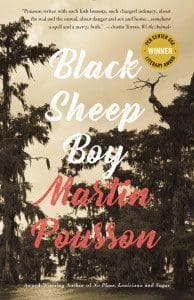

Author and poet Martin Pousson’s Black Sheep Boy (182 pages; Rare Bird Books ), winner of the 2017 PEN Center USA Award for Fiction, and re-issued in paperback last month, is an unforgettable novel with prose that reads as both brutally honest and hypnotic. The story centers around our narrator, Boo, as he struggles with growing up gay in Acadiana, the bayou lands of Louisiana. Told over the course of sixteen linked stories, the book covers a wide span of time, from the “wild-hearted” boy’s birth to his freshman year of college, and centers around the qualities that make him the “black sheep” of the title.

Author and poet Martin Pousson’s Black Sheep Boy (182 pages; Rare Bird Books ), winner of the 2017 PEN Center USA Award for Fiction, and re-issued in paperback last month, is an unforgettable novel with prose that reads as both brutally honest and hypnotic. The story centers around our narrator, Boo, as he struggles with growing up gay in Acadiana, the bayou lands of Louisiana. Told over the course of sixteen linked stories, the book covers a wide span of time, from the “wild-hearted” boy’s birth to his freshman year of college, and centers around the qualities that make him the “black sheep” of the title.

Boo is unable to fit the masculine identity that his family, religion, and community demand of him. During childhood, his manner of movement and speech convinces his superstitious and abusive mother he is possessed by the devil: “Mama strapped down my restless hands with duct tape then ordered a doctor to fit braces on my twisting feet. By five, I’d learned sacrifice for the stutters when another doctor cut out a flap of flesh to correct my tangling speech. Mama showed me the horn-shaped piece to prove a point: the devil had me by the tongue.” His father, meanwhile, is mostly absent as he works from sunrise to sunset to meet his wife’s ever increasing demands for a piece of the good life she feels she deserves.

Boo is called Sissy, Queen, Fairy, and Jenny-Woman as he encounters drag-queens, priests, and neighborhood bullies. He has a variety of sexual encounters; some sweet and gentle, others haunting and traumatizing.

Pousson’s writing is melodic, with phrases that slope and sweep along the page. It is easy to get lost in the cadence and diction of his beautiful language. His phrasing is surreal and poetic; in one of the strongest stories, Boo remembers his grandfather—who by this time has lost all speech— and imagines him as a shapeshifting werewolf, proud of his grandson: “His eyes are black as bayous… From his neck, an endless chain of zigzag teeth swing like a second jaw. He moves without caution and knows no taboo. He’d frighten any tataille into the woods, chase any pack of animals into the dark. He’d terrify the words out of any boys mouth, chew the mask off any villains face. Yet his breath is perfume.”

At times the writing is so fantastical that it is difficult to find a more grounded, emotional connection to the storytelling, but that does not take away from the power of these stories. Pousson wastes no word. Black Sheep Boy represents an entertaining and dazzling read, and serves as a heartfelt ode to those the author addresses in his dedication: the “odd ducks, strange birds, and queer fish” among us.