“Literature, as I saw it then, was a vast open range, my equivalent of a cowboy’s dream.’’ So wrote Larry McMurtry about how life at his father’s Idiot Ridge cattle ranch changed forever when a World War II-bound cousin dropped off a farewell gift of a box of books.

Riding that range for decades since, McMurtry has been condescended to, by the usual contingent of Eastern critics, and overpraised, for his Pulitzer Prize-winning epic, Lonesome Dove, which he self-mockingly described as the “Gone With the Wind of the West.’’ But the bulk of his work, including the Thalia trilogy (Horseman, Pass By; Leaving Cheyenne; and The Last Picture Show) and the Houston series (Moving On, All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers, Terms of Endearment, and Somebody’s Darling) is chiefly remembered for the film adaptations they spurred.

Tracy Daugherty’s recent biography, Larry McMurtry: A Life offers a faithful, often revealing, window into this ineluctably lonely man’s life. But it’s hampered by the inevitable limitations of chronology. Lost in the iterations of boyhood, early and mid-career success, romantic adventures and disappointments and an inevitable late-life decline is the lyricism that distinguishes his work at his best. As McMurtry mused for an oral history of Lonesome Dove published in the Texas Standard: “For an essay, you have to think from sentence to sentence and make one follow another. Fiction is less conscious. It’s a trance-like experience for me. I see the characters, listen to what they say, and write it down.’’

How he was able to do that with apparent ease, for much of his literary life, remains a mystery—one suspects as much for the author himself as his readers.

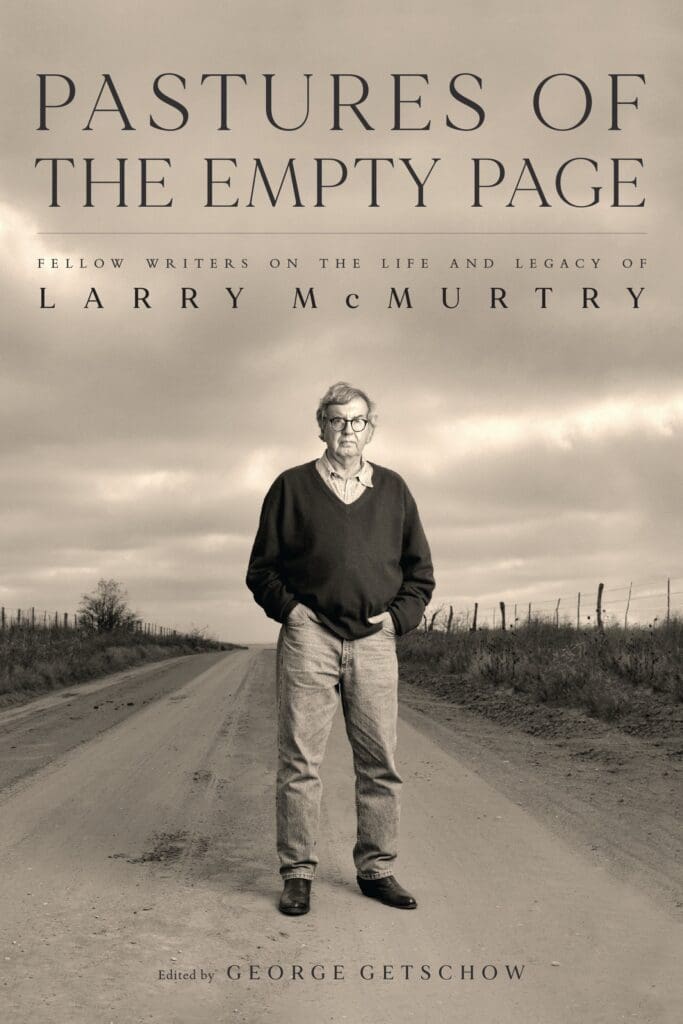

A new collection, Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry (University of Texas Press; 272 pages), gestures toward that mystery, and enchantment. Edited by George Getschow, director of the Archer City Writers Workshop, this festschrift of tributes from those who knew him, or wanted to, may border on hagiography at times, trying to clutch the cloak of this laconically Garbo-esque figure, who hated being pushed into a corner to assess, or even describe his work. But it still comes closer to catching the man, even if only in relation to his impact on others.

“McMurtry was not always the friendliest man,’’ Skip Hollandsworth allows. “In 2016, when I visited him in Tucson and Archer City for a Texas Monthly story I was writing, he always seemed bored and wanted to change the subject whenever I asked him about his accomplishments. He grunted at my queries about his ‘writing process.’ When I called him to ask follow-up questions, he got so tired of talking with me that he hung up the phone without saying goodbye.”

Recovering journalist and screen scribe William Broyles describes taking McMurtry’s Rice University creative writing class in 1965: “On the first day Larry announced that we’d be writing our own short stories and reading from them in class. He then walked to the board and asked us to not write about several topics. As I recall, he wrote on the board: ‘How I lost my virginity, ‘My first LSD trip,’ etc.’’

Devotee Geoff Dyer, one of the few non-Westerners in the new collection, likens his absorption on first discovering Lonesome Dove to “the spell famously evoked by Wallace Stevens, “the reader became the book. … There was no book and no reader. There was just this world, this huge landscape and its magnificently peopled emptiness.’’

Let’s take the distinction between “popular’’ writing, created for the proverbially mindless masses, and “literary fiction’’ off the table.

McMurtry’s work has often seemed to be a guilty pleasure, at least in contrast to the reverence accorded to contemporaries like Cormac McCarthy.

As the late, lamented, redneck arts tailgunner Dave Hickey once put it: “Professors ignore Larry because you can’t teach seamless talent. He does what Henry James did; all the ideas and commentary are subsumed in the narrative, and trying to teach that would be like using Stevie Wonder to teach songwriting.

“McCarthy, on the other hand, is house-proud. It’s this collage of antique and modern prose, chock-full of tropes and maneuvers—pure professor bait. They’re also drawn to his unrelenting pessimism. He has this little tic characteristic of small children—whenever we’re having a good time, somebody is about to get shot.’’

With becoming modesty, McMurtry never claimed to be in the same league as the nineteenth century greats he admired, let alone Cervantes, the patron saint of Lonesome Dove. But he was equally direct about his peers. As he told Texas newspaperman/screenwriter Bill Marvel: “It’s okay to be minor. I think when you boil down the Mailer-Roth-Bellow generation, there’s not really much that I wouldn’t call minor.’’ (He exempted Flannery O’Connor from the general dismissal.)

After moving through most of his early and mid-period works, I finally got around to Lonesome Dove, and appreciated its inarguable merits. (Like the author, I’ve never watched the miniseries, though I’ll take it its merits on faith.)

But McMurtry never lost sight of the irony that this demythologizing project—conceived originally as a film script for Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda, and John Wayne (who turned down the script because it was too downbeat)—would ultimately revive (and commodify) the promise of the Golden West.

Often described as epic, it clocks in at a cool 843 pages. Notwithstanding the inescapable appeal of Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call’s epic cattle drive, I still prefer Moving On, an even longer (1,008-page) novel, published in 1970, with its vivid portrayals of tearful heroine Patsy Carpenter, escaping from a loveless marriage, screen writer Joe Percy, rodeo rowdy Sonny Shanks, and other stock characters whose progress we get to chart in his subsequent works. The challenges of modernity, and the pull of the past, were his great subjects.

I liked McMurtry’s original title, “The Country of the Horn’’ better, too. His editor, Michael Korda, overruled him. but now admits it was a mistake. A more aspirational approach might have helped the book’s reception—it received middling reviews, and sales—but probably not.

People do like their Westerns.

Paul Wilner is a longtime poet, critic, and journalist based on the Central Coast.