On October 3, 1957, a judge ruled that Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems was not obscene. It was a decision that would pave the way for publication of works from Henry Miller, D.H. Lawrence, William Burroughs, and others. A key figure from the Howl trial was Shig Murao. His life and legacy has been documented in a website that launches today, www.shigmurao.org. This essay is adapted from a much longer biography with multiple supporting documents published on the website created by Richard Reynolds, a longtime friend of Murao’s.

Shig Murao was the clerk who on June 3, 1957, was arrested and jailed for selling an “obscene and indecent” book—Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems—to two undercover San Francisco cops at the City Lights Pocket Book Store. City Lights publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti was subsequently booked and charged with publishing the book. While Shig is primarily remembered as the clerk who was arrested for selling Howl, he was much more than that. He managed City Lights for its first 22 years and crafted the unique atmosphere that made the legendary San Francisco bookstore into the institution it remains today.

Even so, Shig is in danger of being written out of the history of City Lights and of the San Francisco Beat era, too. (For instance, in the 2010 film about the obscenity trial resulting from the arrest, Shig was nowhere to be seen, even though he and Ferlinghetti were co-defendants and sat next to each other throughout the proceedings.) He was a close, life-long friend of Allen Ginsberg’s until the poet’s death in 1998. Whenever Ginsberg came to San Francisco, he would stay in Shig’s Grant Avenue apartment. And no one who frequented City Lights in the early years could miss Shig. When you walked into the store he would be on your left, a Coke can in hand, sitting on a high stool behind the book-piled counter. If he didn’t like you or suspected you had an agenda, he could be coldly dismissive. But once he knew and accepted you, he was warm, charming, and very funny.

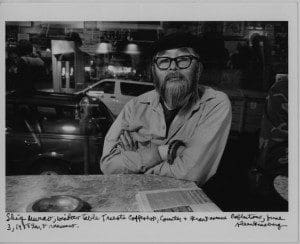

Born Shigeyoshi Murao in 1926, he was universally known as Shig. His playful demeanor—not to mention his signature beard, Pendleton shirts, Royal Air Force exercise vest, horn rimmed glasses, and bowler—rendered him unforgettable. He was the black sheep of a very traditional samurai family that lost its Seattle butcher shop after Pearl Harbor and was interned during World War II. (Shig joined the U.S. Army in 1945 and served as a translator in occupied post-war Japan.)

Shig arrived in San Francisco in the early Fifties, and when Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter Martin opened the City Lights Pocket Book Shop in June 1953, they hired him as a clerk, paying him in books for the first couple of months.

Poet Kaye McDonough tells the story of the night a couple of immigration agents came to City Lights looking for an English guy who hung out there. Shig told them he didn’t know the guy. The agents then turned their attention to him and warned him that if he didn’t cooperate they would send him “back were you came from.”

“Okay, okay,” he said. “Send me back to Seattle.”

For more than two decades, Shig presided over the bookstore as Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Michael McClure, and an ever-changing cast of poets, writers, musicians, comedians, and North Beach characters congregated there—each adding a different timbre to the bebop suite Shig orchestrated in the triangular structure that houses the bookstore to this day.

In 1975, Shig suffered a stroke, and when he returned to work later, Ferlinghetti told him he wanted to make a change that would keep Shig as book buyer and manager but put a “businessman” above him. Shig was a proud man. He refused to accept what he saw as a demotion, and never spoke to Ferlinghetti again. (And, indeed, it seems clear that Shig and a “businessman” would have come to loggerheads within minutes.) The split was wrenching for both Shig and Ferlinghetti.

After he left City Lights, Shig held court in the Caffe Trieste, a block from the bookstore. As therapy for the stroke, and to provide an outlet for his creative temperament, he took up the shakuhatchi, a Japanese bamboo flute, and shodo, Japanese calligraphy, and moved on with his life.

But a second stroke in 1983 left him unable to pursue his new passions. Undaunted, Shig found another way to express his artistic bent. He resurrected Shig’s Review, a journal he first published in 1960, which he was now publishing as a zine.

He would select a small collection of poems, photos, woodcuts, letters, or previously published articles, type the copy, and take the edition to a local copy shop to print 20 or 30 copies. The final touch was Shig’s hanko—a character used as a signature in Japan—stamped in red ink on the front page. (Some issues also included a “Shigspeer Press” rubber stamp logo.)

When he finished each issue of Shig’s Review, he would put a supply into a shoulder bag, walk down to the Trieste, and give them to people he liked. There was no pretense in these offerings; Shig saw them as gohobi, a small gift or prize. He would publish about 80 issues of the quirky review before his death.

In 1998, while visiting the Stanford Library in his electric wheelchair, he mistook a cement stairway near the library for the adjacent wheelchair ramp and piloted the wheelchair right over the stairs, catapulting himself to the pavement below and breaking his hip. He spent his final months in the Pleasant View Convalescent Home in Cupertino, California.

When I visited Shig there he seemed lucid at first, asking about my wife and questioning me about whether the Chinese restaurants he favored had raised their prices. But then he told me that he sat outside most days because he was waiting for the flying saucer that would take him home to Seattle.

The “saucer” arrived on October 18, 1999, carrying Shig away. He didn’t leave the kind of literary legacy Ferlinghetti is known for. But in his quiet way he played a pivotal role in creating the charged aura that marked City Lights and the Beat scene that grew up around it.

Richard Reynolds recently retired as communications director of Mother Jones magazine. His writing has been published in the New York Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Salon, Saveur, Gourmet, and other publications.

What a wonderful tribute — masterfully delivered and something that I could not stop reading through (very rare for me and any LED screen!). Thanks for putting this out there!

A wonderfully nostalgic revisit to my late adolescent excursions to the City Lights of the 1950s and to finally learn something about that Asian guy always behind the counter.

It’s truly a great and useful piece of information. I am happy that you shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

In my early 20’s, I lived in the Rex Hotel for $7.00 a week for a time, and ate at Mike’s Pool Hall and hung around City Lights. I, like so many, loved to chat it up with Shig, and one time he invited me to drive down to Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s home in Big Sur and we spent the night in hammocks, me on the top bunk. Shig snored all night and a dim light was on, so I got zero winks of sleep. I was so young, and had not yet found my voice, so neither Shig nor Lawrence knew I was exhausted. I politely listened to these two great men, hit the hay, chatted in the morning, and drove back to North Beach. Rest In Peace, Shig. I loved reading this beautiful tribute about you.