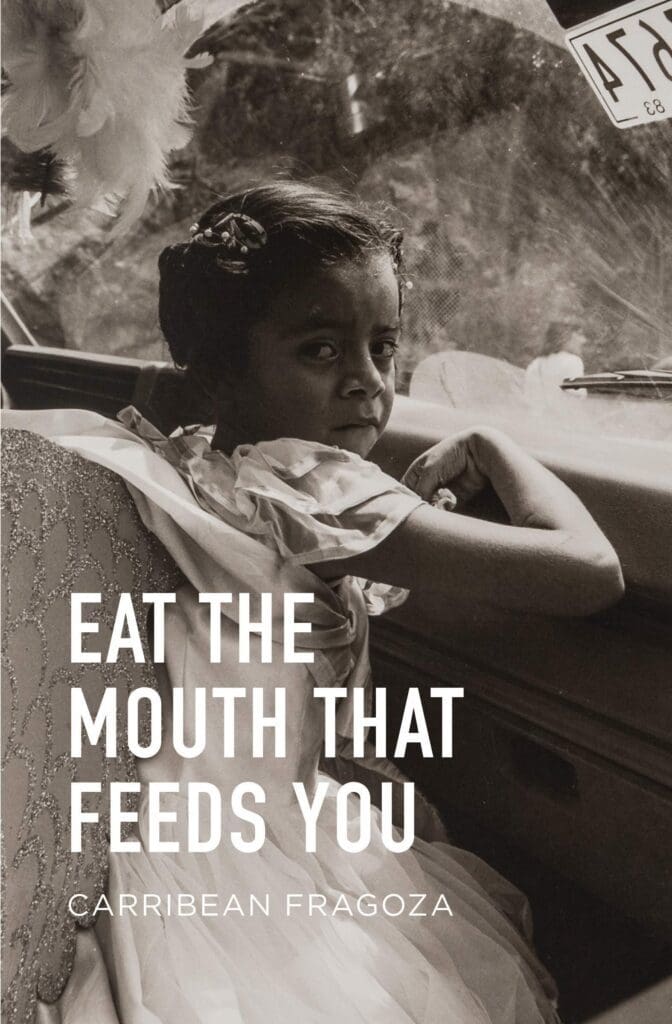

Carribean Fragoza’s debut book of fiction, Eat the Mouth That Feeds You (144 pages; City Lights Publishers), is a collection of supernatural, almost mythical short stories. Set in Fragoza’s home town of South El Monte, a suburb east of Los Angeles, the collection explores what kind of violence is exchanged intergenerationally and what happens when the resulting wounds are not attended to. Fragoza’s characters, all of whom are Chicanx or Mexican women, explore the many worlds of their bodies, minds, and lineages.

Carribean Fragoza recently spoke to ZYZZYVA via Zoom about Eat The Mouth That Feeds You.

ZYZZYVA: The first story in the collection is one of childhood and upbringing while the final one, “Me Muero,” is a story about death. In that sense the book itself has a body and a life cycle. Was this intentional? How does your mythological approach to storytelling impact your relationship with form?

CARRIBEAN FRAGOZA: The structure was intentional. My editor and I worked on it together, looking at all of the stories that I had written over a decade. In addition to thinking about an actual life cycle of a person I was also thinking about what it means to come to terms with all of these complexities and difficult aspects of Latinx life and of being a Chicana, a child of immigrants, of being a woman. There’s the part of me coming to terms with the different violence that we grow up with and that we live with as adults because we’ve internalized so much. What do we do with all of these wounds that we carry? There has to be healing and strength-building.

I really think about what questions I’m trying to pose to the reader as they’re reading through the collection, and one of them is looking to the future. How do we build a new society, a new way of living and being that won’t repeat these cycles of violence, and how can we start to imagine a new world? How can we think outside the boundaries of what is just real and what we understand to be real? I gravitate toward the mythological because mythologies are ancient, but they also exist in these stories that we’ve inherited over thousands of years and carry today. Mythologies defy our notions of what reality is and what is possible.

Z: The title of the book is also the name of one of the stories; a shorter piece about intergenerational knowledge and connection through literal consumption of the body. At the same time, your work centers stories of Latinx and Chicanx women and girls, mothers and daughters. The social consumption of women is a kind of misogyny, but in your story the consumption of girls is a means to fusing generations together. Can you talk about this tension?

CF: One of the things that I was thinking about as I was writing [the story] Eat the Mouth that Feeds You is how sometimes trying to learn about our family history and extract stories from our mothers and grandmothers can be a kind of violence. Just because you’re ready to ask these questions doesn’t mean you get to have the information. At the same time, it is very important to learn about why we are the way we are—that was an interest that I’ve always had: why am I the way I am? Why do I behave the way I do?

I was thinking about that and the daughter character being so insistent and aggressive with her mother. But then in turn the mother tries to think about her own mother and starts to reflect on her path. There is that component of violence as well in the process of healing present between generations of women. I’ve heard this from the children of refugees or survivors of genocide that have tried to talk to their parents about their experience of survival, and sometimes it’s impossible to access that place of pain. That was something I was thinking about when writing my story.

I was a Chicano studies major as an undergrad at UCLA. A lot of Chicano studies is about learning our history, about different struggles and movements, and about learning our ancestors. There are these big overarching narratives that you learn, and you think, oh, that’s, that’s part of me, which is true. But getting down to the nitty-gritty of the family unit and of your own personal lived experience, those broad narratives become a lot more complicated, and I think they’re often left out from discussions about history.

Z: At multiple points in the collection, such as in “The Vicious Ladies” and “Ini Y Fati,” your characters say, “We look after each other.” The characters who hear this still seem to feel alone, however; why is this? What is the role of community care in your stories?

CF: The idea of how women and how girls look after each other is a really important question for me because I really believe that we’ve not been protected in all of the ways that we’ve needed to be. Even if we have had totally loving parents—which I did have growing up—we may not have protection in the outside world because we still live in a patriarchy and there’s still a lot of extreme violence toward women and girls. Still, a lot of the violence that we’ve learned and that we’ve experienced has happened at the family level. Then, I tried to think about how women and girls can protect each other because only we know what we really need; we cannot rely on men or other people outside of us to really understand what those needs are.

Though the protagonists find an important sense of companionship and support from the other female characters, there’s still some other kinds of violence and abuse that’s taking place within those spaces. There are these conflicted relationships with “the other” and with this sense of community that embraces you but can also be oppressive if it ignores the wholeness and humanity of each person. I was thinking through how, even in the spaces that are supposed to be safe and empowering, there’s a danger of replicating a lot of these patriarchal notions of what power is supposed to be and how we’re supposed to enact it in the real world.

In “The Vicious Ladies,” the main character really admires and is simultaneously drawn to and repelled by Samira, the leader at the party scene. Samira is kind of a big bully, though she has this amazing vision for female solidarity and for ways that grown women look after each other. Yet, she disregards the main character’s interest and doesn’t really listen to her. There’s this desire from the main character to be seen and Samira does and she doesn’t. The main character really struggles with that. Similarly, for “Ini y Fati,” the main character respects and admires the young virgin character to a certain extent. The young girl really does admire Ini, but the little child virgin saint is also kind of a cruel little being who has no qualms with inflicting violence.

Z: The collection seems to grapple with the space between life and death, a sort of middle world. What is magical about that space? What stories are made possible by being not fully alive yet not really dead?

CF: I am really interested in that sort of middle, living-but-not-living place. A lot of my characters are burdened by their history, but they’re also animated by it. Even if it’s not something they can articulate or understand yet, there’s still this compulsion to do something. I guess I feel that way in myself and in my own body. In “The Vicious Ladies,” my main character is having a hard time belonging to this party crew. She hates it and she loves it at the same time, and she still has this drive to get up and hustle. My main character in “Me Muero” is dead but she still feels compelled to get up and look around and engage and she needs to do something even if she doesn’t totally understand what that is.

Z: The Los Angeles region is the backdrop for many of the stories. What does L.A. mean to you?

CF: Most of my stories take place in some version of South El Monte because I was raised there. The suburb was one that was really infused with industrial zones, and it’s also right up against natural spaces like the San Gabriel River. It’s a very peculiar place in the sense that it’s a suburb, so that sort of strays from the common notion that Chicanos live an urban reality or something, but I grew up with a totally suburban experience. My mom was a homemaker and my dad was a truck driver. The suburbs that I grew up in are not the kind of suburbs that you see on TV. They’re not the white middle-class suburbs. They’re poor and working-class people of color, multi-ethnic, Mexican, Mexican American and Southeast Asian, Vietnamese and Cambodian.

I’m not the only author that has written about this place; luckily there are other writers who came before me, like Salvador Plascencia, Michael Jaime-Becerra, and Toni Plummer. There’s something about this place that really feeds our imagination and provides a fertile background. I’m a strong believer in place-based writing, and to me that means the places will tell you the stories. It’s not necessary, and maybe not correct either, to come in and try to tell the story about a place when the place has its own stories. The stories are there, and it’s our job to listen to them.