Many stories are, in a sense, mysteries, asking some version of the same question: what is this life, and how are we meant to live? There are, of course, no definitive answers to these questions—only a multitude of responses, from which we seek to make the meaning and beauty that connects and sustains us amid persistent uncertainty.

One such story is The Postcard (Europa Editions; 475 pages). Written by French author Anne Berest and translated by Tina Kover, the novel frames the true story of a family—nearly eradicated by the Holocaust—as a fictionalized memoir. Nestled inside a simple and concrete mystery (who sent the narrator’s family an unsettling postcard, and why?) are thornier questions about what it means to be Jewish; what it means to be a Jew in France; and about how the children, grandchildren, and now great-grandchildren of survivors are affected by the trauma of the Holocaust. While the framing mystery instigates a productive investigation, the questions posed by the subtextual story can seemingly only be acknowledged and left open-ended, haunting both the narrator and reader.

The book opens in January 2003 in Paris, when the narrator (also named Anne Berest) tells us her mother (Lélia) received a postcard with the names of Lélia’s mother’s deceased parents and siblings, all killed by the Nazis in concentration camps. Lélia’s mother, born Myriam Rabinovitch, was the sole survivor. There is no other text on the card, just the names: Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie, and Jacques. Myriam is no longer alive, and the unusual handwriting is unrecognizable to Lélia. Disturbed but unwilling to dwell on this inscrutable episode, she puts the card in a drawer and moves on. Ten years later, stirred by the emotions of expecting her first child, Anne asks Lélia (evidently for the first time) to tell her everything she knows of their family history. Several years later, Anne and Lélia are both rattled when Anne’s daughter, Clara, now six, asks her grandmother whether she is Jewish. When her suspicion that she and her mother and grandmother are all Jewish is confirmed, Clara tells her grandmother, “They don’t like Jews very much at school.” For Anne, this experience brings to the fore a host of issues about her family’s heritage that suddenly feel urgent—and incites her quest to decipher the meaning of the anonymous four-word postcard and gives rise to a nearly 500-page novel steeped in the author’s background.

There are intricacies of genre and storytelling, layers of personal and world history, and degrees of psychological archeology at work here. Berest makes maximal use of the opportunities afforded by autofiction (the blending of fiction and memoir, or fiction that is highly autobiographical), taking a novelistic approach to inhabit the interiority of her murdered ancestors. The book revives the lost world of the Rabinovitch family at several removes; Myriam, like many survivors, did not talk much about her past, so Lélia spent years privately researching what happened to her family. The Rabinovitches’s past is presented in the form of Lélia talking to her daughter, with frequent, detailed descriptions of their most intimate thoughts, feelings, and conversations.

The story begins with the marriage of Myriam’s parents, Ephraïm (a talented engineer) and Emma Rabinovitch, in Moscow. The series of ultimately fatal decisions Ephraïm makes are linked to his profound ambivalence about his Jewish identity: in 1919 he is 25 and “had great ambitions for his country—and for the Russian people, his people, whom he hoped to join in the Revolution. Being Jewish meant nothing to Ephraïm. He considered himself a socialist, first and foremost.” That same year, Ephraïm’s father urges the entire family to leave Russia and emigrate to Palestine. “It stinks of shit,” he tells them in Yiddish, referring to the prospect for Jews in Russia and Europe. He pleads with them to go to Palestine with him, or at least to the United States. But Ephraïm is unconvinced. And when he eventually moves with his wife and children to France, he brings with him this tragically misguided confidence in assimilation.

Through Lélia and Anne—by blending fiction and nonfiction—Berest breathes life into her scaffolding of documents, images, and historical context, making her characters as full as she can. She renders these lost lives with the weight of specificity. The scale and extremity of the Holocaust create a risk of abstraction, and incomprehension; such specificity works vigorously against both.

The book is most devastating when describing the horrors inflicted on the Rabinovitches in their final year, as the walls close in: the way the perimeters of their lives are reduced; the conditions and abuse Jacques and Noémie endure at the transit and internment camps in France, before being sent to Auschwitz; the agony Myriam witnesses and endures when looking for her family at a makeshift hospital for survivors in Paris after liberation. Memorably chilling, too, is the visit Anne and Lélia make to the small French town where the Rabinovitches last resided. Berest’s detailed research, combined with her acute empathy for her relatives as specific people whose personalities she makes vivid for the reader, give these pages an immediacy that is tense and unbearably sad.

Through layered timelines and narratives, the book also effectively renders the sense that, as Maurice Blanchot memorably put it, the Holocaust (or “the disaster”) collapses time. Here the voices of the murdered are brought into the present through the labor, imagination, and grief of the living. Anne and Lélia endeavor to find the story of what happened to their family, and in the process discover that there is no end to the ways in which they are connected, and no way to fully understand or articulate the depth and complexity of their fraught connection to their dead ancestors.

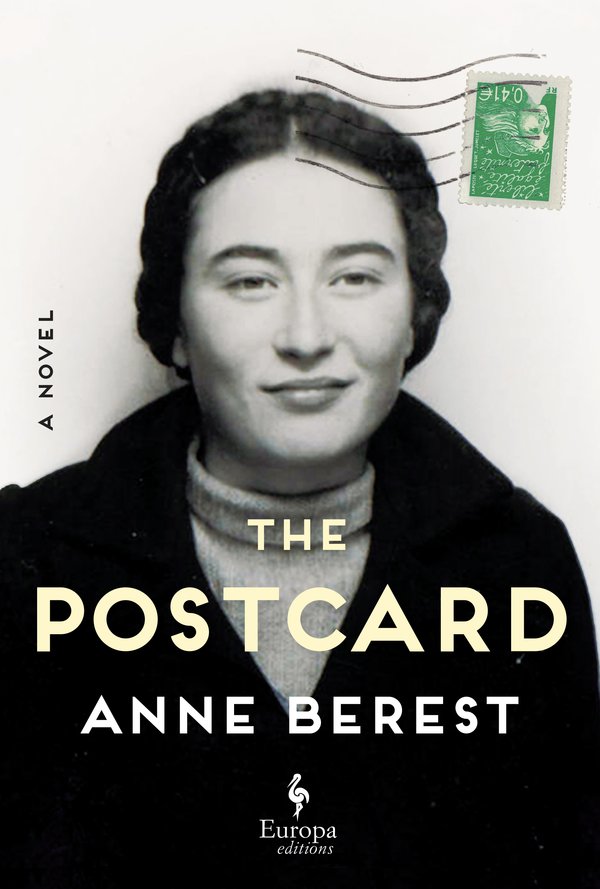

Rarely does a book make as clear an argument for the use of the autofiction technique as The Postcard. But, with the historical stakes raised so high, questions are raised that would not be significant in other contexts; namely, why not publish any of the referenced letters, government documents, or photographs? We’re given to understand that elaborate research has amassed a trove of documents upon which the historical backbone of the narrative—and many of its significant details—is based. Presumably these documents are real—indeed, I think it’s important that readers can trust that they are, particularly considering how Holocaust denial has flourished in recent years. Yet The Postcard is notably free of any reproductions of documents, maps, photographs, and letters. Only on the jacket copy is the striking cover image acknowledged to be Noémie Rabinovitch (in 1941, the year before her murder at Auschwitz). Noémie’s journal and unfinished novel are quoted from, but it’s not made explicit whether these sections involve any fictionalization on Berest’s part. Even the postcard in question appears only in a thumbnail image on the book’s flap.

There are other awkward angles to this hybrid narration, too. Occasionally, Berest breaks up the narrative (presumably to sustain the fictive framework of a conversation while all this family history is being shared) by having Anne ask Lélia a question. Some of these exchanges have a contrived quality. Anne’s queries sometimes feel leading, or jarringly rudimentary, raising questions about the intended audience. In one especially strange moment, Berest refers to Pesach as “the Jewish Easter.” It’s unclear for whom this explanatory aside is meant (does Lélia mean it for Anne? Does Berest mean it for the reader?), but it’s incorrect in any case. Some readers will, of course, know that Pesach celebrates the Jewish exodus from slavery in Egypt; others may now have a false understanding. Errors can creep into any book, but given the context—the violent erasure of Jewish culture from Europe—this is a startling one.

Perhaps it is not only a painful error, but a telling one. As the heroine of her own book, Berest has gone to great lengths to dispel the ghostly silence that was her family’s legacy after the Holocaust. But one aspect of her quest to reconnect with her family’s history remains a confounding blank at the center of the book, the question around which she restlessly paces but does not seem quite ready to answer: What does being Jewish mean to her?

Lélia and her husband raised Anne without Judaism; they embraced contemporary French ideals of secularism and equality. But in the absence of any celebration of Jewish heritage, the only remaining connection to Judaism was the Holocaust itself, and its reverberations through her family’s life. Anne describes how, as a teenager, she felt a sense of loss where her connection to Judaism ought to be. In one episode from her schooldays, “Four or five girls explain to the phys ed teacher that they won’t be participating ‘because it’s Yom Kippur.’ I envy them and feel excluded from a world that should be mine. … I feel like the only thing I truly belong to is my mother’s pain. That’s my community. A community made up of two living people and several million dead ones.” Without question, Berest is not alone in her feeling of inherited loss, in this sense of carrying death within her. The idea that survivors and their immediate descendants suffer physiological effects of trauma at a molecular level is not fully understood, but has been around for quite some time and is an expanding field of research for psychologists.

So how to understand the aftermath of the Holocaust? In Eva Hoffman’s After Such Knowledge, a sensitive and thoughtful book on the subject, she writes, “But what happens when we focus on ‘memory’ itself rather than its object, on the rituals of remembrance rather than their content? For something like that seems to have happened on the way from the era of ‘latency’ to that of ‘memory,’ from forgetfulness to fascination.”

It’s a troubling and important question, not only because, as Hoffman writes, “as the age of living memory comes to an end, and as the human conduit to the Shoah becomes attenuated, we are all entering the age of virtual memory,” but also, and most essentially, because the Holocaust is not the foundation of Jewish culture, and, while central to the experiences of survivors and their descendants, it cannot function as the foundation of Jewish identity.

The global population of Jews has yet to reach pre-Holocaust numbers—and, of course, in Europe the devastation remains most acute: on the continent where over 9 million Jews lived in 1933, there are now just 1.3 million. That’s grim enough. But what of Jewish culture in Europe, beyond the numbers? There must be a place for Jewish culture if Jews are to thrive in Europe—and assimilation will never be the answer.

Assimilation and its complexities are not uniquely French issues, of course, but given that France is home to the largest population of Jews in Europe, it is of special significance. And it is perhaps not surprising if both its history and elements of its present culture—the prohibition of religion in public spaces and broader cultural pressure toward secularism, shame over its history of antisemitism, and reluctance to acknowledge the realities of the occupation—make for a notably challenging environment for Jewish identity. Even Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous 1946 treatise against antisemitism, Anti-Semite and Jew, doesn’t go so far as to envision room for Jewish identity in France, focusing its critique instead on the vileness of antisemitism and on contempt for the prejudiced. His suggestion that the antisemite will define the Jew as they see fit is insightful: prejudice reveals something about the bigot, and nothing about those it dehumanizes. This has, unfortunately been borne out historically—but it is also woefully incomplete. Sartre’s perception was limited by his lack of interest in understanding Jews as defined by themselves.

“I was turned into a Jew by others,” Primo Levi said in 1976. So many layers of pain and anger can be inferred in that terse statement. But there is profound meaning—and joy—in defining Jewish identity for oneself. After attending her first Pesach seder—as an adult, amid her investigation into the postcard—Anne writes: “You can’t imagine how beautiful I found that Pesach celebration. How could I have missed something so deeply that I’d never done before?” Anne’s alienation from her Jewish heritage can only partially be addressed and redressed by the exacting and tireless work she does to investigate and narrate what happened to her family. How does she wish to be Jewish in the present, and the future? Will she raise her own daughter with any of the traditions she felt excluded from, growing up in a strictly secular home? We can’t know, but Anne’s strong reaction to the beauty of that seder suggests she may pursue a connection to Judaism. It speaks to a journey, not yet concluded, from the early pages of the book, where Pesach was a foreign idea, rather than a cherished experience.

I wrote this review in September, and in doing so spent a good deal of time thinking and reading about the Holocaust and its aftermath—but also about Jewish resilience and Jewish pride. On the morning of October 7, the terrorist organization Hamas attacked civilians in southern Israel. More than 1,000 Israelis were murdered, making this the largest massacre of Jews since the Holocaust. My heart is with the Jewish community, and I grieve for the innocent civilians in Israel and in Gaza who will suffer in the weeks to come. Am echad b’lev echad. Am Yisrael Chai.