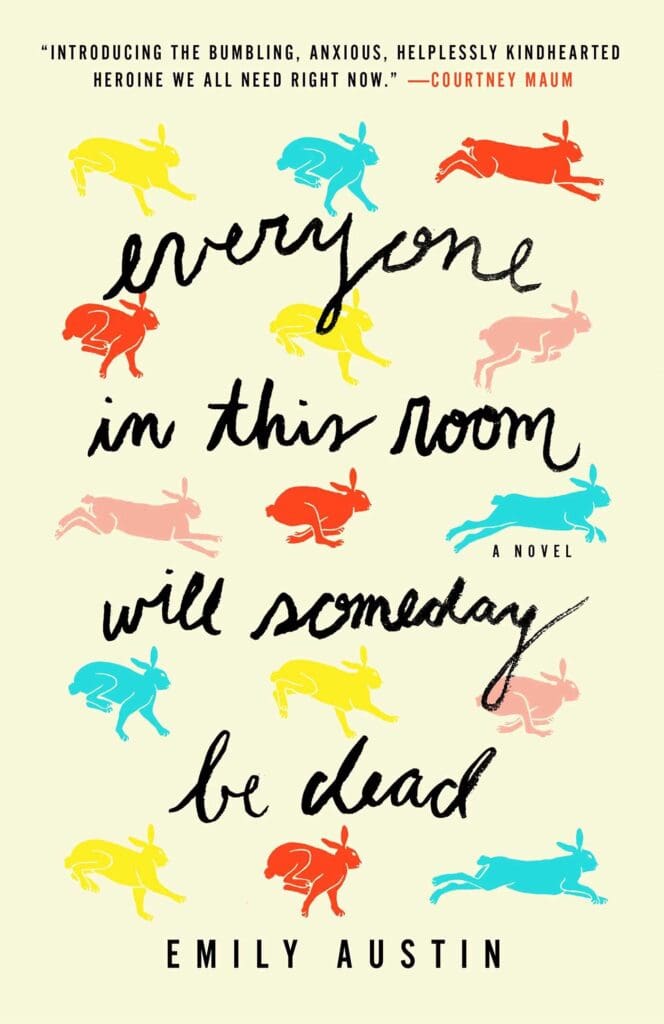

Life is, as some are already too aware, absurdly fragile and relatively meaningless. This certitude saturates nearly every page of Emily Austin’s debut novel, Everyone in This Room Will Someday Be Dead (243 pages; Atria Books). Though the book’s title makes it fairly clear what is to follow, its cover, with its delicate cursive lettering and pastel bunnies, might mislead one to expect an ultimately lighthearted or uplifting story. This is not the case. Readers should go in with a few warnings: the novel is fundamentally about severe anxiety and thus severely anxiety-inducing; it contains heavy suicidal ideation and is altogether a depressing condemnation of human life. However, the narrator, Gilda, is a hilarious and compassionate overthinker whose musings oscillate between eliciting full-body laughter and profound hopelessness. Through Gilda, Austin pulls off the difficult task of bringing humor to the bleak, enduring, and incessant lesson that every life will someday end and, in the grand scheme of things, could just as well have never begun in the first place.

As the book opens, the narrator is fired from her previous job at a bookstore because she frequents the hospital more than she shows up for work. Gilda, despite being an atheist lesbian who lies most times she speaks, soon winds up as an administrative assistant at a church. Imposter syndrome inevitably follows, although she rejects this notion because she can’t even wrap her head around the concept of being anything. “How could I be a bookstore clerk, or a Catholic, or a woman, or a person at all?” Questions such as these continue to arise as she struggles with the dissonance between being a different person as an adult than she was as a baby, despite possessing the same hands, the same physical existence. During one of her many visits to the ER, the doctor asks why she’s come in and she responds, “I just can’t believe that there is a skeleton inside me.” Her body vexes her: a “meat sack” with chemicals that result in something called feelings, a vessel that will soon become a corpse, which someone else will have to deal with and which garbage will outlast.

Gilda obsesses over death, be it her own or a stranger’s, so when she finds out that the woman who preceded her at the church died mysteriously, she copes with her discomfort by impersonating the woman via email and launching an investigation. Though her actions are often bizarre, it is difficult not to love Gilda as we are subject to her every thought and emotion, whether she is deciding that a woman flirting with her must actually be trying to steal her identity, or punching her mirror because she thinks her reflection is an intruder, or liking inappropriate pictures of women’s butts from the church’s Twitter account, or even contemplating jumping off a bridge. Austin creates a strong cast of characters and develops them skillfully, introducing fictional people that would be recognizable in the real world: a father with disappointment and anger issues, a priest wrestling with grief, a lonely old woman seeking comfort in an old friend, and a younger brother in emotional turmoil hidden by an unaddressed drinking problem.

Animals reappear thematically throughout the novel as Gilda ponders their behavior, their bizarreness, and their simplicity. She constantly likens them to humans—because really, what’s the difference? Surely not their significance. As she is tortuously aware, people matter just as little as the lost cat in her neighborhood or her dead childhood rabbit—each is just a tiny, imperceptible blip in the enormousness of space and time. However, she also spends a paragraph near the end of the book marveling at rhinos, dubbing them magical creatures. Although she doesn’t directly afford humans the same diagnosis, later on, while deep in a depressive episode, she remarks that humans are indistinguishable from animals, as if this should be an insult. She can see animals as wondrous, but even in equating them with humans, with herself, the chronic negativity that comes with her illness prevents her from seeing the beauty in this comparison.

Austin has an impressive ability to portray disordered thinking, demonstrating through first-person narration how someone can completely spiral without even noticing. For readers who have experienced depression and anxiety, Austin presents something resonant and validating. Even for those who have never felt Gilda’s emotions or would never do what she does—such as impersonate a dead woman rather than inform a friend of her death, or consider ending her life—the book is tender and insightful. Though most of what goes on in the church baffles Gilda, they seem to get one thing right: “Remember: you are dust and to dust you will return.”