“He traveled a lot and he traveled light. He always carried a raggedy Pan Am bag about the size of a large toaster, in which he packed a change of underwear and an old navy tie in the unwanted event that a tie might be required somewhere, and he didn’t want to embarrass his host. And he always carried small notebooks, which he filled with images, poems, political observations, character sketches.”

These are Nancy J. Peters’s words portraying her business partner and lifelong friend, Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Her tribute to San Francisco’s first Poet Laureate was paid on the occasion of Ferlinghetti’s 100th birthday, and celebrated the official proclamation from the city of San Francisco (March 24: Ferlinghetti Day) in a packed City Lights Bookstore, with crowds of every generation lining up outside on Columbus Avenue, and all over North Beach.

Peters depicts Ferlinghetti as a tireless globetrotter who “just happened to be present at so many watershed events of his century while they were happening.” The Ferlinghetti Century, indeed! The list of historic events he witnessed is pretty long, but just to mention a couple: the Normandy invasion, and Nagasaki a few weeks after the bomb leveled the city. (A recent exhibition at the Harvey Milk Photo Center showcased some of the photographs Ferlinghetti took as a young navy officer in Cherbourg.) Peters continued listing milestones of Ferlinghetti-being-present: “In the wake of the Cuban revolution he was in Havana. During Nicaragua’s struggle for autonomy he was in Managua. During the May ’68 insurgency in France, he was in the streets of Paris while students were scrawling radical poetry on the walls.” And his travels continued for years, all across the United States, Europe, Russia, North Africa, and Australia. Peters reminds us that some of the greatest souvenirs “the People’s Poet” brought back to San Francisco from around the world were “dissident poets like Yevtushenko and Voznesensky to perform for huge audiences, and good poetry to translate and publish. His choices and his art opened public space for new voices, censored voices, foreign voices.”

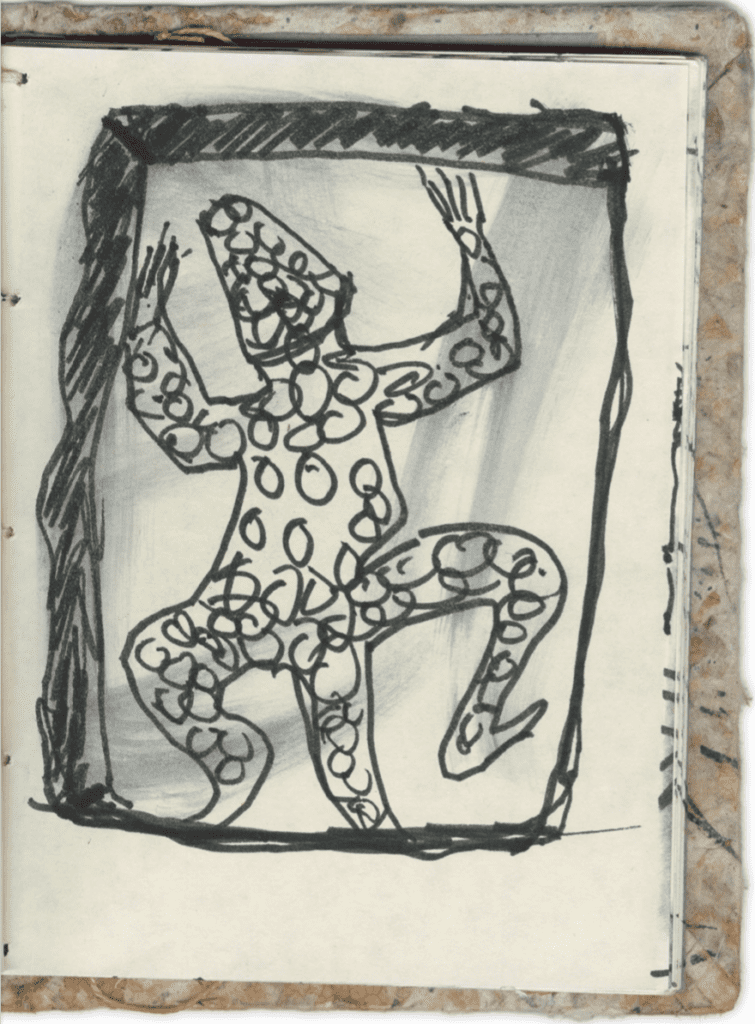

And from every voyage, Ferlinghetti brought back notebooks, where new ideas unfolded with drafts of stories and, most of all, lots of drawings, masterfully sketched, often in journals made of artisanal vegetable fibers from Oaxaca, paper on which ink hypnotically flows and expands while brushstrokes playfully scrape shades into shapes. The best way to visualize, in Ferlinghetti’s own words, “a reporter from Outer Space [covering] the strange doings of these ‘humans’ down here, sent by a Managing Editor with no tolerance for bullshit”—is to read his book Writing Across the Landscapes 1960–2010 Travel Journals (New Directions, 2015). Thanks to this publication, edited by Giada Diano and Matthew Gleason, we can understand Ferlinghetti’s work “in the tradition of D. H. Lawrence’s travels in Italy or Goethe’s Italian journeys”; the well-known “clericus vagans” who tries to seize the day with the same urgency of a bullfighter: notes, ideas, puns, quotes, characters, faces, landscapes, masks, and animals interwoven from page to page. Going through these travel journals, we can witness, almost like walking in real time with him across more than five decades in his “walkabout in the world,” how he was writing and sketching with his distinct lightness, style, curiosity, and excellent sense of humor. “I was just a dog walking the streets, observing and noting everything happening around him.” That’s the quintessential self-portrait of the young artist Ferlinghetti has described to me many times, but it is also the mark of his creative process.

Latin America, and specifically Mexico, has been a ritornello in Ferlinghetti’s lifetime score, its rhythms provided by his many travels, plethora of acquaintances, and the most diverse kind of friends, a never-ending volcanic activity of insurgent art and outstanding poetry. From the first journal (1960) to the most recent (2010), the voice and the sign of Latin America plays the prologue and the epilogue.

Beyond so many words spread like seeds—spoken ones, written ones, read, reread, interpreted, sung and performed, again and again—the lyrical heart of Ferlinghetti’s poetry actually lies in the bosom of his drawings and sketches. Here’s the origin of the voice’s timbre, and of the little boy eternal in every human being, particularly so in the poet. These notebooks are Ferlinghetti’s artistic magma, what Antonin Artaud—who wrote Mexico and Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumaras—called “la parole avant la parole” (the word before the word). If, according to Heraclitus’s aphorism, the God whose Oracle is in Delphi neither indicates clearly nor conceals but gives a sign, we can assume it’s not just nature that loves to hide, but sometimes art as well.

Latin America for Lawrence is not just a geographic destination, but also an aesthetic category of contrast: dictatorships and revolutions; ancient rituals and masks, and modern, Western ones; joy and despair at their peak. The notebook excerpted here is dedicated to the Mayan gods—an homage to the pre-Columbian civilization and its mysterious signs. This physically small notebook is dated 2004, coinciding with an exhibition (“Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya”) organized at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, where Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Rigoberta Menchú gave a special presentation.

Ferlinghetti’s sketches are charming because of their simple touch, incisive gestures, and unflagging humor. No matter if it is a figure or a mask, a statue or an animal, each is a monument contained in a few lines. It would be a dream to one day see a whole catalog dedicated to Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s notebooks. No words, and no explanations, just the golden silence of the poet’s joyful signs, following in the Sicilian saying, the best word is the one you never say.

Mauro Aprile Zanetti is a San Francisco author and served as personal assistant to Lawrence Ferlinghetti, with a background in independent filmmaking. The notebook excerpted in the following pages is reproduced at its original dimension of 4 ½ × 6 inches. For more information about Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s art, visit ferlinghettiart.com.