In Ghost Forest (251 pages; Random House), the novel’s title is also the name of a painting created by the protagonist, an unnamed daughter of immigrants from Hong Kong. As an adult, the narrator takes her father, who throughout her childhood split his time between Hong Kong and Vancouver, to see her painting in a juried show. “In the painting, I am riding a brown bird,” she describes. “We are soaring above tree after tree, and each one is white and translucent. I washed white watercolor on gray rice paper to create that effect.”

Her father’s reaction is not what the reader expects: “Without looking at me he said, I think there is something wrong with you that you’re making art like this.” Her father continues to view the show, and she follows in silence behind him.

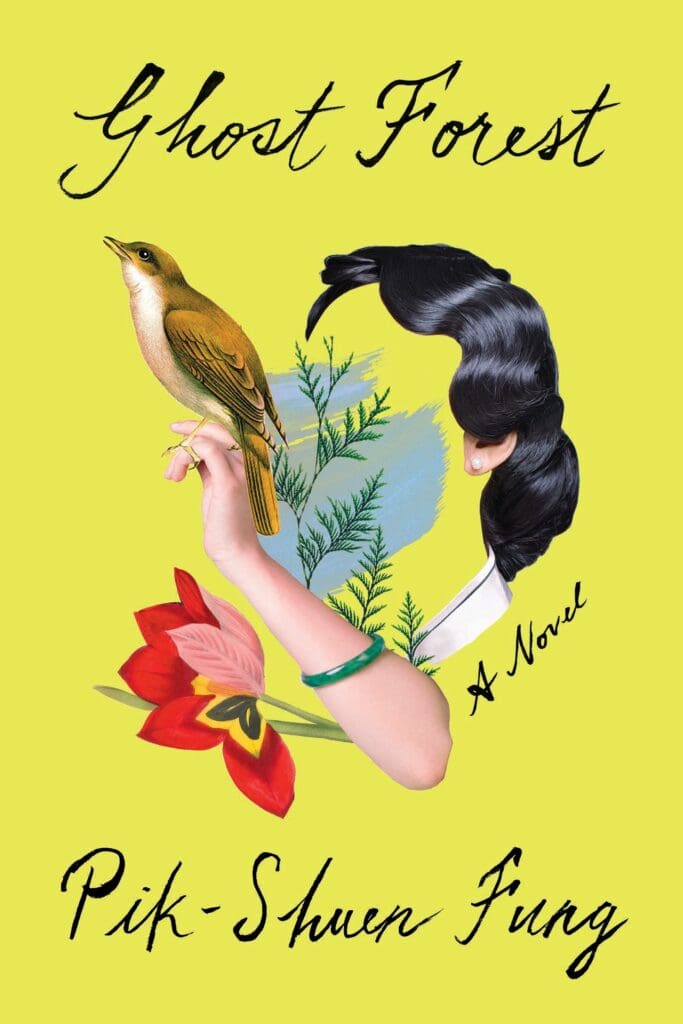

Ghost Forest’s author, Pik-Shuen Fung, is an artist as well as a writer. Her first novel’s brief but poetic chapters are both visual and lyrical, encircling readers in a story of lineage, place, and familial love. As the father becomes increasingly ill, the novel further explore the family’s immigration from China to Canada, as well as her experience attending a university in the United States and visiting her bedridden father in a hospital.

What do you say to someone who is dying? Perhaps it’s what we don’t say enough to the living: I love you. Yet the protagonist—artist, daughter, Canadian-born, American-educated, Chinese and straddling many cultures—has to practice offering and receiving the words. First, readers are told a memory in which she says, “I love you” and her father responds, “Thank you!”

Again, another memory: “I love you, I said. There was no answer. I didn’t know if he was asleep. I walked back to my room and plopped facedown on my bed.” She keeps trying, forming the words, demonstrating tenderness to her father so she can receive it in return. It’s work for him, explicating the universally true—that parents love their children—because saying the obvious out loud can feel silly. But the words are so vulnerable to doubt, we are so vulnerable to doubt.

She tries again: “I love you, I said. He looked back at me, eyes blank. We’re Chinese. It’s not important for us to express our feelings. Underneath this sky, all parents love their children.”

Her mother takes a different approach: it’s not that saying “I love you” is redundant, it’s that offering the words sparingly maintains their integrity. “All those western people, my mom said over the phone, they use the word love for everything. They say it like they say hello.”

The writing of Ghost Forest mirrors the protagonist’s xieyi painting, a style wherein the brushstrokes draw attention to themselves and the whitespace around them. What is present is as important as what is not; fullness is not so different from absence, and absence or white space draws attention to what is there, creating balance for each other. To read Ghost Forest through the lens of the main character’s art means to understand that sometimes a limitation of words can draw out emotion more effectively than access to unlimited words. Ghost Forest and the protagonist’s experience of her parent’s I love you’s is a lesson in precision.

“What were you like when you were a kid? What are the things you wish you’d known? What makes you sad? And what makes you happy?” the narrator reflects at one point. She seems to understand that loving someone is not the same as knowing them; family implies love though family does not imply knowing. While they’re still here, she says the most important thing: I love you.