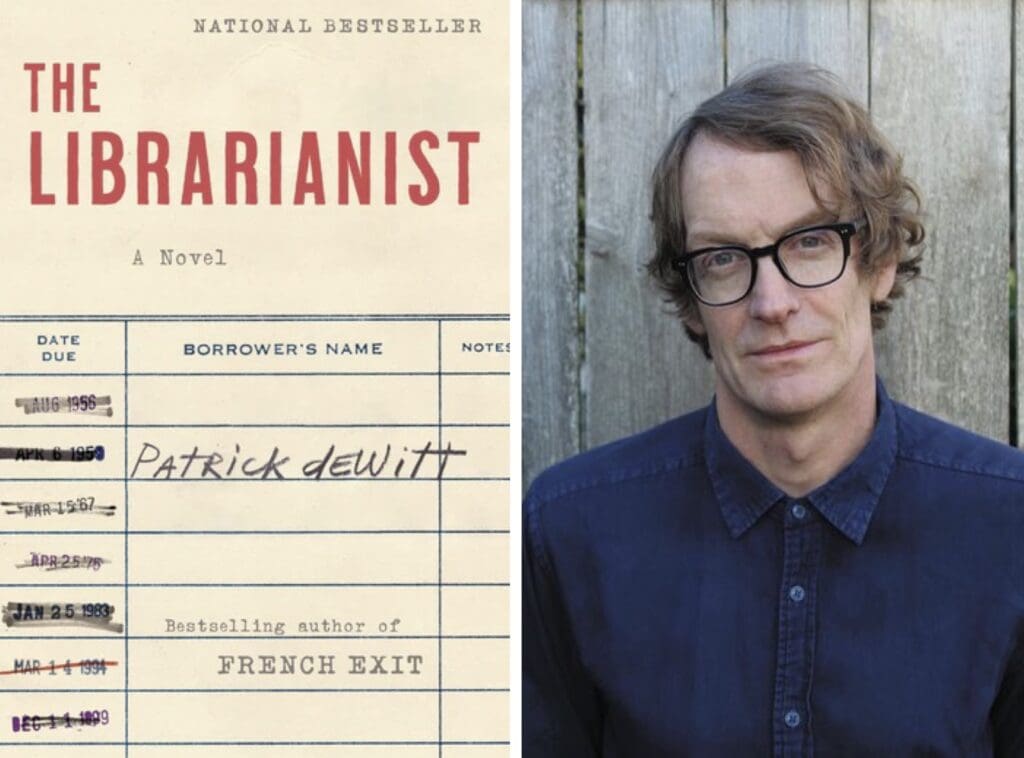

The name “Comet” evokes the fiery and dramatic path of a celestial body, the kind that might portend the end of the world, or at least make for good cinema. But a comet is also a solitary thing, moving silently through the solar system. In Patrick deWitt’s new novel, The Librarianist (Ecco Press; 352 pages), Bob Comet is the curiously quiet carrier of this name.

Bob is a protagonist out of step with time and life. On deciding to become a librarian, his mentor tells him that “librarianism doesn’t hold up in our society’s real time … the language-based life of the mind was a needed thing in the syrup-slow era of our elders, but who has time for it now?” The Librarianist demands an unhurried pace. It is a study of the small life, its beats made up of ordinary comforts and hushed devastations. While deWitt keeps the voice from ever becoming too sentimental, there is a dreamy texture of melancholy that rarely lets up. To read The Librarianist is to yearn, achingly—but for what, exactly, never quite comes into focus.

In 2005, when the novel begins, Bob has retired and maintains an unassuming daily routine. He seeks doses of the unexpected in his long walks in Portland, Oregon. DeWitt shows how easily the surface of the orderly world can be punctured by hysteria. Outside a veterinarian’s clinic, a man rips out flowers from their beds as dogs look on. In a 7-Eleven, Bob is warned that a motionless woman in a pink sweatsuit might “freak out” in any number of ways. After leading this woman back to the Gambell-Reed Senior Center, Bob begins to volunteer there. This first section of the novel is filled with the troubles of the residents. It’s a little sluggish, but deWitt’s specialty—sharp dialogue between eccentric characters, as in his novels The Sisters Brothers and Undermajordomo Minor—is dished out plentifully enough to entice the reader to Part Two, when time turns back to the 1950s and the pace picks up to a pleasant amble.

Although Bob is often passive, the novel centers on his few resolves: volunteering at the senior center, becoming a librarian, falling in love with his wife, Connie, and running away as a child. DeWitt has described Bob as an “unheroic individual,” yet fate lurks about this book with the foreboding of Greek tragedy. At the start of the story, Bob’s great heartbreak is revealed; just after he marries Connie, she runs away with his best friend, Ethan, an event he had a prophetic sense would happen: “Here was the beginning of his realization that there was something dangerous moving in his direction, and that he wouldn’t be allowed to escape it, no matter what clever maneuver he might invent or employ.” An ominous hiking scene imitates Orpheus’s walk with Eurydice out of the underworld. Bob is in front, Connie in the middle, and Ethan at the back: “He walked on, carrying his worries, and he told himself he wouldn’t look back, not even once, but then he did, and he saw Connie was herself looking back at Ethan.”

The jump to Part Three moves the story to 1945, when eleven-year-old Bob runs away to the Hotel Elba. The section is delightfully kooky, thanks mostly to the dynamism of traveling thespians, June and Ida, who take Bob under their wing. Yet the childhood adventure story seems incongruous, set apart from the Bob-Connie-Ethan affair that otherwise anchors the novel’s time shifts and wistful tone.

Although the condition of the introvert is a fascinating one and worth a novel’s exploration, Bob himself is at times vacant rather than reserved. At his center is a strange absence: “Bob sometimes had the sense there was a well inside him, a long, bricked column of cold air with still water at the bottom.” Growing up, Bob was mostly invisible, without close friends, and had neither a charismatic nor horrible personality, but was “to the side, out of the race completely.” He imagines that Connie wonders, “Why do you read rather than live?”

Bob’s character is deWitt’s principal curiosity but too often becomes the novel’s trap. DeWitt turns away from where the tension might be raised, the desire followed, or the betrayal confronted. Bob’s memories “hiding in a corner of his mint-colored house” are never truly reckoned with. The emotional consequences of Bob’s decades of passivity are muted, and no urgent dilemma ever unfolds from the novel’s revelations. The Librarianist shines when its minor characters force their way into Bob’s life and divert his trajectory, reviving the story in unexpected moments like those Bob craves on his long walks.