A writer’s last work, the mere fact of it, ineluctably changes its meaning. Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s Kappa (96 pages; New Directions; translated by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda and Allison Markin Powell), is one such finale, the coda of a brief yet prolific career, a novella first published in 1927, months before this acclaimed author would kill himself. What does this book divulge about his psyche? Can this most condemned act be made legible? And it’s even more grotesque—but unavoidable—that one wonders if this work, written by the namesake of Japan’s foremost literary prize, is significant only because it’s his last.

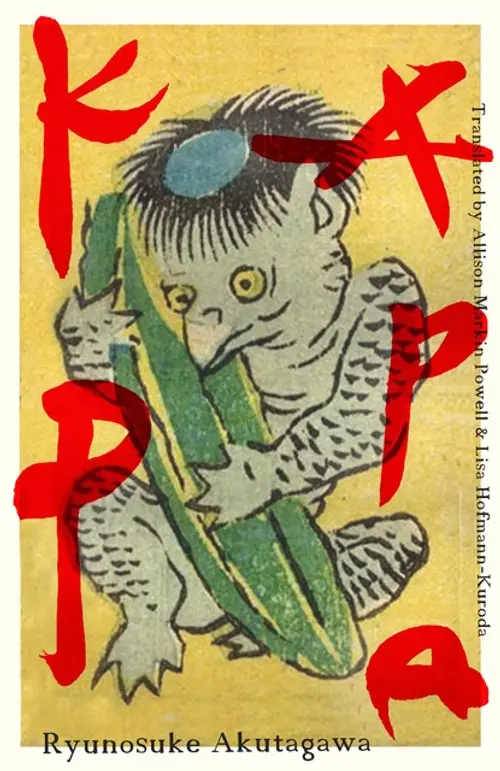

Akutagawa’s narrator, No. 23, is a schizophrenic at a psychiatric hospital who’ll tell a peculiar tale to anyone who listens; it begins several years before his internment during a fog-shrouded hike. Disoriented, No. 23 sits to rest when a kappa—a creature from Japanese folklore—suddenly appears. He chases it until, the yōkai almost within reach, he trips and stumbles down a hole, landing in Kappa-Land. Froggish, beaked, and roughly child-sized, they’re known as malevolent tricksters, luring children to their deaths in waterways. But No. 23 is surprised to find Kappa society remarkably human, with industrial factories and motorized vehicles, a functioning judicial system and media, and both artists and scientists alike. It’s their manners and customs that he finds alien, as if everything Kappa is opposite. Young, single kappas are recruited to the “Genetic Volunteer Corps,” paired with unhealthy partners to eliminate “bad genes.” Strikes are prohibited and, instead, the labor problem is resolved by killing and eating worker kappas.

Kappa is “Gulliver-esque” in that it shares the motif of a lost visitor in a far-off land and, because Swift and Akutagawa use a congruence between a fictional world and reality to advance social criticism. The dissonance between Lilliput or Kappa-Land with contemporary society is only superficial—better yet, a subterfuge for polemic, blatant as it is. The novella’s venom is cast at Japan during its Jazz Age, the Taisho Period (1912-1927). The country had been isolationist until 1853, when forcibly opened by Admiral Perry’s Black Ships. Confronted by Western technological superiority, the government implemented a program of modernization and rapidly transformed Japan from a feudal society into a fully-fledged capitalist nation. The Taisho Period began with the ascension of its namesake, Emperor Taisho, in 1912; during his reign (though only a figurehead), the country experienced great prosperity and liberalized politically and culturally. It was one of those rare moments in history when artists could create without consequence—one that Akutagawa and his peers seized with vigor.

The Western influence on Akutagawa and other Taisho literati is pronounced. Thinkers and writers across the Western canon were translated and eagerly consumed by the reading public. New formats such as the novel and short story—the latter being Akutagawa’s preferred medium—were melded with traditional Japanese forms. Socialist ideas spread alongside industrialization, producing the genre of proletarian literature, while the loosening of cultural mores allowed experimentation with the erotic, grotesque and absurd. Kappa combines these elements, like furikake, bits and parts of both Eastern and Western origin to form a novella that belies categorization, an ideal medium to sledge the facade of order and progress erected by the powerful. His gaze was perspicacious: Akutagawa wrote and published Kappa at the end of the Taisho Period, when Japan started to oscillate rightwards amid economic uncertainty and growing imperialist aspirations. Authorities had begun to suppress the political left and its artists under the auspices of national unity. Art had to defend against the counterrevolution, Akutagawa believed, to protect freedom and plurality in the public sphere; in a noteworthy scene, the Kappa police barge into the musician Craback’s concert yelling “PERFORMANCE VERBOTEN!” The audience shouts back “POLICE TYRANNY!” while Craback, undeterred, plays on.

Yet Kappa is much more than allegory, considering how much Akutagawa reveals, often obliquely, about his inner world and the psychic torment that plagued him. The story itself is soaked so thoroughly with topic of mental illness, whether it is the schizophrenia of its narrator, the anxiety of the student Rapp, or the severe depression of Tok the Poet. Commentary is not needed—it’s an instance where a statement of existence is enough, where the ubiquity of mental illness in Kappa reflects real life, a profundity that lies in the reality that despite its prevalence, inner anguish is often left unspoken.

Akutagawa’s condition was congenital and circumstantial. Born to a prosperous Tokyo family in 1892, he had a stable but unnerving childhood. He was raised from an early age by his aunt and uncle because of his mother’s severe mental illness, and his adolescence was stained by the constant fear that he’d inherited her condition. It was a specter that haunted their relationship and that only intensified, a destructive complex likely emanating from the subconscious realization that he did inherit her affliction. His adoptive mother, his aunt, was a domineering figure, demanding and controlling at the expense of his self-esteem. His mother’s resignation alongside his aunt’s overbearingness would seed an eventual disdain for women. Akutagawa saw the female sex as an irritant, if not a menace to men, a fount of incessant belittlement and emotional turmoil. Even in Kappa, females aggressively pursue males, haranguing them verbally and physically, a predicament for male kappas who need companionship but suffer dearly for it.

It’s through Tok the poet that Akutagawa makes his final confession. Tok is trapped in contradiction, one shared by many great artists—at once, he’s supremely confident of his abilities but dreadfully uncertain of his stature. He isn’t sure if he’ll be read and remembered, but also confident that “everyone will buy my collected works in three hundred years—that is, once the copyright has expired.” Is it possible not to project this sentiment onto Akutagawa? The last years of his life were miserable, steeped in physical and emotional agony, and he attempted suicide multiple times. An artist’s vocation is their purpose, and if accosted by finitude, as he was, their art also becomes a totem of their existence—a legacy. Through Tok, Akutagawa expresses one of his deepest wishes: to be remembered long past his suicide, an afterlife not in the heavens but in the permanence of his writings.

Kappa is one of those strange stories where, taken in pieces, none of the techniques, characters, nor commentaries are exceptional, but nonetheless possesses that inexhaustible quality that good books have. Its distinction is enigmatic, lying between the confluence of social and personal, at the intersection of Japanese tradition and Western modernity, bound in the bizarre Kappa-Land. Undeniably, the book’s reputation is tied to its late author’s suicide, and one even wonders if Akutagawa intended this, as if its social commentary and personal confession anticipate his death. But it’s a testament to his ability that those unaware of Akutagawa’s life, of his misery and woe, will appreciate his last effort.