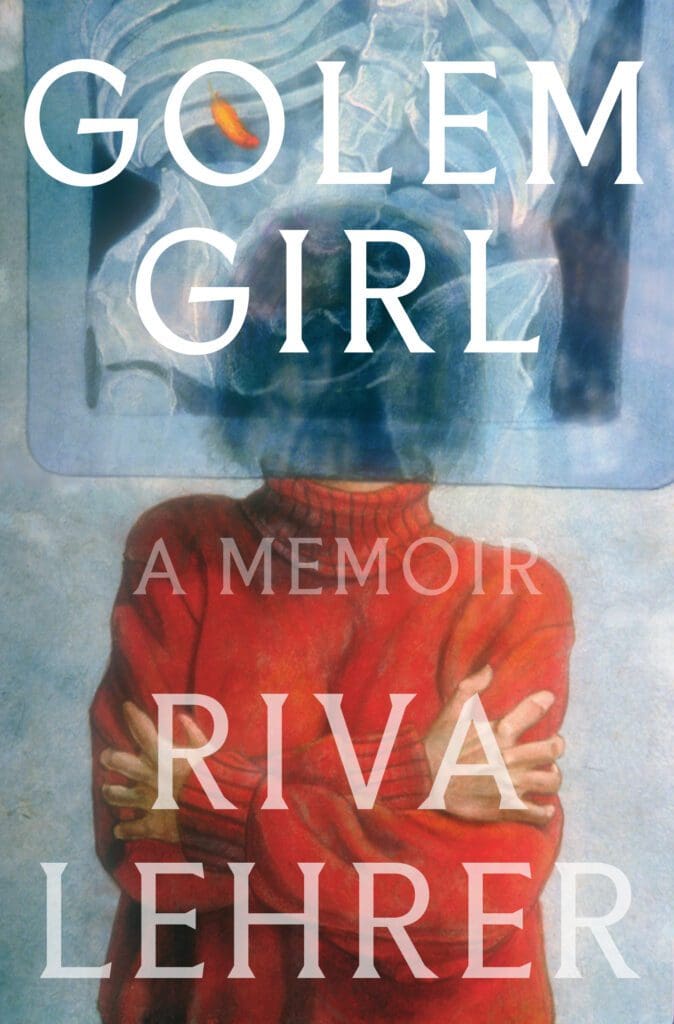

Artist, activist, writer, and professor Riva Lehrer’s debut memoir, Golem Girl (448 pages; One World), is a book defined by its author’s witty and confiding voice and the numerous paintings and photographs populating its pages. It is at once a work of serious literature and an artist’s book: a beautifully produced physical object. And it was recently named as one of the finalists for the National Book Critics Circle Awards in Autobiography.

Lehrer, born with spina bifida in Cincinnati in 1958, spent the first two years of her life in the hospital and would have been forced to stay longer if her mother, a medical researcher, hadn’t during those two fraught years figured out how to convince her daughter’s doctors that she would receive proper care at home. Up until the mid to late 1950s, most babies born with spina bifida didn’t receive the surgeries needed to save their lives, but Lehrer’s mother’s knowledge of recent medical advances ensured her first-born child received timely surgical procedures.

These postnatal surgeries were the first of many Lehrer received throughout her infancy, childhood, and adolescence. With precision and lively humor, the author describes the harrowing procedures she was subjected to (including a hysterectomy “sold” to her as a cure for painful periods), and the different doctors treating her and her mother—who, after slipping and falling while snow-shoveling, was the victim of a badly botched back surgery that ruined her health and quality of life. She died the summer before Lehrer began her senior year of high school.

The opening line of Chapter 26, “Mom and I always dressed up for a doctor’s visit, it being our version of church,” is a good example of the humor that is this memoir’s default mode, which has as much action, suspense, and villainy as an Ian Fleming novel.

To say that Golem Girl is sui generis is only a small part of this book’s great appeal. Most (all?) artists, in one way or another, strive to be seen and acknowledged, and for an artist living with a disability, it is often the disability alone that is seen by the ableist gaze. With Golem Girl, Riva Lehrer has created an extraordinary—a glowing—work of art. She and this book are so bright, so clearly visible, they’re dazzling.

This interview was conducted via email.

ZYZZYVA: Did you envision Golem Girl first as an art book, with a few personal narrative sections as companions to the artwork? Or did you always know it would include as much writing (and art) as it does?

Riva Lehrer: The book actually started simply, and not even as a book: I had wanted to leave a document for my family about my work, as they were going to be my art executors. It was only meant to be text (not a catalog in any way). I wanted them to have something to send out, refer to, whatever they needed after I was gone. But in explaining my work, I’ve always had to include a certain amount of personal history. So I was used to telling stories when I lecture in public, in classes, conferences, guest speaker gigs, etc.

As I wrote, I realized that there were gaps in some of my early history, questions that began to puzzle me. I began to research my own past, and that’s when everything changed. I had not known that Mom was a medical researcher. I’d thought she was Dr. Warkany’s secretary (Editor’s Note: A medical researcher for whom Lehrer’s mother worked for a time). I don’t know why she never told me—or maybe she did, but I misunderstood. When my Uncle Lester told me the truth, what I knew about myself turned upside down.

And then my family told me a lot more truth…

I figured that the “book” would never be more than a box of papers under my bed. But then, in 2017, a series of remarkable events happened that led to the acquisition of my draft by One World, an imprint of Penguin Random House. All of a sudden, that pile was destined to be a book.

As the manuscript grew, it became clear that my work was totally entangled with my history. The images we included (except for the photos) are NOT meant as illustrations. (I hate when reviews call them that.) I constructed a conversation between my visual and personal narratives.

Z: Are there books or other works of art or literature that you had frequently in mind as you wrote Golem Girl and drew and painted?

RL: Not so much. There aren’t many memoirs by visual artists; they tend to be monographs focused narrowly on their studio work. I did think about Sally Mann (e.g. Hold Still), but my three most germane models were Lucy Grealy’s Autobiography of a Face, Terry Galloway’s Mean Little Deaf Queer, and The Memory Palace by Mira Bartok.

Z: Your narrative voice is immediately engaging, and your writing style is both precise and lyrical—your expertise made me think you have long been a writer as well as an artist. This is your first published book, but are there other manuscripts that came before this one?

RL: Nope. A few published essays based on my lectures, on beauty, gender, the history of portraiture, and two op-eds for the New York Times. That’s it.

I do have a lot of experience in public speaking—trying to engage and hold an audience is never easy, especially if the material is a little dry.

Most of my work is about representation. How stigma around disability, queerness, race, gender have made countless human beings grow up ashamed of the very home of the self. About how we see each other, aspects of gender and desire. Why the Disabled body is all too often considered the very paradigm of ugliness; the effect of self-loathing based in homophobia and ableism; how images in the media endlessly destabilize our ability to remain peacefully in our own bodies, against the push to always be other—younger, whiter, thinner, unmarked…

So I’ve written dozens of public lectures keyed to images (my own and others’) that taught me how to weave together the visual and the verbal.

Z: I love the short chapters punctuated by drawings, photographs, and paintings. Did you have long chapters at one time but decided eventually to break them up?

RL: No—I think, I guess, sort of poetically. Tried to make each chapter its own aesthetic experience. Long chapters drained away the—aura?—I worked to build through metaphor, symbol, rhythm.

Z: As you note above, much of your work is about representation. When you were studying art at the University of Cincinnati, you began working with other artists who rejected, as Golem Girl’s flyleaf states, “tropes that define disabled people as pathetic, frightening, or worthless.”

In spite of what the pandemic has made clear about the U.S. healthcare industry’s withering regard for the elderly and people living with disabilities (a topic your New York Times op-ed of March 21, 2020 addresses—also included in this book), do you think most medical professionals no longer routinely tell their patients with disabilities, as you were told in the 1960s and 1970s, that they have no hope for a “normal” life, i.e., marriage, childrearing, a fulfilling job?

RL: To some extent. I think, in general, things are more enlightened—but. It really depends on the impairment and the doctor. I have so many female friends who were told not to get pregnant, either because their child would have (oh horrors!) a disability, or out of fear that pregnancy would damage the mother’s body, or that they’d never be able to carry the child to term. Or that, if they did, they were not likely to be competent mothers. Many are virtually forced to get genetic counseling, whether they want it or not. Mind you, this is NOW, not ten or twenty years ago.

Some of these women have written their own texts about this persistent prejudice. I think of Rebecca Cokley, nationally known activist and director of the Disability Justice Initiative at American Progress, or Sunaura Taylor, renowned theorist, artist, writer, and professor at UC Berkeley, two highly accomplished women who both tell of bad reactions by the medical profession to their plans for motherhood.

I have heard much more positive stories. (See the documentary Far From The Tree for a look at the complexities of Disabled parenthood.) But if adroit women are treated this way, I can scarcely imagine what less privileged crips—of whatever genders—go through as they seek OBY-GYNY support.

And whenever I go into Northwestern Memorial Hospital, there’s always a moment (or many moments) when medical staff are astonished that I have a job, much less that I teach at their own medical school.

Z: One fact I was reminded of while reading Golem Girl is that the United States was the birthplace of eugenics. Tangentially, the ableist gaze deeply informs Western culture, and I’m wondering (forgive me for what is probably a maddening question) if there were one permanent change you could effect in representations of people living with disabilities, what would it be?

RL: Huh. I would hope for demystification about who we are and how we live. Half the time outsiders believe our lives are tragic, when they’re just difficult; on the other hand, a wish that they could see the power and joys inherent in disability, clearly, without sentimentality.

Even more than that, I wish that all disabled people could see themselves as Disabled, capital D. Twenty to twenty-five percent of all Americans have a disability. We’re the largest “minority” in the country, perhaps the world. Right now, people with disabilities seem to be totally left out of governmental plans around COVID mitigation. The phrase “underlying conditions” is not helpful; it makes us seem as if we’re hiding something, or that our impairments are secondary issues.

And stop thinking that people without life-threatening impairments aren’t in danger. Just consider that a person who uses a wheelchair might not be at direct medical risk, but their roster of PAs [personal assistants] come and go, each posing a risk to that person’s “bubble.” Many of the current woes we face in this pandemic could be dealt with if we rose as a massive political force, a single nation, whether our impairments are cognitive, psychiatric, orthopedic, neurological, developmental, morphological, sensory, or as yet unnamed.

Z: I loved the portrait gallery, as I came to think of it, near the end of Golem Girl—did you know early on that you wanted to include it? (I also think of it as an artist’s catalog, as if the accompanying text were written for a gallery show, which I’m guessing is where the format might come from.)

RL: As I mentioned, the book began life as a resource for my art executors. But the portrait stories were originally called “the interstitials,” and were formatted as chapter breaks, to be inserted wherever the story took a major turn. Alas, I had to acknowledge that that approach was too disruptive to the narrative, which is when I decided on the “book within a book” structure.

Z: I was struck by a line in the passage Lauren Berlant wrote to accompany her portrait by you. She called Golem Girl an autobiography rather than a memoir. Do you think of it as more of an autobiography than a memoir?

RL: I’ve been told that the book is more in that vein—but I have to confess, I had so little training as a writer that it didn’t dawn on me that there was a difference until I was nearly at the end. I am a feral writer. Iowa need have no fear of me.

Z: What are you working on now, if you don’t mind sharing a few details?

RL: Auuuggh! I’m taking a shot at fiction. Somebody stop me, this is batshit delusion time.

Thing is, there were themes that arose in Golem Girl that felt so unfinished. I wanted to try to take them on in a different fashion. (Plus, I found that I really missed writing, rather like missing dropping a hammer on my toe). The book, tentatively entitled Animate, is a story about a young woman’s inability to deal with the fact of death, an arc that takes us from a kid’s clothing company to medical school to the cadaver lab to puppet theater.

Pray for me, that’s all I can say.

Christine Sneed is the author of the novels Paris, He Said and Little Known Facts, and the story collections Portraits of a Few of the People I’ve Made Cry and The Virginity of Famous Men. Her work has been included in The Best American Short Stories, O. Henry Prize Stories, The Southern Review, Ploughshares, and New York Times. She’s been a finalist for the L.A. Times Book Prize, and has received the Grace Paley Prize, Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year Award, Society of Midland Authors Award, and others. She lives in Pasadena, CA, and is the faculty director of Northwestern University School of Professional Studies’ graduate creative writing program.