Consciousness. One of science’s big questions. What is consciousness? But we have been writing consciousness for thousands of years now, and one of America’s most miraculous writers has just given us a second collection of essays so brilliantly perceptual that the writing is—for all intents and purposes—neurological. The visual tapestry is so vivid, so rich, one forgets one is in the medium of language. Take almost any image or detail in a Jo Ann Beard piece and follow its pathways, its firings, its bright illuminations, its quieting into a kind of shade thrown across the entire essay—it is a map of a brain in action. If one grandmother has chickens in her yard, another grandmother has “her own gentle version of hens and chicks: cunning little succulent plants that spread in a low green flock across the cracked dirt by her back door.”

The writing never forgets the myriad connections a brain makes, or that time within a mind is elastic, richly simultaneous, far more intricate than chronography—which is its own metaphor—ever suggests. In “The Tomb of Wrestling,” Joan, who has just had her nose broken by an intruder into her home, thinks that “something weird was happening to time—it was swirling instead of linear, like pouring strands of purple and green paint into a bucket of white and giving it one stir. Now was also then was also another then.” This is a good description of how Beard moves one perception within another within another, and does it with perfect clarity.

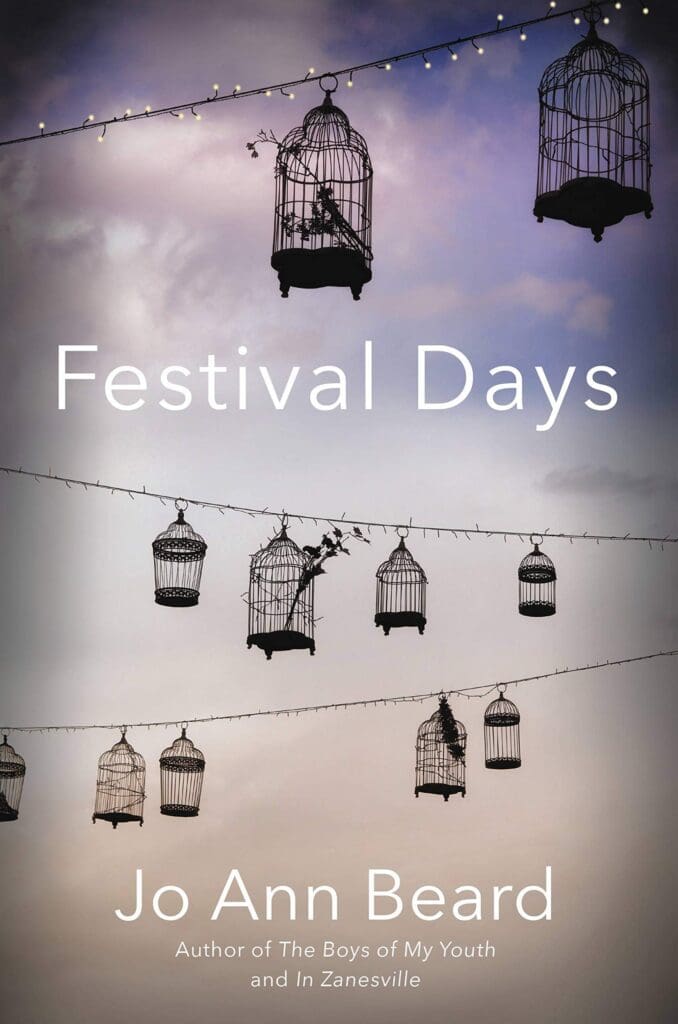

Festival Days (272 pages; Little, Brown) collects essays, already famous essays, such as “Werner” and “Cheri,” and also includes shorter examinations, such as “Maybe It Happened” in which a day with manifold possibilities for event is described. The reader, or at least this reader, finds herself examining all the events that seemingly didn’t happen but which might have. The essay sets motivation against actual occurrence or event, which in this essay, there are none. We always ask, Why? Perhaps the question is Why not? Within a canvas teeming with possibilities, with motivations, why does usually so little actually happen? This small essay profoundly questions one of journalism’s most recent—and highly questionable dictums—Find the Story. Not all news constructs a story, there’s that, but also the world into which some event happens already has its myriad stories, most of which don’t erupt into untoward event, most of which don’t particularly shed any definitive light. So many false equations, assumptions, and somewhere in there is perhaps, on some given day, a catalyst, a detail that answers a Why, but on any other given day a detail as benign as a pie cooling on a kitchen counter.

No one writes like Jo Ann Beard, and certainly no one writes non-fiction like Jo Ann Beard. I haven’t read everything, so that seems on the face of it a fatuous claim, but who does this? Who writes an oncologist closing a terminal patient’s chart, holding his hand out to shake that terminal patient’s hand—and then starts the next paragraph with “And this, of course, is when the world turns glamorous.” What follows is a paragraph reminiscent of a Gerard Manley Hopkin’s poem, full of light and beauty and color and ardor, a paragraph that ends with “It’s all lovely beyond words, really,” a sentiment so enlivened and visualized we see through eyes just told they’re about to see no longer.

Some people hold so ideologically to the idea of time as mathematical measurement they deny the particular infinity of a mind at work on any given perception, and that is where Jo Ann Beard’s pen enters and gathers and gathers and gathers. There are twenty vital pages between a shovel coming down against an attacker’s head, the sound of this, and a resumption of this (joyously heroic) act. Reading these pages is a wonder, but one is also aware that twenty pages’ worth is just a fraction of what could be there, just a suggestion, a sliver.

In “Werner,” the transitions into his past—a real past, by the way—set him youthfully high up on a trestle bridge, goaded by friends to jump into the river below, a scene that becomes a gymnastic meet, our guy watching his teammate almost lose a hand on a vault, all this psychic backstory, all completely factual. So when Werner Hoeflich actually dives from his fourth floor window through the window of a building close by to save himself from being burned alive, not only are we not surprised, we’re like “fuck yeah, of course he can do that!”

Beard never forgets her subject, who he is, so that a few hours later in the hospital, his body cut open to muscle and bone, Werner is getting the nurse to call his catering gigs to make sure they’re covered for the day, even claiming at one point that actually, he’ll be fine to work. We understand muscle memory, have just experienced it, but we also understand that memory is its own powerful muscle. Werner survived that leap from the trestle bridge, and there’s a girlfriend now, and art he wants to make, and the man who dives through that window glass penetrating just past his knees to an apartment in another building is as much a mind as a body, layers and layers of a personal history as striated and powerful as the subject’s physical muscle.

It’s not how much a writer publishes, but how good that work is, and Festival Days is long awaited, and unremittingly brilliant.