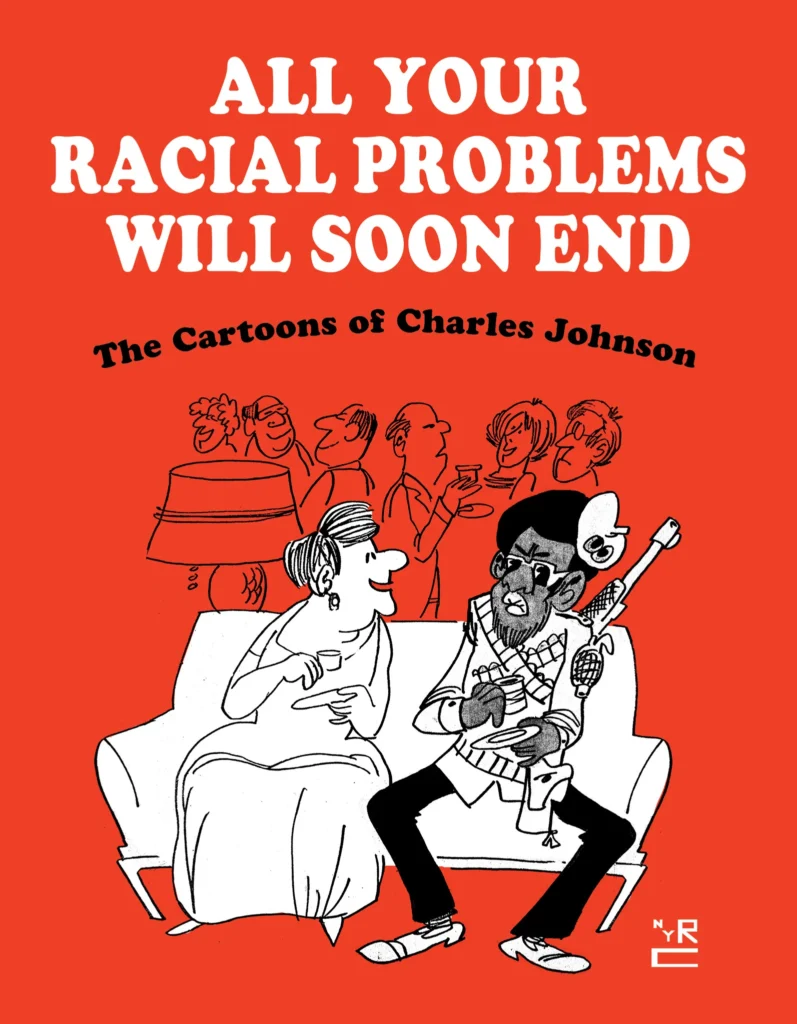

Charles Johnson’s collection of comics, All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End: The Cartoons of Charles Johnson (280 pages; New York Review Comics), is an especially provocative yet conscious-raising read in the wake of 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests. Spanning his entire career as a cartoonist—starting decades before his novel Middle Passage won the 1991 National Book Award—the collection focuses mainly on his most prolific era during the 1960s and 1970s, when his work explored black radicalism and the racism that birthed it. The comic strip may seem unfit for such weighty matters, but in the hands of Johnson—novelist, philosopher, and educator—it is weaponized humor, dismantler of the supposedly absolute.

Limited to a certain number of panels, the comic is necessarily brief, forcing the artist to convey a lot with little. This simplicity allows the comic to be widely understood and appreciated, a sort of democratic medium. Johnson himself draws a specific kind of strip called the “gag comic,” like Gary Larson’s The Far Side. Just one panel and one caption, the gag comic is particularly curt, and part of Johnson’s talent is that his comics represent and satirize race without reducing its complexities into cliches.

At the height of his career, Johnson’s work was never published in any major newspapers or publications. His comics dealt with topics too controversial for the mainstream, such as black economic exploitation, social inequality, inner-city housing, police violence, and American imperialism at large. But the true radicalism of these comics belongs in its portrayals of inter-personal experience. The unsettling feeling of cops at the door. The two-facedness of politicians making grand promises. The isolation of constantly being othered at the workplace. Conversely—the empowerment of radical education. The community found in political action. The pride of participating in the struggle. And hanging over it all, the equivocal realization that all your racial problems will not end but, perhaps, that some things can change.

Such a perspective is without equivalent in today’s comics. It is a gag comic like The Far Side, but whereas one is radically apolitical, the other is just as political. Doonesbury shares its acidic humor, but Garry Trudeau’s strip is only critical of a half, not the whole, of institutionalized politics. Robb Armstrong’s Jumpstart is unabashedly black, but the strip never leaves the confines of the middle-class experience. Darrin Bell’s Candorville or Aaron McGruder’s Boondocks may be closest in temper—both black and political—but neither are as radical or as devilishly frisky.

Perhaps the best description for Charles Johnson’s comics is black humor, in a twofold sense. Black first of all because the author and his characters are Black: Black Panthers, Black police, Black politicians, Black men and women, rich and poor. But Black also in that his subject matter is controversial, uncomfortable, to polite society. Unflinchingly, Johnson ventures into the projects and precinct alike, japing at what is painful yet true. Nothing escapes his interrogating gaze—anything can be lampooned, and, by extension, anything can be contested. Both humor and politics cannot take anything for granted.