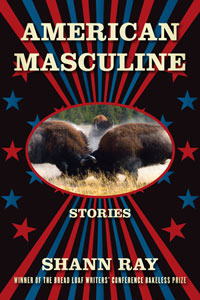

Shann Ray is a writer, researcher, and professor whose first collection of stories, American Masculine (Graywolf Press; 192 pages), won the 2010 Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference Bakeless Prize.

Almost all of the collection’s stories take the dramatic Montana landscape as their backdrop, and almost all of the stories deal with men struggling to make sense of such perennial themes as death, infidelity, addiction, and abusive fathers. Ray, who lives in Spokane, Washington, with his wife and three daughters, writes with an unflinching honesty, and his work remains empathetic and lyrical regardless of the subject, be it the expansive Montana sky or the brutal anguish of a broken man.

The following interview with Ray was conducted via email.

ZYZZYVA: You teach “leadership and forgiveness studies” at Gonzaga University. Can you explain what that is?

Ray: I teach in a doctoral program in leadership where scholars from the U.S. and around the world gather to encounter what the Jesuits call the Magis, the idea that among many good things the ultimate good must be discerned and acted upon, and that cura personalis, or education of the whole person (heart, mind, and spirit), informs the interior life of all humanity. Leadership is the study of personal, organizational, and global influence.

My own research is in leadership and forgiveness studies, a nexus where the personal and the global meet (see Forgiveness and Power in the Age of Atrocity, my forthcoming book from Rowman & Littlefield). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa comes to mind, as well as People Power I and II in the Philippines, the reconciliation ceremonies at the site of the Big Hole Massacre in northwest Montana, and the work of people like bell hooks, Paulo Freire, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Common research findings in forgiveness studies today show people with higher forgiveness capacity experience less depression, less anxiety, less heart disease, greater emotional well-being, and the potential for a stronger immune system. The great poet Kahlil Gibran echoed this sentiment by saying “the strong of soul forgive.” A very courageous statement by him, especially when you consider the gravity of the losses we encounter in his book The Broken Wings.

Z: In American Masculine’s foreword, Robert Boswell states that some might label your writing “experimental.” If so, is your experimentation a conscious decision?

Ray: I do see some of my stories as experimental, and at the same time carried in the hands of classic narrative realism. The experimentation is conscious for me and serves as form serves in poetry. There is an elegant resistance form gives to a poem, and I try to find forms for the short story that result in that same sense of elegant resistance.

Z: In almost all your stories, there is a contrast between the vastness of Montana’s landscape and the “smallness” of the characters (their private tragedies, for example, and their small towns and cramped trailers). Did you have some intent behind this contrast?

Ray: I’m reminded of Mary Oliver’s radiant question, “What is it you want to do with your one wild and precious life?” and her openhearted answer is, “When it’s over I want to say all my life I was a bride married to amazement, I was the bridegroom taking the world into my arms.”

The vastness of the wilderness in Montana and throughout the world finds an equally profound imprint in the vastness of the human heart. There is intimacy in the wilderness, and danger, just as there is intimacy and danger in our small towns, our cramped trailers, our homes, our sprawling cities. Are the invisible cities of Italo Calvino actually women and men and cultures? I believe such cities are the loveliest cities we know.

Z: Some of these stories open with a tragedy — a death or a car crash, for example — and then travel back to the tragedy’s origins. How do you think this somewhat unorthodox structure aids a story?

Ray: I hadn’t directly thought about it in the initial composition of the stories. I like your vision of this, and now that I look again I see a kind of spiraling pull from the externals of our personal lives down into the heart of life. For me there is a natural desire in people to love and be loved. Tragedy is love’s very close sister or brother. In tragedy we can be completely undone. Inconsolable. Even to the point of death. In love we sometimes receive the grace to be lifted and put back together more beautiful than before.

Z: What about the experience of grief interests you as a writer?

Ray: I see grief as a beloved other whose voice we ignore to our own peril. In fact, I love the image of drawing grief closer in, again drawing it close as you would a good brother or sister and listening to what it whispers in your ear. The immensity of the losses we face is very difficult for me to understand in light of the concept of a Divine presence. Yet persistently, in terrible hurts that range from cultural genocides to the atrocities that occur in the life of the family, people open my soul again and again with the clarity and beauty of their voice. Here the Divine in them and in the world is affirmed.

Often when I return home from working with families and trying to help them face the great darknesses they inevitably must face, one of my daughters will ask me, “Did you cry today?” The tender and fierce and gorgeous heart of that simple question overturns the tenacious hold of atrocity in the world.

Z: What is the state of American masculinity?

Ray: One could say an extreme mediocrity exists in much of American masculinity today, characterized by emptiness, impoverished relational capacity, an overblown or under-developed sense of self, and a life with others that is often devoid of meaning. Such men are filled of things like excess television, excess debt, excess video games, excess sexual focus, emotional shallowness, and the man’s agenda at the expense of others. Again, no words for feelings. Violence. Privilege for privilege’s sake, which results in decadence, and in the end decay, and finally death.

The Western world, which in bell hooks’ terminology, is inherently white, supremacist, and patriarchal, is currently experiencing this decadence, decay, and death. The great psychologist of the 20th century, Carl Jung, gave a clear and also fear-invoking expression of the masculine and the feminine. In Jung’s conception the masculine is symbolized by the logos, which he referred to as the power to make meaning, to be meaningful, and to be experienced as meaningful by loved ones and by the collective humanity around us. Not the super-rational Western man, incapable of emotion and in fact regret, but a man who lives deeply, loves well, and is well loved. A question then rises, how many men do you know who are experienced as meaningful in their relationships with women, with their children, with others?

The Western world, which in bell hooks’ terminology, is inherently white, supremacist, and patriarchal, is currently experiencing this decadence, decay, and death. The great psychologist of the 20th century, Carl Jung, gave a clear and also fear-invoking expression of the masculine and the feminine. In Jung’s conception the masculine is symbolized by the logos, which he referred to as the power to make meaning, to be meaningful, and to be experienced as meaningful by loved ones and by the collective humanity around us. Not the super-rational Western man, incapable of emotion and in fact regret, but a man who lives deeply, loves well, and is well loved. A question then rises, how many men do you know who are experienced as meaningful in their relationships with women, with their children, with others?

I think we can branch Jung’s typology out and encounter some of the current complexities that exist in human relations by noticing that all of us have both masculine and feminine within us, and the extent to which we hide or subdue either of these, we suffer. Jung himself pointed out this tenacious aspect of human fallibility, that when we deny our faults, we are consumed by shadow. When we are consumed by shadow we in effect project our shadow onto the world with harmful results — we refuse to take responsibility for life and in fact block others rather than inviting them to help us change and become more whole. To be more whole is to be more capable of honoring the feminine and the masculine in ourselves. In order to heal our fear of our own shadow, and heal our inability to love and serve life deeply and well, we must have two things: insight and good will. In the language of family, we need understanding and love. Understanding and love remain the most significant forms of power in the known world.

America has many beautiful and soulful men who understand and embody a great balance of love and power. I believe the true test of legitimate power is one given by Robert Greenleaf, a former executive at AT&T, a Quaker, and something of a philosopher poet who was a contemporary of E.B. White and Robert Frost. For Greenleaf the true test of power is that others around you become more wise, more healthy, more free, more autonomous, and better able themselves to serve others and the world. I’ve found beautiful, soulful, powerful men in every country I’ve had the blessing to work in, countries that range from Africa to Asia, and from Europe to South America. Often these men have emerged from a profound crucible of forgiveness. They live with deep responsibility to others, and do so even in the wake of terrible losses.

Z: Can you talk about the moving, epic of a short story “The Great Divide” from American Masucline? How did it come about?

Ray: That story was taken by McSweeney’s after a two-year draught, reminding me again of how silent and songlike and contemplative and prayerful the writing life is. I wanted to craft a story that would show love and respect for the very grand and ominous landscapes of Montana and also show love and respect for the women and men and families of Montana, Native American and white, and profoundly diverse in the interior life and the life of the collective. There has long been a philosophy that the world, the landscape, and people grind you up and spit you out, so you better be ready or your head might get taken off. The mountains kill you. The animals kill you. Your family kills you. Life kills you. This seems immanently self-focused to me. I’ve felt deeply loved by the mountains and rivers and skies of Montana, for example. How about the counter philosophy that there exists an abiding intimacy in the world, despite and even within the presence of evil and death? “The Great Divide” does not ignore or forego or turn a blind eye to the presence of human evil. The story reaches for light in the presence of this evil.

This notion of an abiding intimacy, championed by Holocaust survivor and leading European psychiatrist Victor Frankl, and many others, suggests something I find to be much more believable: personal responsibility and collective responsibility are not only present in the world but paramount. How much faith does it take to believe everything is out to get you and annihilation is the essence of existence? I think it takes a great deal more faith to convince myself death is the only way than it does to open my eyes to the inviolable dignity of others, the environment, and life itself. The experience of love, like the experience of a smile, achieves almost immediate affirmation of the existence of something more. Frankl, quoting the poet Anton Wildgans, said, “What is to give light must endure burning.” He said this even after he had lost his parents and his wife and his brother in the fires of Auschwitz, Theresienstadt, and Bergen-Belsen. In the face of such wanton evil Frankl had the gall to say this: “The salvation of [humanity] is through love and in love. I understood how a [person] who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for a brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved.”

Frankl also echoed the basic intimacy of our biology when he said:

“Consider the eye. The eye, too, is self-transcendent in a way. The moment it perceives something of itself, its function — to perceive the surrounding world visually — has deteriorated. If it is afflicted with a cataract, it may ‘perceive’ its own cataract as a cloud; and if it is suffering from glaucoma, it might ‘see’ its own glaucoma as a rainbow halo around lights. Normally, however, the eye doesn’t see anything of itself.

“To be human is to strive for something outside of oneself. I use the term “self-transcendence” to describe this quality behind the will to meaning, the grasping for something or someone outside oneself. Like the eye, we are made to turn outward toward another human being to whom we can love and give ourselves.

“Only in such a way do people demonstrate themselves to be truly human. Only when in service of another does a person truly know his or her humanity.”