is that you can do whatever you want to do. The drawback, maybe for some people, is that there are no connections, there are no leg-ups. I don’t know why you’d want them anyway, when what’s more important are friendships.

Z: Are there any sharpshooters to watch out for in your local literary scene?

Dickman: There are some great poets in Oregon. One young poet that’s been published at Tin House recently, whose next book is coming out from McSweeney’s, is a poet named Zachary Schomburg. He’s got a couple of books out, The Man Suit and Scary, No Scary, both by Black Ocean Press, which is this great independent press. But I think Zach is this young, absolutely sincere surrealist poet in many ways. I mean, the first time I read his book The Man Suit, I was just blown away. It reminded me of a young, vibrant, ecstatic Simic. And there’s also a poet who teaches at Reed College, an amazing poet named Crystal Williams. Awesome, amazing poet that everybody should read. Her narrative poems are beautiful and heartbreaking and sometimes funny, she’s a genius with image — the images in her poems are gorgeous.

Z: How important, in your opinion, is a writer’s exposure to other different media—media that they might not ever directly work with?

Dickman: I think it’s wildly important. I think radical change can happen through an artist experiencing other forms of art. I think film is incredibly powerful, and I think you are letting yourself down as a poet, as a writer, if you’re not going out and widening the net of your gaze to visual art, to music, and to film. Especially when it’s different from your own taste buds, what you like. I don’t think I would write what I write — and I certainly wouldn’t have my real life experiences — in the same way if I didn’t search out these other art forms to experience. If you’re a short story writer and all you do is read short stories and write short stories, no matter what happens with your quote-unquote “career” as a published writer, you have to think about your own experience as a human being. I mean, what kind of life is that?