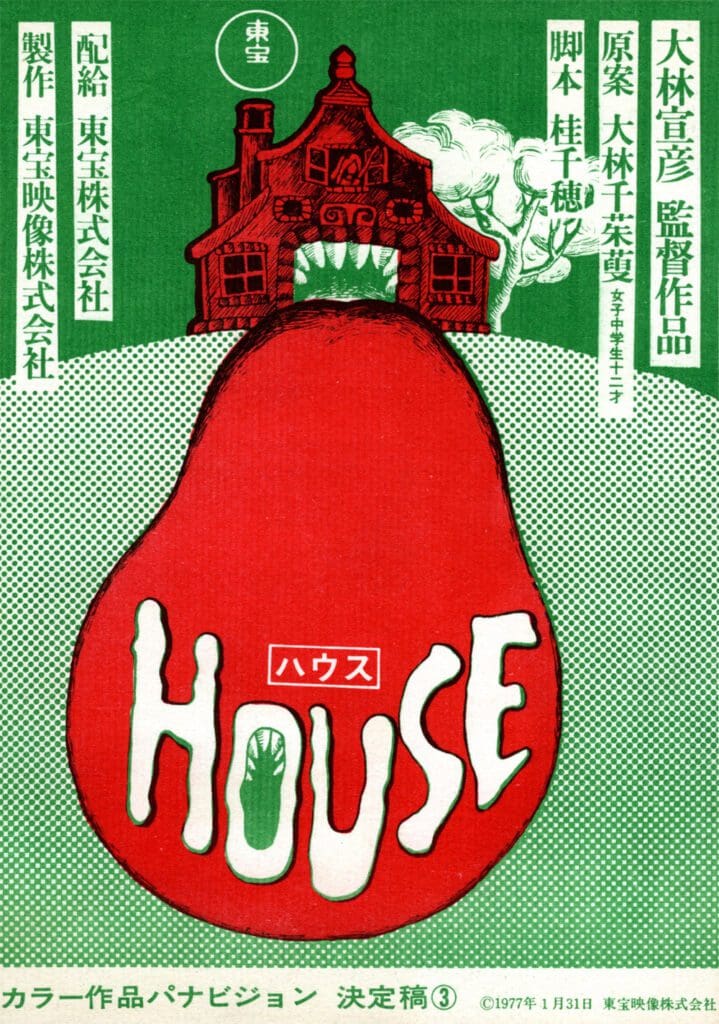

Danielle Shi, Intern: Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1977 film Hausu at first may seem like a comedy, as we witness scene after scene of innocent Japanese schoolgirls cavorting with nigh-homoerotic glee in the rolling countryside—until the haunted house they are staying in begins to kill them off, one by one. Think grand pianos chewing up fingers, tidal waves of blood to rival The Shining, and one particularly diabolical housecat that will leave you eying your own feline companion with (most likely) undeserved suspicion. Embodied in hallucinogenic animated sequences, cheesy and over-the-top special FX, and catchy musical numbers that repeat with a maddening frequency, Obayashi’s directorial achievement is guaranteed to startle you with its full embrace of the wacky avant-garde—with the added bonus of drawing out a belly laugh or two from its freeing, improvisational feel.

Aptly named ‘Gorgeous,’ our somewhat-useless heroine invites six of her close friends on a trip to a distant aunt’s countryside home, seeking to escape her overbearing father and his new Italian wife. Melody, Prof, Kung Fu, Fantasy, Mac, and Sweet: we could not get a merrier, more fun-loving cast, each bearing endearing traits of their namesake (Mac, for instance, is a big eater, and could probably be found making mac n’ cheese in the middle of the night or eating a Big Mac. She also gets teased relentlessly about this, the relational dynamics and cultural beauty standards of which are probably better addressed in a longer paper on the topic). It is unclear whether we are in the head of Obayashi or that of his co-writer—his young daughter—as we are presented with schoolgirls frolicking about and getting excited about summer vacation and sexy teachers. Girl power and female fantasy, in the spirit of Japanese shoujo manga (manga targeted towards young women), seem to have free reign.

Once at the house, the girls want to keep a juicy watermelon cool by putting it down the backyard well, a simple enough task, one would think. The plot thickens, however, when they become split up following Mac’s solo trip to the well outside—never, ever go anywhere alone in a horror movie, we want to admonish her with a groan as she succumbs to her genre-determined fate. When a vengeful spirit with a tragic backstory descends upon the girls’ heads, angry at their jouissance and untarnished youth, they band together, utilizing their various strengths and defenses to try and rescue each other, with oft-hilarious results: Kung Fu, for instance, perform high kicks in her athletica short-shorts as she comes in to save the day, and Prof uses her deductive reasoning skills to problem-solve like a true member of the intelligentsia…at least until she loses her glasses. Meanwhile, poor Fantasy gets repeatedly gaslit as the others dismiss her cries and claims as silly, the product of an overactive imagination—until someone else gets eaten by the piano(!).

I tend to watch few horror movies, fearing the hold on my dreams that their bloodcurdling images may have. Yet Hausu almost feels like a performance of horror rather than horror itself; the iconic gruesome scenarios, splatter gore, and supernatural elements feel exaggerated to the point of absurdity, rendering their fear factor null or minimal at best. Instead, what we come away with is an appreciation for the shock value that horror enables, as well as a healthy fear of what feels evil and repugnant to the senses.

We return, I think, to ourselves a little more sure of what feels right.

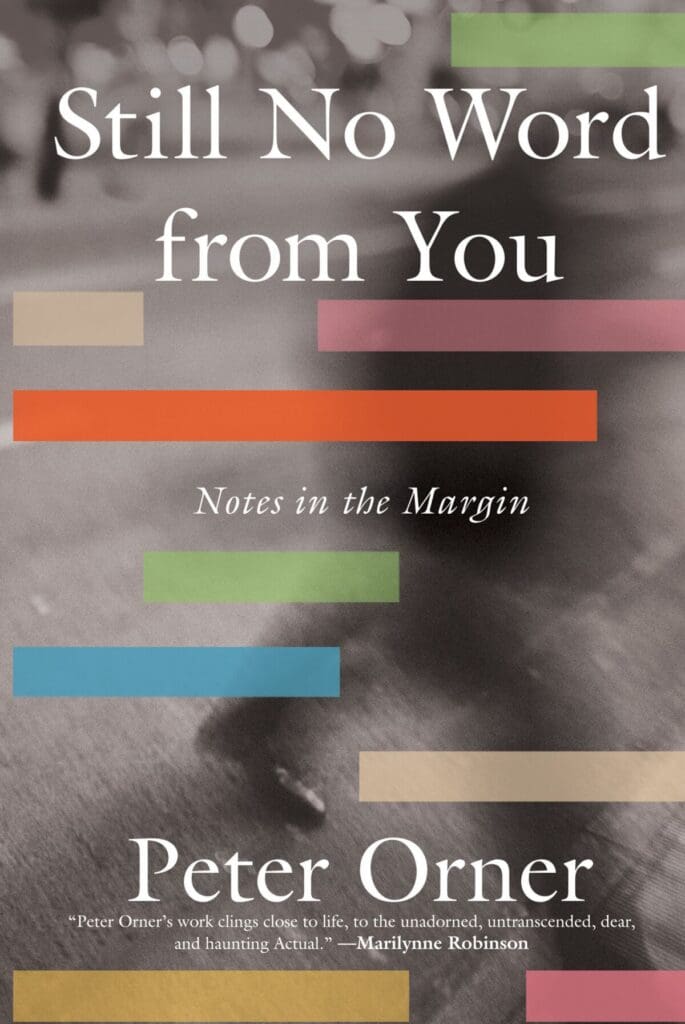

Paul Wilner, Past Contributor: If you’re feeling autumnal, but don’t have a stake in the October Classic (with local favorites sadly eliminated), check out Peter Orner’s meditative essay collection, Still No Word From You: Notes in the Margin. The former S.F. State professor—now creative writing director at Dartmouth—offers deeply read takes on everything from Lorraine Hansberry’s neglected play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, to his mother’s secret passion for Ferlinghetti, and Herb, his father’s electrician, who shows up unexpectedly for his funeral like the mourner at Gatsby’s lonely ceremony.

Keeping with the baseball theme, Emil DeAndreis’ new novel, Tell Us When To Go combines the tale of a college pitching phenom who develops a bad case of the yips with a vivid portrait of the inequalities of present-day San Francisco and Silicon Valley. Arresting.

And Christine Sneed offers two salient perspectives: Please Be Advised, a novel in memos that should hit home for anyone familiar with the insanities of corporate “culture,” and Love In The Time of Time’s Up, a tart, smart anthology dissecting the sad state of interpersonal relationships. Contributors include Victoria Patterson, Karen E. Bender, Joan Frank (who has two new just-released books of her own, the essay collection, Late Works, and a novella, Juniper Street), along with Sneed’s own story, “Potpourri’,’ and Elizabeth Crane’s laugh out loud response to online dating jerkiness, “Dudes, In Theory.’’

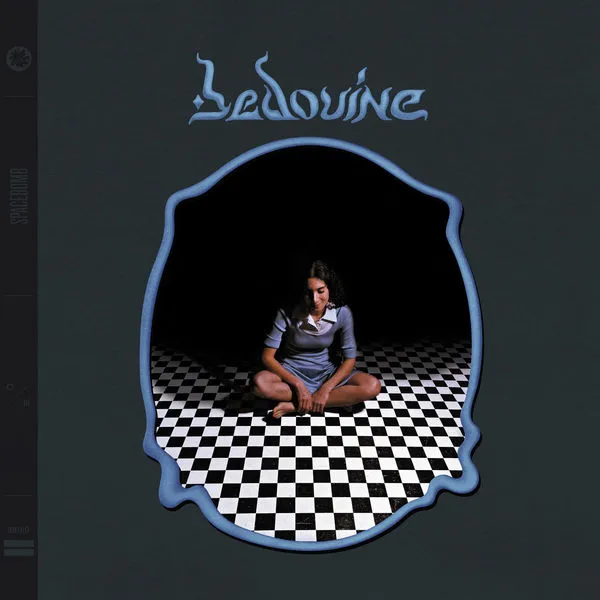

Isabelle Edgar, Intern: I don’t often like new music. I would have done well in the 60’s or 70’s, I think. But a few years ago, I found a modern day Joni Mitchell (or perhaps a more of a modern day Leonard Cohen). Azniv Korkejian performs under the name the stage name Bedouine; she makes music that sounds like a love letter—to someone, some place, or to oneself. Bedouine moved around a great deal as a child, growing up in Syria to Armenian parents then arriving to the U.S to live in many different cities, and as such her work has a potent and honest sense of nostalgia, a feeling of remembering—and perhaps missing—something from the past. She has a certain tenderness infused in all her work. Her music feels personal, cared for, and unwaveringly individual.

This is not music that is trying to “prove itself.” There are no bells and whistles, and the songs are often simply comprised of Bedouine and her guitar. Her music feels like the lamp is lit low, and the air is warm and humid. I saw her perform a few months ago in Santa Cruz, at the Kuumbwa Jazz Center, where the seats are so close together you can feel the shoulders of the person next to you, and where nearly everyone has a glass of red wine. Bedouine he sat on a stool next to fellow musician Gus Seyffert, a single spotlight on them, sipping her own glass of red wine between songs as though it was water. Bedouine talks just like she sings. She is poised, eloquent, and captivating.

“I am not an island, I’m a body of water.”

This line is from her song “Solitary Daughter,” a conversational song that reminds me of Leonard Cohen’s “Chelsea Hotel” or “Suzanne” in its specificity and storytelling. In this ode to loneliness, Korkejian writes, “I play with the moon, my only friend. It pushes and pulls me. I don’t pay rent. I don’t need the walls to bury my grave, I don’t need your company to feel saved.”

I appreciate Bedouine’s music for its simplicity. My favorite of her songs is “Nice and Quiet.” She expresses intimacy not through flowery language, but by saying simply, “I will try my best to keep my head nice and quiet for you.” Since the language is simple, it can be read in many different ways and can connect to many different people as most of us know the feeling of trying one’s best in some way for another. There is an agelessness in her vulnerability that is quite rare.

Bedouine has three full albums: Waysides, Bird Songs of a Killjoy, and her self-titled album, which is her first and my favorite (the aforementioned songs “Solitary Daughter” and “Nice and Quiet” are on this one). I return to it often because it is honest and beautiful in an unadorned way.

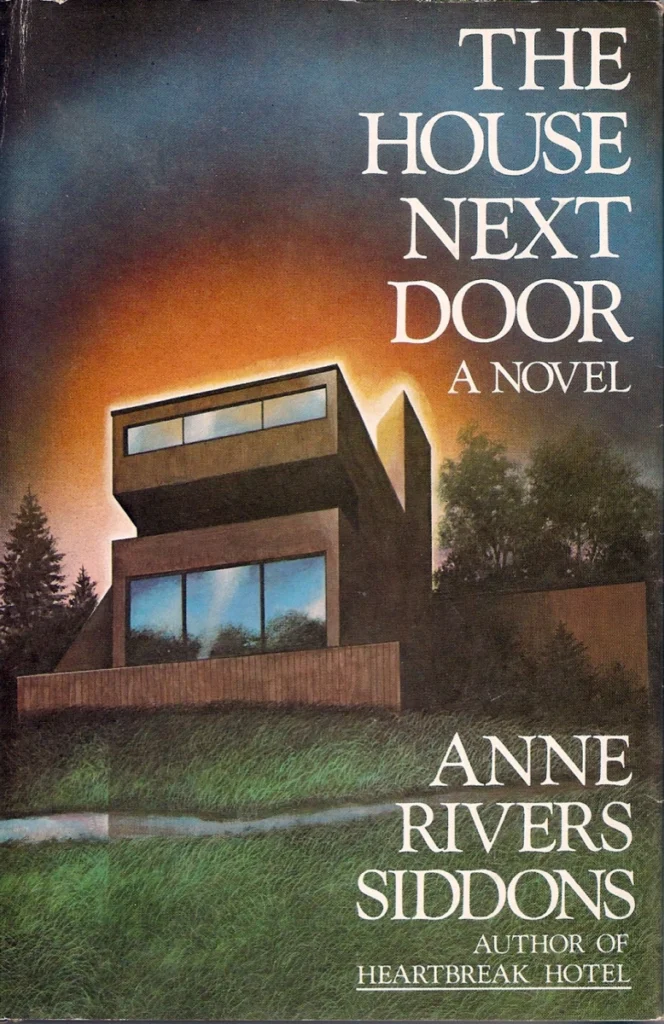

Zack Ravas, Assistant Editor: The Seventies saw several of the horror genre’s classic tropes, those cobwebbed and gothic conventions from centuries past, brought into the modern era: Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot updated the vampire mythos for the working class, while Anne Rivers Siddons’ novel, The House Next Door, transplanted the ‘haunted castle’ tale to a well-to-do neighborhood in Atlanta. I’d long heard praise for Siddons’ novel coming from the likes of King himself, but decided to finally crack its pages this Halloween season; I was immediately pulled into the narrative from the prologue, which goes to great lengths to convince the reader that the people telling this story are as unassailably “normal” as you or I, and therefore are not exaggerating about the paranormal occurrences that are about to unfold. “Our friends are going to think we have taken leave of our senses, and we are going to lose many of them,” protagonist Colquitt Kennedy warns. “For the Harralson house is haunted, and in quite a terrible way. And it is up for sale again.”

The point-of-view of this novel offers two fresh conceits: one, the house in question isn’t some ages-old manor where some past misdeed has created ghosts, as you might expect, but a brand new and beautifully modernist home designed by a hotshot young architect; and the story isn’t told from the perspective of the family residing in the house but rather the childless married couple who live next door. This creates an voyeuristic element of ‘Keeping Up with the Joneses’—we often can’t resist peeping over the fence to catch a glimpse of what’s happening in our neighbors’ lives, but what happens when we are then witness to mental instability and death? And how much “bad luck” and tragedy would have to befall different neighbors who purchase the same house before you began to suspect something supernatural was afoot?

Siddons’ book remains fresh because the supernatural force at the center of the Harralson house doesn’t unleash demons or possessed dolls but attacks at the very heart of human weakness; it finds whatever crack there exists in its occupant’s life—the absence of a parental figure, martial weakness, the trauma of losing a child—and exploits it to malevolent effect. The problems the occupants of the Harralson house face are not out of the ordinary, which creates both a sense of realism to The House Next Door as well as a lingering question: is it the neighbors who are mentally unraveling the longer they stay in the house next door…or is it our work-from-home narrator who is unraveling the longer she voyeuristically stares out the window? Anne Rivers Siddons’ novel is my recommendation for a book-I-couldn’t-put-down this Halloween.