Imagine for a moment that the power to your city has been turned off for an undisclosed amount of time—a precautionary measure to ensure that homes are not engulfed in flames by the fires that rage just outside the city limits. A heat wave invades the city and in the darkness of a blacked-out night, no air conditioners hum. People open their windows to let in air, any air, to cool themselves amid the scorching heat, even if it is full of smoke from nearby fires. The state has issued water restrictions due to drought and, oh yes, people are still expected to go to work because the state can’t risk shutting down the economy just because natural disasters encroach from every corner.

If you live in California, this image is not hard to conjure. And in her second novel, set in a dystopic, near future Los Angeles where fires burn, celebrities are worshiped, and water is purchased on the black market by those wealthy enough to afford it, Alexandra Kleeman depicts such a conceivable if incredible landscape of catastrophe.

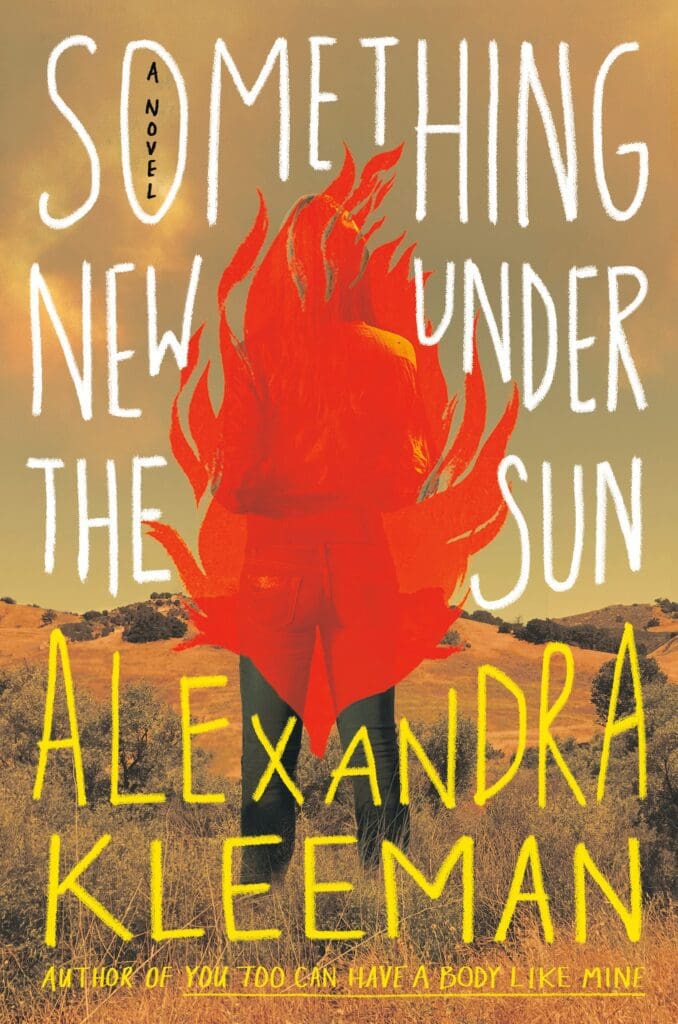

Something New Under the Sun (368 pages; Hogarth) is a noir-inspired satire that follows East Coast novelist Patrick Hamlin as he ventures to Hollywood to oversee the film adaptation of his most recent book. He is hopeful this will be his family’s ticket out of a bleak existence back east where his wife is tormented by climate anxiety. The only trick is getting his wife, Alison, and young daughter Nora to actually join him. Upon arriving, he quickly discovers Hollywood isn’t everything he was promised it would be.

For starters, Patrick hasn’t exactly been flown out to consult on the script. Instead, he’s been assigned to work as a production assistant—a “job for a kid,” as his wife points out to him. And it’s true, his fellow production assistants, Horseshoe and the Arm, are a couple decades his junior and reek of a particular over-educated-under-ambitious-stoner-conspiracy-theorist breed that feels very California millennial. As Patrick gets acquainted with the world of movies, their voices act as a sort of postmodern mixtape of ontological witticisms. Patrick’s main job, as it turns out, is acting as chauffeur and babysitter to the film’s leading actress, Cassidy Carter—a starlet known equally for her childhood television roles, public displays of belligerence, and perfect nose (which brings in royalty checks from plastic surgeons every time they alter the nostrils of everyday women to resemble Cassidy’s).

Patrick’s days are split between carting Cassidy around and running errands to various WAT-R facilities for the producers. In California, WAT-R is the new water, and actual water is scarce. The public doesn’t seem to question the disappearance of real water because it has been replaced, improved upon, and designed with everyone in mind through varying lines ranging from “pure” to “deluxe.”

Back home, Alison’s obsession with the climate crisis grows despite Patrick’s insistence that everything isn’t as dire as it may seem. In a phone call she says,

“I look at Nora and I know there’s no future for her, and it tears my heart in two. And what makes me feel crazy is that all around me, everywhere, people are driving cars and buying propane grills and eating double cheeseburgers, and not one of them sees what I see, and that means we have no chance.”

Shortly after, she takes Nora to Earthbridge, a mysterious eco-cult where each morning members mourn the loss of living creatures decimated by climate change. Despite the fragility of his family, Patrick stays in Los Angeles if for no other reason than “that he doesn’t want to give up a nothing that could become something glamorous for a nothing that’s certain to remain so.”

Kleeman’s L.A. is as surreal as the L.A. of Pynchon’s Inherent Vice. Similarly, there is a distinctly drug-induced vibe that permeates the pages. But for Kleeman, it isn’t the irreverent outcast that’s imbibing, it’s the general public and they don’t even know it. Nothing is as it appears, including the movie Patrick is working on. And like a Pynchon novel, Something New Under the Sun is concerned with fallacies of truth. But Kleeman’s question seems less about whether finding an objective truth is possible and more about the nature of truth through collective seeing.

“You only needed one other person to see what you were seeing in order to make it real: two people seeing the same thing, in fact, was more real than a whole roomful of people seeing it and sneering.”

At times the novel veers heavily into the philosophical and can feel a bit removed from the emotional stakes of the characters, but just when the book seems as if it will stray too far into the conceptual, Kleeman pulls us back in with a moment of humane insight.

What is most compelling about Something New Under the Sun is how Kleeman has juxtaposed eco-radicalism beside climate catastrophe and shows the irony that even in a world gone up in flames, the radicals still appear unhinged compared to the pacified masses. Ultimately, the novel begs the question, is something truer simply because more people say it is?