The author Herbert Gold died on November 19, at the age of 99, and it’s still hard to believe that somebody so kinetic, so sonorous, could be gone from San Francisco, his longtime home.

It wasn’t unusual to drive up Van Ness Avenue or navigate traffic somewhere in the Mission and see Herb, already in his late 70s, ambling along the sidewalk, dressed in a light jacket and comfortable shoes. He loved to walk, for the exercise, I suppose, but also because he always considered our city an urban village. And how does one appreciate living in such a village if they’re not on foot, seeing what there is to see?

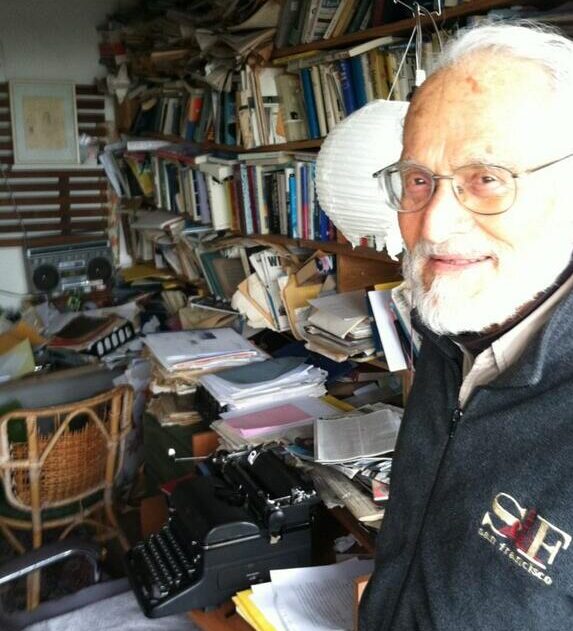

His apartment—the apotheosis of bohemian living (and, I suspect, of having rent-controlled housing and a thoughtful landlord)—had dramatic, stomach-clenching views of downtown and beyond. (My fear of heights, no doubt, had something to do with the impression the vistas from his front room made on me.) His place was crowded with books and papers and all manner of art, especially from Haiti, a place Herb wrote about extensively; in fact, one night in North Beach, a small group of us sat in an art gallery to watch a French documentary about Herb and his deep affinity for the place. His apartment was only reachable by a flight or two of steps. So maybe all the walking served another purpose: keeping Herb in shape so he could come and go from his home as he pleased.

Herb had all sorts of stories about publishing from the days when Norman Mailer and Philip Roth were the rage, and, in general, seemed to have known everybody worth knowing. But Herb was a great talent, too—as you can see in his story “Melinda, Doing Her Best,” which ran in ZYZZYVA Issue 93 in 2011—and so of course he would have been moving in those rarefied circles of clinking highball glasses and veils of cigarette smoke.

“Let me tell you a story, Oscar, about Norman Mailer,” he said to me at one of our all-too-infrequent lunches. Herb had been at a party, talking to somebody, when he felt the stare of Mailer upon him. Herb asked him if there was a problem, but Mailer said nothing and kept fuming. If you’ve seen pictures of the young Herbert Gold, and compare them to photos of the young Norman Mailer, and then consider the unbridled and toxic machismo of the time, not to mention all that drinking, it would be fair to speculate that Herb was talking up a young woman in such a way that made Mailer feel, let us say, insecure. At some point, Mailer’s scowl found a voice and, as Herb related it, called him out. “That’s it! You and me, Gold. Outside!” It was snowing, and they were several floors above a street in New York City. But Herb, after asking Mailer if he was sure about this, obliged, the two of them taking the time to put back on all their winter clothes before trudging downstairs.

When they finally got outside, Herb said, Mailer squared up and looked him straight in the face. What Herb didn’t say, but I already knew, was that he had enlisted in the Army around the time of World War II, so it wasn’t as if he couldn’t handle himself. And it’s quite possible that given Herb’s suave demeanor that Mailer forgot that he knew that about Herb, too. Herb waited for Mailer to do something, until, finally, Mailer happily bellowed, “You’re all right, Gold! You’re all right!” There was some backslapping and up they returned to the party.

No question. Herb was all right.

Oscar Villalon is the editor of ZYZZYVA.