2021 is well under way as we nearly bid ‘farewell’ to February. Of course, we wouldn’t let the month pass without a small treasure trove of media for our readers to potentially enjoy. With that in mind, we present our Staff Recommends, February ’21 edition:

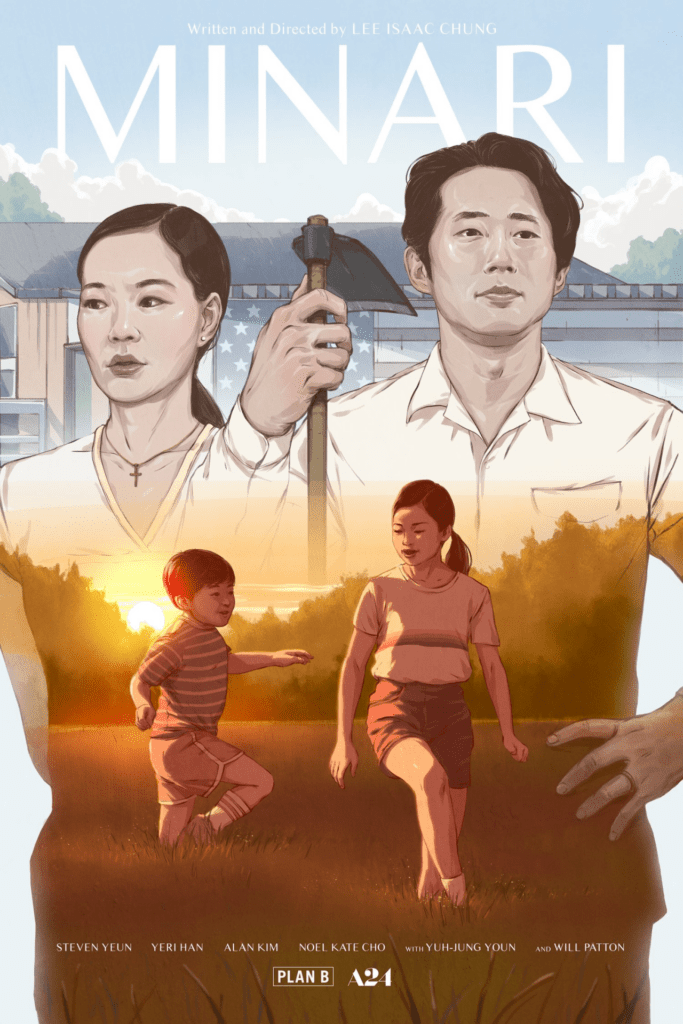

Kyubin Kim, Intern: Since the film’s premiere at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, it is not an exaggeration for me to say that I’d been waiting all year for the public release of Minari. I religiously followed production studio A24’s social media updates, read interviews with director Lee Isaac Chung, and even DM’ed actor Steven Yeun on Instagram to tell him how excited I was. And after failed attempts to win raffles for an advanced film screening, on February 12, 2021, I finally logged into my A24 account for a virtual screening of Minari.

Minari follows a Korean family who moves from California to Arkansas to fulfill the father’s homesteading dream to be the first Korean farm to serve the South. Jacob hauls his reluctant family of four, including his wife Monica, precocious daughter Anne, and endearing but mischievous son David, to the barren land with the “best dirt of America.” Shortly after, the family is joined by grandmother Soonja, whose wild-haired, out-of-place Koreanness clashes with the family. Minari is based on director Lee Isaac Chung’s childhood in Arkansas, and the film’s autobiographical heart is infused through the joyous slice-of-life style of the cinematography. Alan Kim, who plays David, marches across the farm in cowboy boots and knee high socks with a spunky cuteness that the audience can’t help but root for. There are hilarious jabs at cross-bearing Christians and toilet humour that never fails to disappoint, but also tender moments of what it means to grow roots in a new country.

Regardless of the awards that Minari has been and is anticipated to rack up, the film was a historic moment for Korean Americans, including myself. I grew up in a Korean-speaking household and it was the first American film that my parents could watch without complaining about subtitles (the dialogue is predominantly Korean). At scenes of Jacob and Monica sexing chickens at a factory, my mom pointed out excitedly, “Look! That’s what the early Korean immigrants before us had to do.” Watching Jacob’s stubbornness as the patriarch, we stared pointedly at my dad who sat, arms-crossed, pretending not to notice. Quite frankly, it was the first film where my family could identify with American cinema.

But even more, Minari, as an intimate lens into one autobiographical family, lends credence to the statement that specificity is the path to the universal. Minari tastes like hope when it feels like the path to progress and inclusivity in Hollywood is so difficult to accomplish. Minari shows us why we as Americans believe, almost to a fault, in a promise that is not always realized in our lifetime. When the film ends with the folksy murmur of Emile Mosseri’s score and the credits roll on a pitch black screen, I see my family of four reflected across the television. In this quiet moment, I find solace in Jacob’s words: “Even if I fail, I have to finish what I started.”

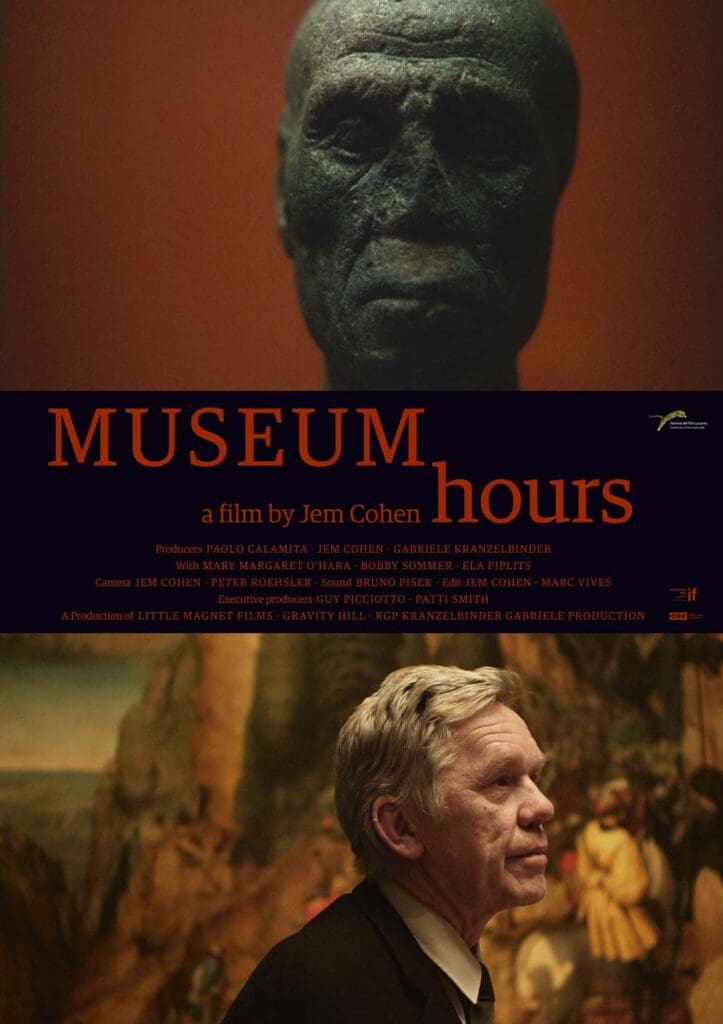

Owen Torrey, Intern: Midway through Museum Hours, the 2012 feature by filmmaker Jem Cohen, the scant plot that has structured the film thus far pauses altogether. For the ten minutes that follow, we join a tour group at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, passing before a series of canvases in the Brueghel Room. “What is the center of this painting?” our tour guide asks, facing The Conversion of Paul. “I might argue that the center is the fine tree, sheltering this little boy in the helmet. Look at him.” And we do: the screen filling up with a flash of brushstrokes, before the tour heads to another room, and the film continues on its way.

The rewards of Museum Hours are simple and quiet, meditative and many. The film’s center, to the extent that there is one, is the relationship between Johann (Bobby Sommer), a museum guard, and Anne (Mary Margaret O’Hara), a Canadian tourist. The two meet one winter afternoon at the Kunsthistorisches. As they talk about art—and talk about themselves by talking about art—a warm friendship is sketched out. As narrative scaffolding goes, it’s pretty thin, and mostly just gives Cohen’s camera an excuse to drift through the gallery by their side, picking up everything as it does: fine details of canvas color, dulled echoes of conversation, slow groans of wooden floors underfoot.

Yet for all its interior detail, Museum Hours gazes outwards, too, finding echoes between those antiquated paintings and the humming life beyond the museum’s doors. One of the film’s preferred techniques is to focus on a small patch of a canvas (a crow, for instance, in Brueghel’s Hunters in the Snow) and then cut to that detail’s visual counterpart somewhere in Vienna (a real bird, flinching in a tangle of branches). Through these art-life doppelgangers, Cohen asks us to approach what is closest to us with the same reverence we might grant a work by an Old Master. These days, I can’t go to Vienna, or the Kunsthistorisches—or most museums, for that matter. But I can glance out, from my desk, towards my neighbor’s leafless elm. I can look—really look—at the sparrows that gather there each day, looping around themselves, scattering away as I write this now. This, Museum Hours suggests, is pleasure enough.

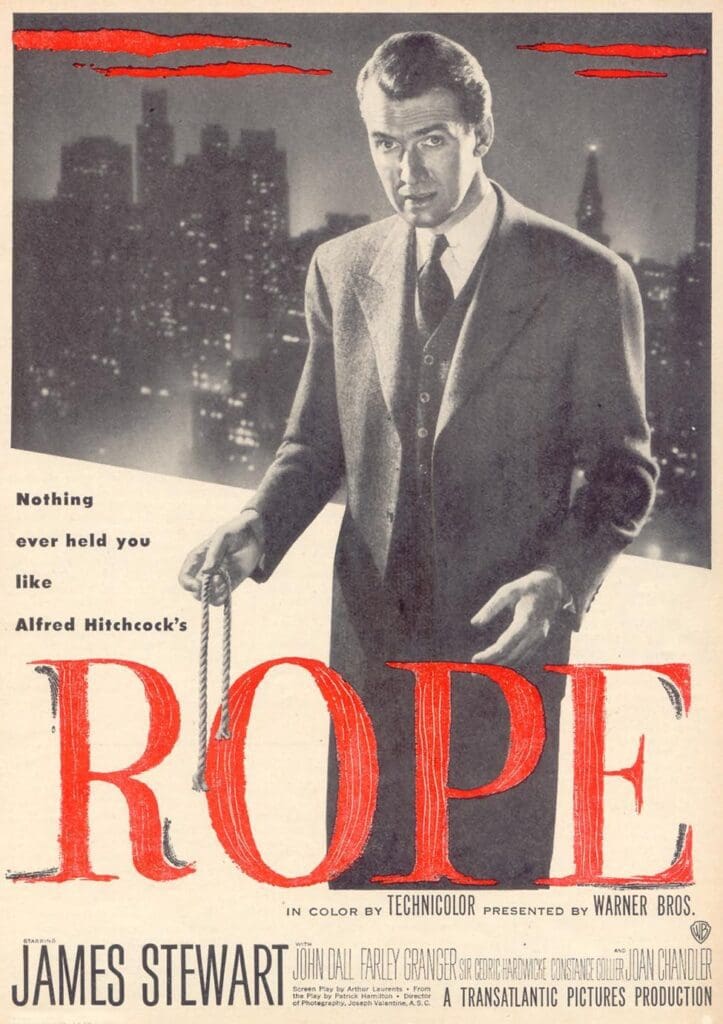

Lily Nilipour, Intern: My family’s latest quarantine activity has been to slowly work through Alfred Hitchcock’s entire oeuvre. We have no illusions about actually being able to achieve this—the prominent director made over 50 films during the course of his career—but we’ve made progress nevertheless. Rope (1948), the tenth movie in our endeavor, offers a unique and intellectual take on the classic murder-mystery that Hitchcock was so instrumental in developing.

A psychological crime thriller, Rope begins with the death of a young Harvard student named David who is strangled by two of his longtime classmates and friends—Brandon and Phillip—simply for the sake of proving their “intellectual superiority” by their ability to commit the perfect murder. Then, with a warped sense of humor, they hide the body in a chest in the room where they are about to host a small party with David’s parents, David’s girlfriend, another schoolmate, and their old philosophy teacher Rupert. The rest of the movie ensues in almost claustrophobic suspense, as we wait to see whether the party attendees will piece together the reason David is missing from their entourage.

Besides its engaging plot, the technically experimental aspects of Rope make it an even more compelling quarantine watch. The entire movie takes place in the space of a single room, heightening the tension of the mystery. It is also shot to give the illusion of one continuous take, and all necessary cuts are cleverly disguised by the camera zooming in or out at opportune moments. I found the confined, continuous experience of Rope an unexpected but interesting parallel to the life we are living now and enjoyed the movie all the more for it—though I am perfectly content with the parallels only going that far, and without the unbeknownst presence of a corpse accompanying me in my own living room.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: With the arrival of any new year, I’m always curious to see what will be the first album to truly capture my attention. As an obsessive music listener, I know the releases of these early months tend to bode little for the year to come; and certainly there have already been a host of pretty good records released in the first two months of 2021. But as a Bay Area resident, it does my heart a bit of good to say the best album of the year so far is by Oakland’s very own Fawning. A duo consisting of Cheyenne Avant (of fellow local band Night School) and Devin Nunes (no relation to the politician—he’s the drummer for shoegaze act Whirr), the two-piece put out their debut EP Too Late in 2019, citing the Cocteau Twins, Cranes, and Julee Cruise among their influences. If those names don’t clue you in to what kind of sound Fawning creates, I’ll just say their music is released by a subsidiary of Graveface Records called NeverNotGoth.

Even so, it must be said their debut LP Illusions of Control, out this month, represents a dramatic expansion of the band’s sound and abilities. This is the kind of record that will make you feel like the Eighties never ended—eight dense and dreamy tracks of ambient synthesizers, cavernous-sounding drum machines, and atmospheric guitar lines, with Avant’s ethereal vocals floating blissfully above. Listen too for the subtle touches that deliver pleasing associations of all those classic albums from The Cure like The Head on the Door and Disintegration, whether it’s the intimation of cathedral bells on “Wait” or the surprise saxophone solo that closes out “Nothing Matters.”

True, with a new administration in the White House and vaccinations ramping up across the country, you might say things are looking up—but with so many of us confined these last 12 months, it’s certainly been a year for bedroom music. In that regard, Illusions of Control must be one of the best examples of its kind; much more than a mere homage to the new wavers who have come before, it’s a lovingly-crafted contribution to the dream pop genre, one that conjures its own cobwebbed grandeur.