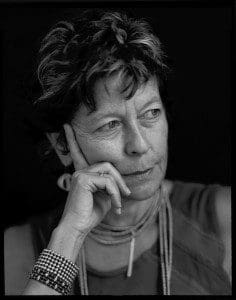

Naomie Kremer has been described as “a remarkable and innovative colorist, with a subtle mastery of intimating interior meaning.” Her current exhibition, “Multiverse Part I,” at Modernism Gallery in San Francisco through April 23, showcases 12 of her densely layered oil-on-linen paintings, all characterized by Kremer’s sensuous use of color, her energetic and meticulous brushwork, and a complex, detailed sense of structure. Yet her work in black and white is integral to her craft, and equally compelling. ZYZZYVA sat down with the Bay Area artist in her bright and inviting studio in Oakland on a recent stormy day. As the rain poured down outside, Kremer discussed the inspiration behind her current show at Modernism, the important role that drawing has played in the development of her craft as a painter, and her innovative collaboration with the Margaret Jenkins Dance Company.

The following images by Naomie Kremer are from ZYZZYVA 46, Summer 1996. For the Record, 1995, pencil & graphite on paper and photocopier. (6×9 inches)

[slideshow id=1]

Z: The paintings in the exhibit at Modernism seem to vividly evoke a very lush and beautiful natural world. When you’re working, do you have a place or scene in mind?

NK: I generally have something in mind. It could be something abstract, such as the light at a certain time of day or in a certain place, or things that I see. I definitely connect with something to begin from. It could be color. In the case of several of the paintings in the show, it’s based on photographs of a dance performance. I’m collaborating with the Margaret Jenkins Dance Company, creating video set for a new piece – Light Moves. Paul Dresher is composing the music, and Michael Palmer is doing text. It will premiere at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts on November 3rd.

We did a preview last October, just to try and see what some of the video looks like with the dance on a stage. It was really interesting, and my assistant took some still photos of the performance. Then I left for a few months to work elsewhere and found myself looking at these stills and getting really excited about the intense emotional charge, the relationships of the movements of the dancers, their facial expressions which you don’t really see during a performance but in the stills they were caught and they just imbued it with all this charge.

The best is when I begin a painting from something that’s charged, but what creates that varies over time. Sometimes it’s nature, sometimes it’s urban, sometimes it’s poetry, sometimes it’s music, sometimes it’s the season or a place I’m visiting. So, these are all the different ways I start.

Z: The exhibit at Modernism is titled “Multiverse Part I.” Is there a “Multiverse Part II” in the works?

NK: Yes. That’s also going to open in November, and that show will be all hybrid paintings. Hybrid paintings are paintings on which I project video. The video interacts with the paint in a way that is somewhat mysterious because you see both media simultaneously and it’s hard to tell which is which, except when there’s movement. The hybrid paintings are meant to be viewed with enough light to see the paint as well, the point being that there is an unexpected but very seductive interaction between the movement and the stillness.

A couple of years ago at my last show at Modernism, I showed paintings in the front room and hybrid paintings in the back room. This time we decided to separate the two parts into two shows. So this part is paintings and the next part will be hybrids.

Z: I’m curious about how you began working with the hybrid paintings and about your interest in the digital and video parts of your work, both in that previous show at Modernism and in the Shtetl installation at the Magnes Museum, among others. Does video open up new avenues for expression with paint?

NK: Well I think that different media inform each other and also create new thought patterns and new ways of seeing. I really enjoy both media. In some ways they couldn’t be more different. Definitely through working on video I’ve come to see paint differently, and certainly the way I paint has informed the way I work with video, which is always very multi-layered, a lot like the way that I build paint.

Z: Several of the paintings in this show at Modernism evoked Giverny. How has Monet influenced your work?

NK: Monet is definitely one of the influences, definitely. I studied art history — I got a master’s in art history — and, as I started to paint, art history was very much on my mind. I thought a lot about how painting has changed, and I won’t use the word “evolved” because I don’t think it’s actually an evolution — it’s just a following of different strains and different possibilities. The way I like to think about it is that they all still coexist, you know, all those possibilities. It’s not like some ways of painting are outmoded or are no longer interesting. I think it’s all about the mash-up, and how it all comes together in new ways all the time.

Z: Several years ago one reviewer wrote that in the past you’ve used your paintings as studies for your drawings. Was that the case then, and is it still the case now? How do the two kinds of work inform each other?

NK: Well, they are parallel paths and they definitely inform each other. But I don’t make a drawing in order to make a painting — although I’m going to amend that in a moment! But I have several times, after the fact, become interested in looking at the structure of a painting without its color. I’m interested in what my eye follows as the motion, the armature, and that becomes much more apparent in black and white. And of course, making a drawing of one of my paintings forces choices about what to extract, or abstract. There’s a lot of line in my work and I’m very connected to what line does and how directly it expresses the impulse and the thought.

Z: That makes sense, because it’s evident how much care you take with the lines and with the layers of lines and the underlying architecture in all the paintings, which is part of what makes them so compelling and interesting.

NK: Thank you. So, just to go back to the point that I was going to enlarge on: When I said that paintings don’t come from drawings, in fact they did come from drawings when I first started, when I was in graduate school and was trying to figure out how to work. At one point I stopped painting altogether and just drew, to try to figure out what it is that I wanted to do, what my work was about and how to work. I found it much easier to arrive at [answers to those questions] through drawing, through mark-making, in fact. I did that exclusively for about a year, and then just as I was finishing my MFA I realized that now that I had found my world, I wanted to paint it. So, in a certain way those first paintings did come from the drawings before them.

Z: When you started working, did you know what you wanted to draw? Did you have a sense of where you wanted to go with the work?

NK: Well, what I wanted to draw was a world, meaning that you wanted to enter it, it made you enter it, it was compelling, it was complete, and it was very detailed, the way the world is very detailed. Even emptiness is detailed, is how I see it.

Z: You have studios here in Oakland and in Paris, studied in New York and England, were born in Israel. I’m sure all those experiences have informed your work. What about the West Coast? Is there anything about the West Coast specifically that inspired your work in a particular kind of way? Has being here shaped you?

NK: I know that it has. But maybe I’m so “in it” it’s a little hard to see how. Certainly the awareness of geography has affected me, the extraordinary landscape – desert and ocean, which connect me to my early years in Israel. Lush vegetation, with its obsessiveness. Also physical proximity with Asia (as compared to Brooklyn, where I grew up). I feel that somehow enters into the atmosphere of the worlds that I’m creating. But also philosophically, the concept of simultaneity, and also the importance of calligraphy. And, I love a lot of the West Coast artists. David Parks was an early influence, as was William Wiley.

Z: Are you aware of Michal Rovner, and, if so, what do you think of her work?

NK: I actually know her personally, and I very much like her work. Her sensibility is consistent in many media. I loved her room-sized installation at the Whitney a few years ago, but also her smaller sculpture – the way she mixes video and physical objects. It’s something I’ve done a little bit of, and would like to explore more. A couple of years ago I made a piece called “Dictionary”; I wrote a text about my father’s relationship to a dictionary, and projected it on an open dictionary. It was in a show at Knoedler Gallery, and then at the Jewish Museum in New York in 2009. I’m not sure if seeing her work planted that seed, but perhaps!

Z: You’ve done a number of pieces that involve words in the drawings and in the paintings, including some of those that appeared in ZYZZYVA in 1996, and in the show at Modernism now. (“Poetic License,” for example). These pieces are especially striking. What do you think is or can be the effect of using words in the painting?

NK: I love the way William Wiley uses words in paintings. Words are like the “atmosphere” in his work – like air molecules. The danger is that they can become captions or one-liners.

I never want to use words in a way that closes down meaning. I think of paint as a language. And words are, of course, language as well. I like to expand the number of languages I can combine in a painting. I also like to write backwards – which, strangely, I find much easier than reading backwards.

When I started using language in the paintings in the early ’90s I discovered that I didn’t want to commit to a particular text, the way Cy Twombly does, for example. I think he’s a master at conveying parallel sets of information that don’t interfere with each other, or close each other off. But what I’ve discovered works for me is to refer to language, to play with the building blocks of language — letters and letter-forms, and occasional words, often indecipherable. I know several alphabets, and sometimes invent imaginary ones. These are also ways to introduce sound into the experience of looking at a painting, without pinning it to a meaning.

Z: Is there anything you’re been reading lately that you find inspirational or exciting?

NK: Right at the moment I’m reading Keith Richards’ biography, “Life.”… It’s fascinating. It’s making me listen to the Stones’ music with new attention. He writes about trying to find different ways to make sound by breaking rules — unusual guitar tunings, technical stuff like that. I identify with that in the way I work with video. Technology is designed by people who envision a certain use for it. Well, I like to invent other uses.

In the last year, a couple of the standouts were “Cutting for Stone” by Abraham Verghese, “Freedom” by Jonathan Franzen, though I don’t love everything he’s written.

Z: What do you find especially exciting on the West Coast Arts scene right now?

NK: I’m interested in the whole Mission arts scene – it’s nice to be able to see work by artists new to the world of showing, as well. I like the melding of graffiti and “fine art” … the way that’s evolving on the West Coast. But also I find “Outsider Art” fascinating. I became more familiar with it through Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, which had a Parisian Branch [Galerie Impaire] for a few years, where I showed in 2009 with Donald Mitchell, one of their internationally known artists. I recognize that obsession and obsessiveness in my vocabulary, my method, even.