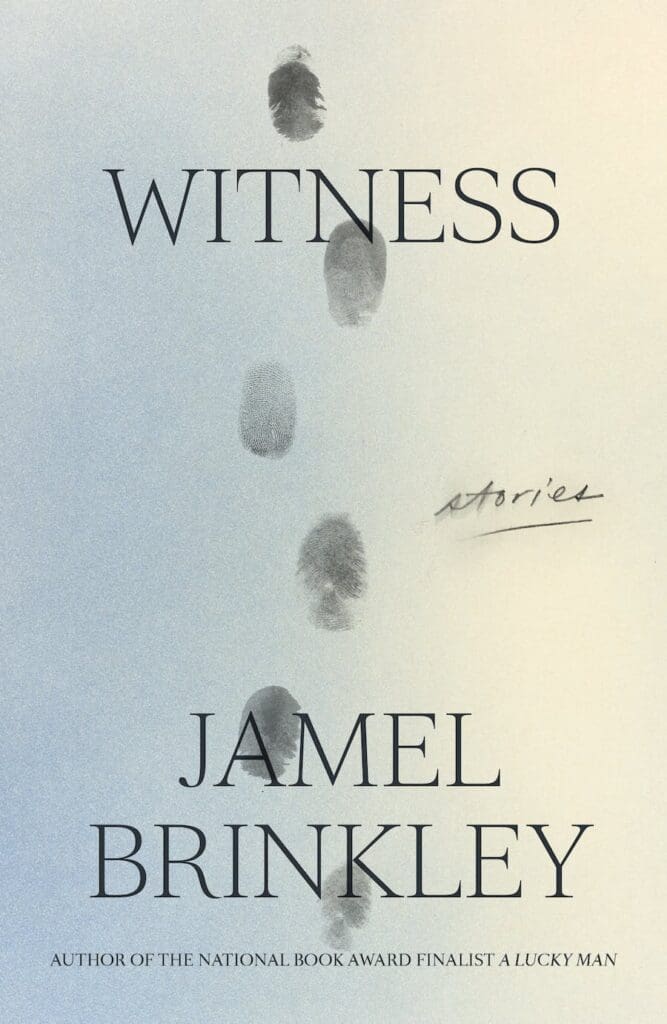

Jamel Brinkley’s second story collection, Witness (Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 240 pages), records glimpses of lives across New York, disparate but proximate—as though looking at people in lit windows across the cityscape. Lingering in the worlds and heads of his protagonists, Brinkley’s stories elongate these moments into chasms of psyche and memory. They remind us that whatever we see in the window, observation alone is superficial. To witness is a full-body experience, affecting the mind as much as the eye.

New York is a familiar setting for Brinkley, whose debut, A Lucky Man (2018), also features stories set in the city. In Witness, place is not merely a backdrop but a part of the self. When you always see someone in a certain context, as Gloria hypothesizes in “Sahar,” you may not recognize them elsewhere. “Your eye can take in all of the person’s features but they don’t mean anything, they don’t organize themselves into something substantial enough to seize upon. The person, simply put, is out of place.”

But a sense of belonging to place is compromised in changing New York neighborhoods where the old churches and diners are shut down, family homes are unwittingly signed away in deed thefts, and language is changing. Witness casts gentrification through a personal lens. In the collection’s first story, “Blessed Deliverance,” a group of five high school friends in Brooklyn seem to fall apart just as the streets they grew up on become unrecognizable. The act of naming—significant throughout the book—signals a shift: “[We] invoked Toby for Kunta Kinte, SoHa for lower Harlem, DoBro for downtown Brooklyn, all the examples we could think of that illustrated the ways they claimed the right to name and rename whoever and whatever they pleased.” Although the story is narrated through a collective “we,” its perspective is tied to the one unnamed friend who is left alone as the group fractures. The loss of a past Brooklyn serves as a double isolation. “The thing was to remember,” the narrator declares, “to use our minds and their keen branching tails” to recall the spaces replaced by new businesses. It is as though his attempt to evoke the streets is to bring back the good times of belonging, before “we” became an “I.”

As it confronts the specters of lost neighborhoods, traditions, and people, Witness becomes a book of haunting. The problem of vanished place is also the problem of time. Gloria reminisces about the days of camaraderie with her colleagues at the Q Hotel, of room service and bellhops and hailed taxicabs, back when the neighborhood had another name. In “Arrows,” a literal ghost appears in the form of Hasan’s late mother, painting her nails and brushing on makeup in her old bedroom. Those who fixate on the past, Hasan believes, tend to get impaled by “the arrow of time” and become ghosts. Hasan’s mother is near-corporeal, making it difficult “for living witnesses to keep the necessary boundary, to distinguish between traces of things and the things themselves.” History persists into the present. In Brinkley’s stories, the younger generations bear the inherited hands, eyes, and faces of their ancestors, at times confusing older characters. “When I first saw you,” Ramona says in “The Let-Out,” “I couldn’t believe it. It felt like 1989 all over again.”

One of Witness’s three epigraphs is from “The Reason for Stories,” a 1988 Harper’s essay on fiction and morality by Robert Stone. It introduces a challenge to pure witness, the fickleness of human senses: “The world is full of illusion.” Brinkley is just as interested in what can’t be easily seen, the invisible realm where it’s difficult to tell what the truth is. Time passes vaguely; what one character sees in the mirror may diverge from another. “I don’t think it’s a real memory,” the narrator of “The Let-Out” tells Ramona. “I’m pretty sure I made it up.” In “That Particular Sunday,” two cousins speak of their childhood and return different memories. The narrator claims he is referring to “the actual past, the genuine past, the Sundays that had the patina of the golden age, time’s verifiable signature.” But his cousin Mary declares, “I’m almost certain that that’s not how it happened.” The mind manipulates experience, willingly or unwillingly.

In the final story, “Witness,” a Black woman’s pain is continually ignored by white doctors, but also her younger brother. Brinkley complicates what we think we know and reveals that what we see is never only one thing. Witness reveals racism in the medical system through a story of siblings; gentrification through an eight-year-old’s eyes; the strain of each day on a young woman four years after her brother is killed by a police officer. In every story, Brinkley pulls off an illusion: to show what we cannot encounter simply by looking.