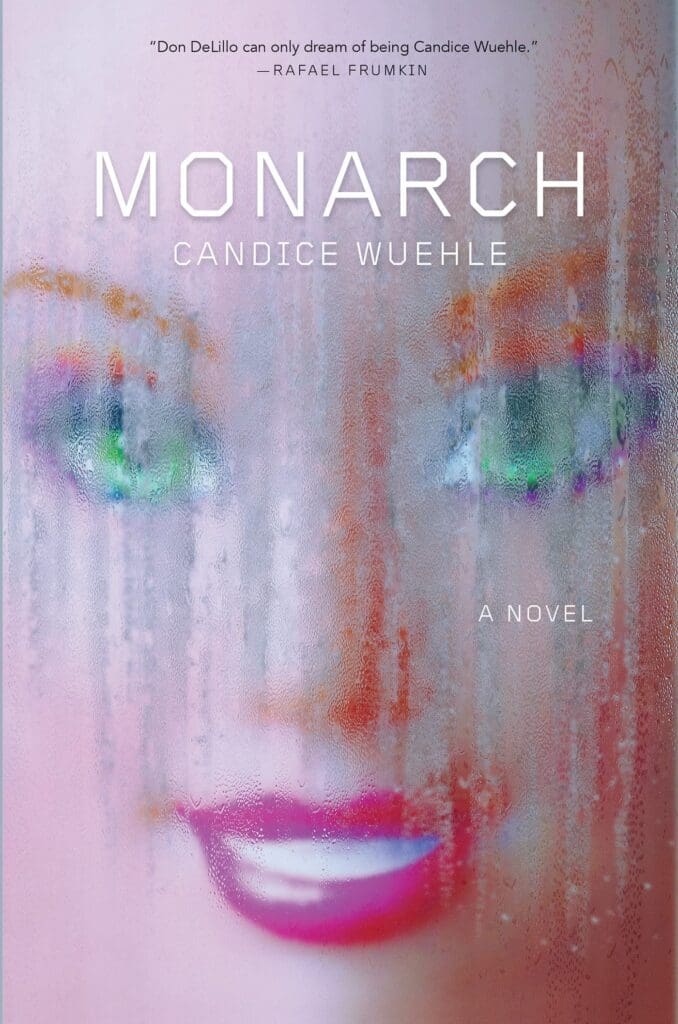

Candy-coated nightmare is a familiar aesthetic by now. From TV shows like Stranger Things to movies like Birds of Prey, it is not unusual to see horror and violence shellacked in bright colors. Monarch (256 pages; Soft Skull), the first novel by acclaimed poet Candice Wuehle, wears the neon skin of such blockbusters while exploring much thornier intellectual territory, asking: what is the true meaning of self?

On the surface, Monarch is a thriller, charting the life of former beauty queen and decommissioned clandestine operative Jessica Greenglass Clink. A child pageant star from the age of four, Jessica grows up shaped by the ambitions of her Norwegian mother, Grethe (herself a former beauty queen), and the disinterested supervision of her father, Dr. Clink, an academic specializing in Boredom Studies. Eventually, Jessica’s horizons are broadened by an inexplicable babysitter, the goth punk feminist Christine, who teaches our narrator to love Joy Division and to question anything that reeks of conformity. When she’s around thirteen, Jessica starts to come into herself—she falls into love with another erstwhile beauty queen and quits pageants entirely. Yet for the next four years of her life, she remembers little, apart from waking up with strange bruises and an unpleasant taste in her mouth.

Those mysterious years are what powers the book’s plot. Everything proves connected, from Jessica’s sinister mentor Chancellor Lethe (yes, the name is an apt reference to the river of forgetting) to her weird roommate during her brief stint in college to Grethe’s habit of selling anti-aging devices to other beauty queens. After a disturbing incident sends Jessica on a search for her true identity, the novel cues up a whirlwind of disguises, tracker chips, flights around Europe, and handguns hidden in the back of fine silk dresses.

While the pop culture framework of Monarch is easily comprehensible, the true essence of Wuehle’s bookis anything but. Beneath the trappings of shadow governments and impeccably-coiffed murder is a pulsing search for identity. As Jessica tries to find her “original face, the one [she] had before [her] parents were born,” the novel pushes the reader to interrogate their own pursuit of self-knowledge. Invoking sources both scholarly and mainstream to undergird Jessica’s hunt for self, Wuehle seems to be asking what it actually mean to know oneself, and whether it is even possible.

Monarch’s clever strangeness is illuminated by Wuehle’s background as a poet. (Her , collection Death Industrial Complex was shortlisted for the Believer Book Award in 2020.) In a recent interview, she said Monarch began as a prose poem, inspired by a theory that JonBenét Ramsey’s mother was a Deep State sleeper agent who was accidentally triggered and therefore killed her daughter. While the project grew into a complete novel, its origins as a prose poem are traceable in the unsettling imagery and the narrative’s recursive obsession with itself:

So far this story has been a study in circles, but by the end of this chapter we will finally be ready to start talking about spirals. We will become more confident, more violent, safer than ever before. Our story will start to curl outward into time; I’m saying we will be an anti-pearl, I’m saying we will stop being slugs and start being snails; I’m saying we will finally leave the ‘90s with a corkscrew in one hand.

Almost a hundred pages later, Jessica revisits this metaphor:

Finally, though, this is becoming the story of the spiral that I promised you it would be. Now that we have obliterated the origin, this is the story of the curl that becomes more deadly with each rotation away from its root.

Nestled within such self-referential reflections are a series of haunting oddball scenes. Wuehle has a gift for such snapshots, such as two scintillating glimpses into Dead Ringers, a fight club conducted in the dead of night by the teenagers of Jessica’s Midwestern suburb. Similarly unforgettable is Jessica’s memory of her father saying “I love you” by flashing his Chrysler’s headlights in Morse code—the only way he is ever able to say those words. Later, Wuehle turns the snowy peak of a mountain outside of Bergen into a metaphoric Yggdrasil, the sacred tree of Norse mythology uniting the underworld with the heavens.

Monarch is a novel of ideas welded to the structure of a page-turner. Wuehle destabilizes the reader, in the same way her protagonist is destabilized for much of the novel, through careful attention to form and a dense cosmology of references. And though Jessica genuinely experiences a fractured self because of abuse, her story echoes the more mundanely damaging experiences of young women molded by rigid perceptions of femininity. It becomes easy to root for this traumatized teenager, even when she begins to wield the terrible violence hidden inside her. Darkly comic, cynical, thought-provoking, and strange, Wuehle’s novel is a rare offering.