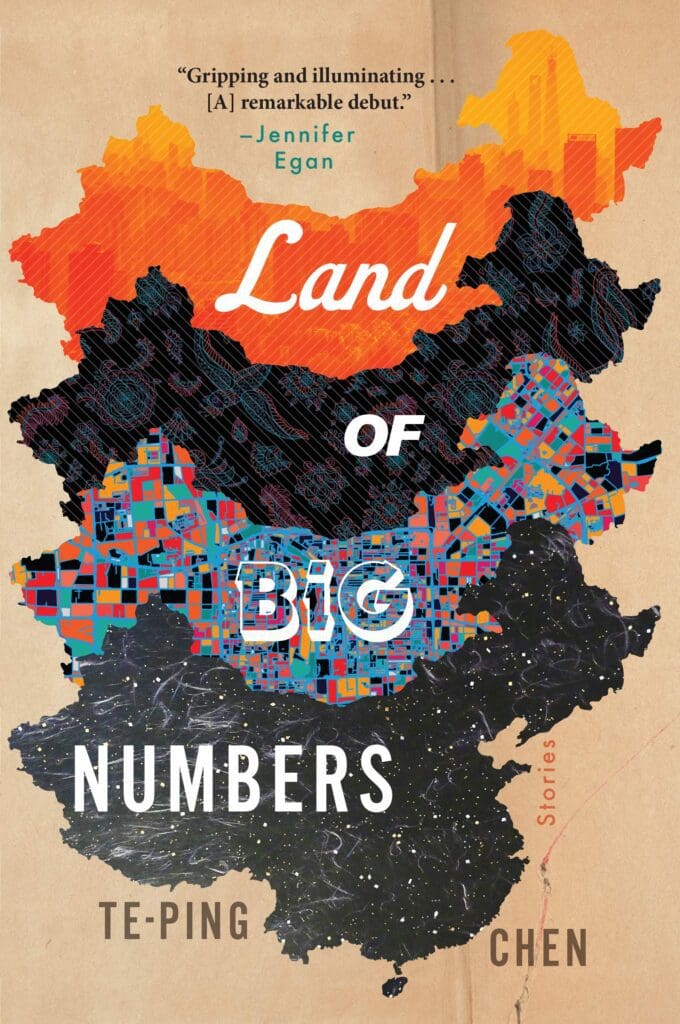

To the rest of the world, China often looks like a monolithic, vast “land of big numbers,” where its people are eclipsed by the country’s monstrous economic influence and the Communist Party. But in her first story collection, Land of Big Numbers (255 pages; Mariner Books), journalist and fiction writer Te-Ping Chen gives breath and form to those who may be overlooked. Written during Chen’s time as a China correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Land of Big Numbers is a literary simulacrum of modern China and the agency of its people. Here, each fictional story holds a mirror to a national reality.

Te-Ping Chen is especially invested in marginal characters who move defiantly between the cracks of the system. The collection begins with a pair of twins in “Lulu,” in which one twin becomes a professional gamer while the other becomes an online political dissident. While the story is an intimate recount of the fraying bond between siblings, it also alludes to the complicated duality of the Internet as a platform for both individual expression and political censorship. In “Flying Machine,” an ambitious but poor farmer desperately tries to impress the village party secretary by building an airplane out of junk. The airplane won’t fly, and neither will the farmer’s utility as an archaic, working-class nobody. Yet he never stops inventing. “Next time,” he repeats with increasing fanaticism.

Even while grappling with social critiques, which often can veer into cynicism, there is a surprising buoyancy to Chen’s stories. Combining her journalistic acumen with her skill as a storyteller, she brings readers otherworldly joy in “New Fruit,” a story about a new strain of fruit that exposes a rural village’s cultural amnesia and transforms the lives of those who consume it. Seasons of this superfruit allow villagers to ask for forgiveness and to repay past debts: “old men and women in the street with tears in their eyes, embracing or eating pieces of the qiguo as they traded recollections: the mother whose hair had gone white overnight, the belts we had used on our victims, the temples we had defiled.”

In some ways, Chen’s stories are so real they seem prophetic: in the title story, Zhu Feng invests earnestly in the stock market, addicted to his short-term gains, “new money” rewards, and to a faith that the economy will only grow. Reminiscent of the recent retail investors’ challenge to the power of hedge funds, Te-Ping Chen presciently captures the ways ordinary people are contending with rigid power structures. (It feels like only a matter of time until we see further echoes of her stories appearing on front pages.)

As a collection, Land of Big Numbers is a bold achievement in both the breadth of its themes and the precision of its details. It is an ambitious undertaking for sure, spanning borders and chronologies, and narrators of no one common biography. Still, Te-Ping Chen anchors us by providing unexpected solace through stories that celebrate how the strongest of human impulses is to preserve the freedom to act.