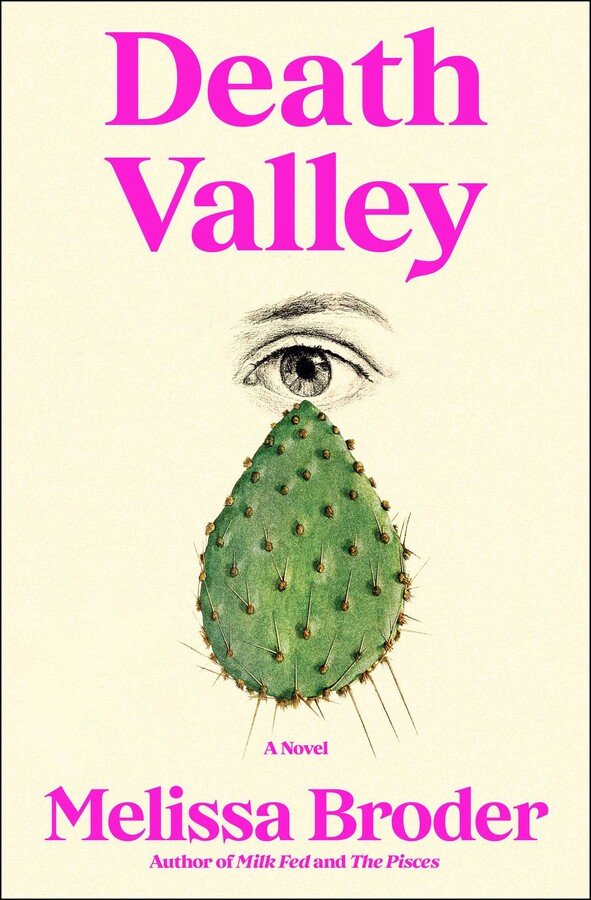

Melissa Broder’s new novel, Death Valley (Scribner; 240 pages), begins with its unnamed protagonist peeing—and trying to meditate—in a Circle K bathroom during a getaway to Joshua Tree. This bodily moment will pair resoundingly well with another sort of release at the close of this short book of blood and guts.

Broder’s protagonist, we learn, is a novelist working on a book about a young-to-middled-aged woman, a pseudo-hippie, struggling with her husband’s chronic, undiagnosable illness. The writer is sober after years of alcoholism, depression, and suffering from the long-term hospitalization of her dying father. She’s seeking spiritual solace on a toilet because everything seems to be falling apart around her.

Death Valley’s opening scene is emblematic of what Broder does best: melodrama, the breakdown of self, of family ties, the loss of comfort—and, yes, bodily fluids. In Broder’s previous two novels, The Pisces and Milk Fed, the protagonists turned breakdown into breakthrough with sex (merman coitus and the like). In Death Valley, the stakes are raised substantially: our protagonist must greet death through desert travails to achieve any emotional resolution.

Before we arrive at the end of this journey through California’s terribly hot and cold terrain, there is a whole lot of incidental material to read through: information about secondary family members, plant and sexual preferences, and the nitty-gritty details of men’s physical afflictions. It’s all slightly forced, and this is most true in the case of the protagonist’s husband. So many recollections, as well as a plot-propelling verbal conflict between the couple, leave much to be desired. The husband’s undiagnosed illness extends to his personality. His recurring sigh—the most frustratingly uncommunicative way to signal feelings—could not be more apt. This flatness can be forgiven, though, as the meat of the novel lies in the daddy issues. Dad is quiet, maybe mentally ill, and dying. When the protagonist faces mortality in the desert and envisions her father at all life stages, a deep understanding of attachment, loss, and ancestry blossoms. But when the scenes of his medical agony are alternated with the writer’s unfolding life-or-death struggle, one wishes we could stay with our quixotic lead and her comic observations on, say, crotches and online perusing of sweats.

Broder is good at incorporating fantastical elements (nipples with reserves of Dr. Pepper, an extraordinary cactus, cranky geological formations) without dipping into the realm of sci-fi. No reasons are given for such wild creations, but none are needed. By contrast, the relationships with male characters lack pizazz; if only the protagonist’s connection to her husband and father were written with the same special touch of ridiculousness that the magical cacti and birds and rabbits hold.