Poetry can encompass many shapes and qualities, including the singular capacity to open new pathways of understanding ourselves. A poet who achieves this feat is unafraid to take risks and question the quotidian. Eileen Myles has consistently been one of those poets. Myles’ newest poetry collection, a “Working Life” (Grove Atlantic Press, 267 pages), is perhaps their deepest and most personal exploration of what it means to be human. Myles says that “maybe time is the real subject of language,” and uses temporality to explore personal and public moments within a broader sociopolitical landscape.

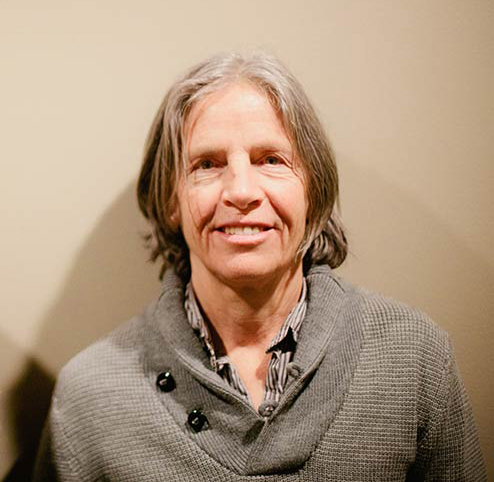

Born in Boston and now living in New York and Marfa, Texas, Myles is the author of more than twenty collections of creative works, as well as the recipient of multiple fellowships and awards, including the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Creative Capital grant, and three Lambda awards. They are widely established as one of the most prolific writers of their generation. This interview was conducted via email and has been edited for clarity and length.

ZYZZYVA: While your work has always been conversational and experimental, this collection strongly exudes these qualities through its resistance to a sole voice or form. What was the process of writing this book, and what surprised you about it?

EILEEN MYLES: I definitely have not written this book before, but I’m writing it again. It feels like a restatement of what I ever meant by poetry. I’ve always wanted all the time in the world like I had when I first came to New York in the 1970s, and the pandemic gave it to me. Many of my projects fell to the wayside and a lot of poems and the editing of [the anthology] Pathetic Literature came to the front. Every moment seemed to have a poem and there were irreconcilable things like my absence from the person I was dating, which was the source of “Put My House.” “Casper” was a fallout from a film that’s on YouTube called The Trip. A puppet speaks and I thought his monologue was a poem. It was very particular to the place I was writing from, which was Marfa and then New York and the fight to save East River Park. I thought of policy in the city and poems being a way to occupy a day, this sudden free space. I felt like it was a model for living a working life.

Z: In “Howl,” I was struck by the line “people are always talking full of love & pain.” Many of these poems make space for pleasure and suffering to coexist, which has been especially relevant throughout the pandemic. How do you use poetry to navigate love and pain, or tension between the two?

EM: Well, I have this tiny mouthpiece which is a poem. I could sit in a Zoom and write a poem about what I was hearing. I was aware of the suffering of the world in a certain way, more apart and then deeply centered. I really felt like I heard myself.

Z: In your most recent craft talk at NYU, you said, “I think the poet must pretend to be a regular person.” This book feels like an extension of daily living yet transcends reality through a mystical and observant lens. What is the balance between being a writer and “a regular person?”

EM: That has a lot to do with class, a shifting thing. Do I have privilege? Who am I speaking for? Am I allowed to speak? What class am I now? Of course, I am a regular person, but I’m really privileged, too. I don’t mean financially. I probably make less as a poet than a New York City teacher and definitely less than most academics. But my reach, though unpredictable, is also kind of huge. I don’t know what size I am but I’m not regular. Though regular sometimes.

Z: Time feels dynamic in this collection, pulsating at different speeds throughout each poem. Many of your poem titles are specific dates, but address temporality on both micro and macro levels. In “Time Today,” you write, “I’m unwrapping time today no I’m re wrapping it.” How do you approach something intangible like time within a poem?

EM: I’m held by it. It’s the real subject. I used to think a lot about this thing called bhava, which is the quality of the room, like the feeling when people are gathered in it. I think poetry negotiates that thing within you, like the soup of the day. I was drunk on time during the pandemic, so I had a more hands-on approach to it. Being alone a lot made time more of a subject than it ordinarily is, so it felt right to analyze and talk about it as the very language itself. Maybe time is the real subject of language or its materiality.

Z: I know you are passionate about many things, including dogs, trees, politics, and humanity. You regularly use social media to advocate for what you care about and address these subjects in your writing. What are the intersections between writing and activism?

EM: It was a new idea in the ’80s and ’90s that I could address the political in my poems. But since my concerns have become more specific, it just happens that my poems are vehicles for activism. I think about the park or dogs and the death cult of real estate in New York City much more than I ever did, so it pours into my poems more regularly like they’re taking the train with me.

Z: Form is something you are a master at, knowing how to blend shape and language together to tell a story. At what point in your writing process does a poem’s physicality come to the forefront?

EM: I’m not sure I understand what a poem’s physicality is. It is the poem. It’s how the poem comes. It’s how I want to be read, what I’ve read and what I’m writing on. And with.

Z: Many of these poems refer back to the pandemic and the initial stages of quarantine in 2020. What was your experience making art during such an uncertain period?

EM: Payday. Incredible. I did get sick in January of 2021 and was in bed for ten days and I watched all six seasons of True Blood, thus the vampires in the book which gave me such a way to talk about real estate.

Z: I recently reread some of your older works, including Evolution and Inferno, and was interested in thinking about these in tandem with a “Working Life.” How do you characterize this book in comparison to your other works?

EM: I was thinking of technology a lot in Evolution, taking pictures and inhabiting the city in a new way. It’s so weird that I began to more deeply know the city at that time and the park through my new dog, Honey. It was also an opportunity to put my pictures on Instagram, so those poems were a companion to that and some new striding emptiness.

Inferno was personal and also schematic. I wanted to show what a poet’s journey is and was. It’s such a great cultural unknown and my experience was so specific and rich. It was really a love poem to poetry and that life. It prepared me to write Afterglow because I was aware of how fictional fact is. In Afterglow, fact was filled with fiction. I loved thinking about how we make our dogs up, as well as live with them so specifically. I loved calling it a memoir since I was inventing more than any other book.