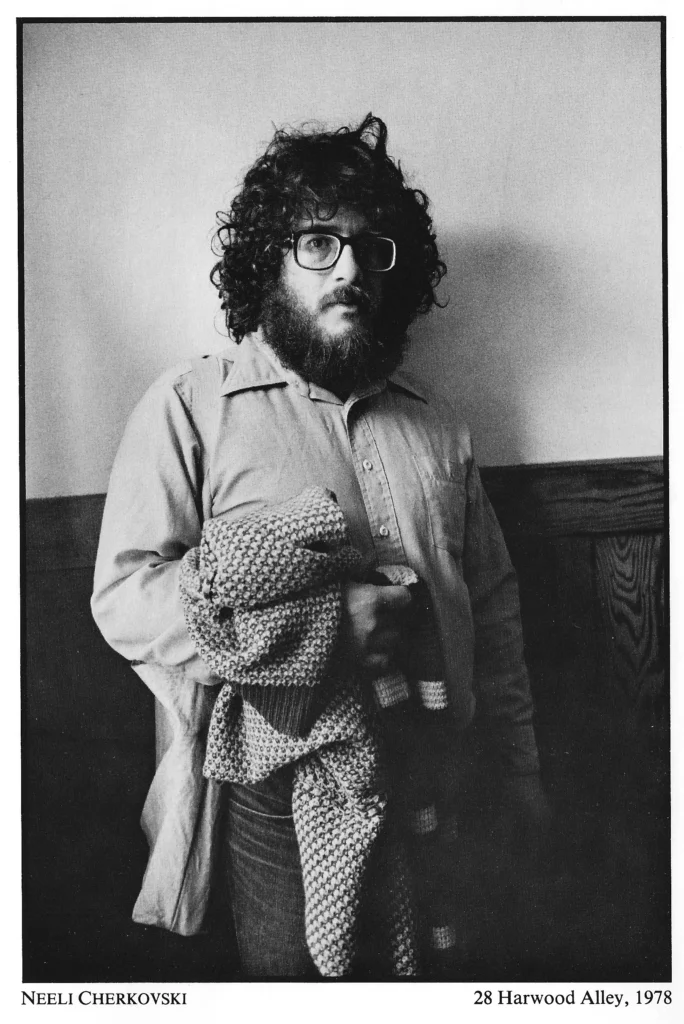

Neeli Cherkovski was that rare figure who both chronicled a vibrant literary culture and contributed to its flourishment. Cherkovski, who died on March 19 at age 78, was a Zelig of sorts, long at the center of the literary scenes of San Francisco and Los Angeles; he wrote biographies of Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Charles Bukowski, co-edited a Los Angeles literary magazine (Laugh Literary and Man the Humping Guns), founded the San Francisco Poetry Festival, and wrote poetry collections (Animal, Elegy for Bob Kaufman and Leaning Against Time). A native of Southern California, Cherkovski had made San Francisco his home for the past half century. A frequent presence at City Lights Bookstore, he was to have been celebrated at the store on May 20 for his forthcoming collection, Selected Poems 1959-2022. (City Lights says it hopes to host a tribute to Cherkovski in the near future.)

Cherkovski also contributed to ZYZZYVA. The journal published a selection of his writing in Issue No. 15, in 1988. The piece below is from Whitman’s Wild Children, an anecdotal/critical account of ten American poets (in this selection he writes of Harold Norse, while mentioning Charles Bukowski and Philip Lamantia) that was published by the now-defunct Lapis Press of San Francisco. “I have given myself over to language,” Cherkovski writes. Giving himself over to language—that he did over the course of a lifetime devoted to words.

In the Penguin Modern Poets series there is a formidable threesome gathered: Bukowski, Lamantia, Norse. That book had been conceived not long before I met Norse at Bukowski’s. One of Norse’s best poems in that collection is a tribute to William Carlos Williams, in which he thanks the elder poet and mentor “for the pink locust / & the white mule/ for the precise eyeglasses/ & the scalpel/ that sliced memorable plums.” It is a poem I know Williams would have liked, written as it is in the language we speak every day. That is the language Norse illuminates, both at home and abroad:

the beast cannot follow the waterbearer / into the upper chambers / & the time / is at hand

I met Norse after I had been in Delphi. That is, I really came to terms with who this man is and who I am and what we could each become after Delphi, long after Bukowski, 500 miles north of Los Angeles. I remember when Gregory Corso called Norse from my telephone and said: “Harold, this is Gregory. I lost my fame. I don’t know what to do. Allen and Bill … they still got it. But me, I lost it. Even Kerouac still has it, dead as he is. But now you have it too. What am I gonna do? Oh, poor Gregory.” Five minutes after his call, Harold phoned to tell me, “Gregory called. He told me he lost his fame. It’s terrible. He said I was more famous than he is.”

Poets play with each other. Vanity pursues them all, stalking us even beyond the threshold of our inner landscapes, wreaking havoc with the flora and fauna within. Even Gregory, the still-mop-haired beatnik poet, suffers from it, maybe most of all in his never-ending three-ring circus of enfant terrible. And Norse continued: “I really didn’t know what to say to Gregory.”

“Help him find his fame again. It must be somewhere,” I wanted to answer.

Norse is famous in his own eyes. He has confidence. Because of that fact alone, his output has been incredible and is rich in form and texture. I am glad I met him. I’m glad Bukowski and I were so excited back in the sixties over the expatriate who was coming to live in Venice, not far from where we both lived. Bukowski would read Norse’s work and I would listen, and then it was my turn. “Pretty damn good, right?” Bukowski would say. “You got it, Hank,” I’d answer.

I am approaching Delphi as I sit in my second-floor workroom overlooking Andover Street and Diamond Heights. Dark gypsy eyes stare at me as I pass quickly by, totally occupied with the idea of being the poem. No more will I argue over the merits of the Whitmanic self flinging arms and legs over a cliff of pages or attempt to explain the stanzas forever oozing from the fingertips of Gertrude Stein. Pure man, pure language, pure water falling into the Aegean. I am with the poem. I am of it. I have given myself over to language. With what searching mannerism will I finally nod my head in approval or disapproval? None. No head shaking is needed. I am making my way into the poem. I call this poem “Delphi.” Trees are aflame, the sky is bright orange, and a lizard darts quickly under a rock filled with the soul of the earth.

l am the waterbearer. I am climbing that hot, dusty road from Thebes to Delphi. Dark gypsy eyes follow. “Tell me, is this the way to the word?” I ask an old man who hobbles by. His eyes are ashes and his tongue is a lizard crawling under a rock. Oh, the poem. It provokes me. I hear it amidst “the hollyhocks in the olive grove…” and I know that the time is at hand. I see that the word is here, now, with me, and always has been. I, the poet and scribbler, am grabbing the word. I am greedy. I don’t want to be, but I am. After all, I’m only flesh and, as Corso says, “we’re nothing but hairy bags of water.”

Here is Delphi, finally, teetering on the side of a rocky mountain, as if it were going to slide right into the canal below. I wrote a long poem in a French notebook, mixing fire, water, earth, and air. Somewhere between Piracus harbor and the gates of Jerusalem I lost it. Only one other poet, Kush, who lives in San Francisco, saw it. What a poem that was. I really had it down. I would have wanted Harold Norse to see it. That is one cupful of elements I would have passed his way. I would have said, “I wrote this in Delphi after reading your poem ‘Addio.’ It was late at night and the heat pressed in on me, unbearably. A Canadian kid slept across from me, his legs dangling over the bed. In the morning, he was a lizard with huge Delphian eyes, glaring.”

There goes Delphi. Here comes the poem. Goodbye to dreams of taming the evil inclination. Norse said it years ago, and now I know: “Throw caution to the wind.” Good advice, easily as welcome as Henry Miller’s dictum to burn the books and start over again. The impenetrable continents are opening. We have wings. We can fly there. The word is waiting. The word is above us and below. From Norse to me to an immense emptiness … and a song.