Is Jonathon Keats an artist? I have never doubted this over my nearly twenty years of working with him on various projects, even while Keats himself has often resisted and resists such a definition, preferring the title of an experimental philosopher. Keats is represented by an art gallery (Modernism, Inc.) in San Francisco and has had exhibitions and installations in many art museums and galleries internationally. And yet, while his projects are widely covered in the press—both specialized and general-interest—art publications shy away from giving him coverage. Keats purposefully operates on the margins of the art world, seeing it as too limited for his ambitions as a public intellectual. Yet he mines the history of modern and contemporary art, borrowing its mechanisms so as to create a sense of the absurd, provoking his viewers and dislodging their expectations.

While interpreting, in what follows, twenty projects—or thought experiments—out of the many more that Keats has created over the past two decades, I attempt to show that his installations, events, research projects, publications, and texts do, in fact, as that term has come to be understood within the generic contexts and trajectories of the conceptual and of performance art movements, amount to what might rightfully be called “art.” Starting with Twenty Four Hour Cogito (2001), I focus on the objects—the material manifestations—of Keats’ thought experiments and analyze their visual rhetoric. What do such experiments yield as artifacts and how do the latter connect to the visual languages of experimental art, commercial design, and film?

Gathering the objects, images, and documentation needed to illustrate these twenty projects has required an archaeological feat of nearly a year’s duration. Keats keeps moving on, from one thought experiment to the next, without assigning to these materials the gravitas of objets d’art. Like the remnants of cultures come and gone, Keats and I excavated these objects from shelves, boxes, cupboards, and storage units, thereby producing a veritable archive with which to evidence the volume and the weight—the output—of Keats’ thought experiments. As a curator, I am struck by the latter’s aesthetic consistency, by their conceptual rigor and by how masterfully they have been executed. I am, I have to say, seduced by Keats’ objects.

But what kinds of objects are these, and what is their role in the work of the philosopher/artist? First, there are the found objects—a desk bell, an antique fountain pen, or a vintage tweed jacket—that are in turn reused in a number of projects. The latter function as theatrical props, signaling a bygone era and situating the project in history, while the subject matter itself often consists of futuristic theories and technologies, such as neuroscience or artificial intelligence. Secondly, there are the various prototypes for inventions, including schematic drawings, blueprints, models, and modified or rigged devices. Examples of prototypes include antique cameras modified to capture a century-long exposure (see Deep Time Photography); blueprints for invisible dwellings in Speculations; and adaptive technologies for endangered species in Reciprocal Biomimicry. Thirdly, there are objects that are meant to be exchanged and distributed, such as the merchandise in The Local Air & Space Administration or the cardboard-box mailing kits with slime mold in The Plasmodium Consortium. Lastly, there is printed matter—promotional posters and postcards, books and legal agreements—all meticulously designed by Keats himself and demonstrating a deep knowledge of design history. Typeface, paper, and style are chosen so as to make specific visual references, as, for example, the broadside-style graphics in the Strange Skies film poster (Cinema Botanica), the old-fashioned carbon-copy receipts in Speculations or the mid-century modern product labels in The Local Air & Space Administration.

The objects provide a curious artistic counterbalance to Keats’ philosophical texts. For every project, Keats authors a press release, which then effectively functions as the main text of the thought experiment. The press release, in turn, sets off a media campaign with accompanying interviews, reviews, and conversations in print and online. Since they form an integral part of each experiment, the press releases are attached to the individual analyses included with each of the twenty projects in this book. While the precise language of the press release spins an absurdist tale, based on an au courant event or a scientific theory, the objects in the associated installations and performances tell a different story. For instance, in The God Project, which focuses on genetic engineering technology, in connection at high-profile research institutions (e.g., UC Berkeley, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, the Smithsonian) the audience encounters Keats as he handwrites names on membership cards with an antique fountain pen in front of an experimental setup with bell jars resembling an amateur 19th-century biology lab. In The

Epigenetic Cloning Agency, which takes up the latest cloning technology, viewers see Keats behind a desk with vintage pill bottles, a desk bell, and a sign reading “Jonathon Keats, Dispensing Epigeneticist,” suggesting someone minding a counter at a frontier-town apothecary. The quaint execution of thought experiments renders them timeless, exposing the folly of our beliefs in the latest theories and the shiniest technologies.

The precision with which Keats crafts texts, objects, and props helps to configure each project as a separate microcosm. Each thought experiment is, so to speak, conducted in a controlled environment. The audience is invited to step into Keats’ universe, to share the stage, and to participate along with him. From the press release to the promotional graphics to the performance props, the contracts, the membership cards, the receipts, and the merchandise, each project comes to seem sui generis and thereby all the more absurdly persuasive. This is a conscious strategy on Keats’ part, making it difficult to pull out, step back, and discuss the work in terms other than those he sets for us himself. The staged media coverage and conversations generated within each project often merely recirculate a language that is in fact Keats’, thereby amplifying the artist’s own ideas. The resulting airtight resistance of his projects to interpretation perhaps helps to explain the relative lack of art critical attention paid to Keats’ work. What art critic will know what to do with an artist who writes his own masterful press releases, orchestrates effective media campaigns, designs promotional materials and installations, performs, lectures, and authors interpretative texts?

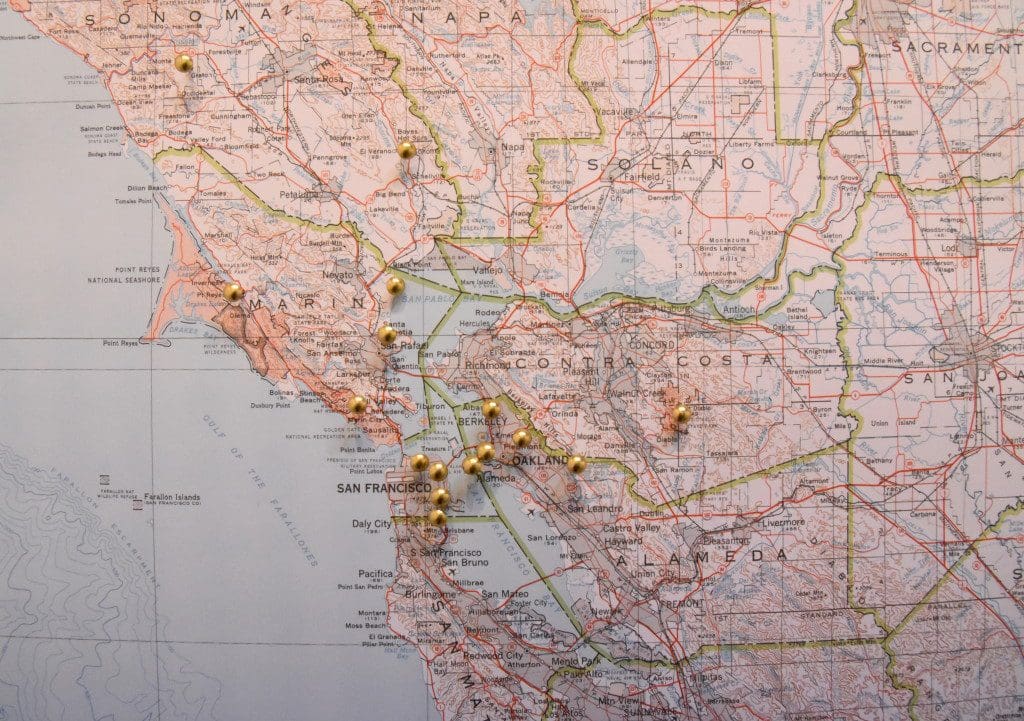

In addition to drawing attention to Keats’ aesthetic, I have here also attempted to wrestle, analytically, with the artist’s “master-of-the-universe” modus operandi by using a three-pronged strategy. First, I summarize each of the twenty thought experiments factually, unearthing what actually occurred, where, and when. This includes exhibition and performance history, institutional collaborations, publications, etc. Secondly, whenever possible, I link the projects to events from Keats’ personal history or to the world events that triggered them. For instance, in Quantum Entanglements we get a glimpse of Keats’ marriage; in Speculations, we get a sense of the concerns elicited by the 2007–2008 financial crisis and runaway real-estate speculation in San Francisco, where Keats lives; while the context for Pangaea Optima is the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement after Donald Trump was elected president.

And then, finally, I am so bold as to break the seal of Keats’ controlled environment by asserting his place in a lineage of modern and contemporary artists. Aspects of projects such as Twenty Four Hour Cogito and Bureau of Standards are here shown to pay homage to Marcel Duchamp, Marcel Broodthaers, and Sol LeWitt. Many others, including Intergalactic Omniphonics, are inspired by the Fluxus artists. In a number of cases, rather than making connections to historical artists or movements, I point out how Keats enters into dialogue with contemporaneous works such as Genesis by Eduardo Kac in Keats’ The God Project and Sarah Bergmann’s Pollinator Pathway in his The Honeybee Ballet. The aim of the art historical exegesis is not to point out Keats’ influences, but rather to show that in their material, visual execution, his thought experiments are not totally sui generis after all, and deploy many tropes developed by experimental artists over the past century.

If Keats is an artist, then what kind of an artist is he? He vehemently resists being labeled an installation or a performance artist. His own terminology for what he displays or stages includes such words as “launch,” “event,” and “research,” terminology common to corporations and governmental institutions, in line with his role-playing as a CEO, a producer, or a chief scientist. In my analysis, I choose to use standard art historical terminology—e.g., performances, exhibitions, screenings, and publications—as a way to avoid being trapped in Keats’ own language. I admit that this is arbitrary and driven by my curatorial biases, but I need the museological apparatus to step outside of Keats’ gambit and train an objective lens on his playfulness.

If Keats’ work is performance, what kind is it? Keats wears many hats and adopts multiple roles in his projects. A publicist, a scientist, a composer, an inventor, a real-estate developer—he is capable of stepping in and out of character, at times being an actor in a one-person play, at other times, a short-staffed administrator of a nonprofit arts organization. We can think of each opening event, each project launch, each evening in which Keats encounters a gallery audience, as an individual performance. Alternatively, we can think of each project or thought experiment, however long it lasts and across whatever terrain it occupies, as a performance. Additionally, we can consider the totality of Keats’ thought experiments over the past twenty years as composing a single performance in which he plays the part of a tweed-clad experimental philosopher. I have tried over the years to peek behind the stage set to see if there is a different person inside the costume, and have yet to find one. But perhaps what we have here is not a performance at all, but rather the extension of a complex and multifaceted personality; not a persona, but rather a genuine manifestation of character.

In the end, however, I follow Keats’ lead and question the need for any such certainty. Instead of pinning him down on the art historical classification chart, I’ll admit that he remains, to me, an enigma as an artist. He has developed a genre that has precedents and antecedents, but with which there may be nothing truly comparable. Keats usurps the art world in order to reach beyond it and to develop a platform broad enough that, once situated upon it, we can then ask fundamental questions about how we live and where we are heading. Jonathon Keats is an artist-as-public-intellectual, a rare species. I will enjoy wrestling and wrangling with many more of his future thought experiments and marveling at the elegance of the objects he sets before us.

Alla Efimova is the former director and chief curator of The Magnes at the University of California, Berkeley, one of the largest museum collections of Jewish art and history. She also co-published two of Keats’s artist books together with Modernism, Inc.: Yod the Inhuman and Zayin the Profane. Efimova is the author of several books and catalogs and has taught at the University of California, Berkeley, Santa Cruz, and Irvine as well as the San Francisco Art Institute.