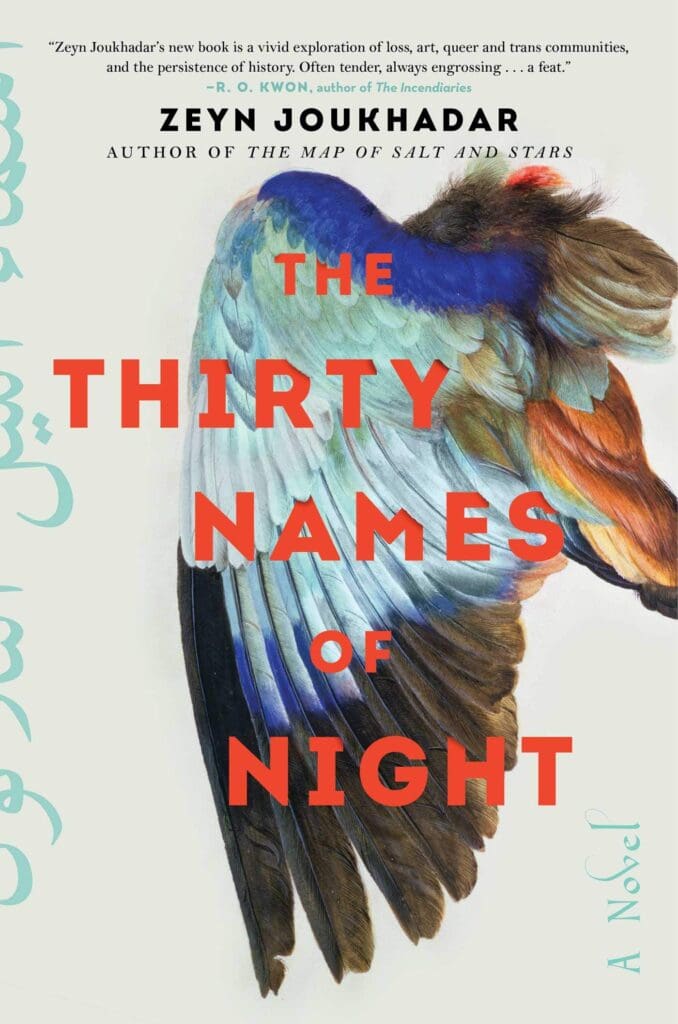

In the heart of the once vibrant Manhattan neighborhood of Little Syria, towering murals of birds cover building walls. They are the artwork of a closeted Syrian American transgender boy, who finds that it is the only way he can paint since the death of his ornithologist mother. After one night of painting, the boy stumbles into an abandoned community center where he finds a leather-bound notebook hidden in the hollow cavity of a wall. It is a journal written by Laila Z, a famous Syrian American artist who mysteriously vanished over sixty years ago. Engrossed in Laila’s story, the boy sets out on a journey to piece together her history and recover a painting of hers that will confirm the existence of a bird so rare it was deemed fictitious by those who had never seen it. Alternating between the points of view of Laila and the boy, Zeyn Joukhadar’s stunning novel The Thirty Names of Night (304 pages; Atria) weaves together an intricate story of love and loss, community and culture.

Situating the story in a version of New York where mysterious flocks of birds flit in and out of the narrative, Joukhadar’s poetic writing presents a world where the boy finds traces of his mother in everything, whether she appears as an apparition or just a faint whiff of thyme. He clings to her memory as he struggles to come to terms with his identity—and Joukhadar gives us a vivid portrait of what the loss of a loved one can leave behind.

Still grieving the death of his mother, the boy must also contend with the constant “agonizing feeling that this body does not belong to [him],” and Laila’s journal plays a large role in his process of self-acceptance. More than sixty years before his birth, Laila left Syria and came to “Amrika” with her family. But some six thousand miles away from home, what she missed most about Syria was B, the girl she loved. As the boy reads more of her journal and pieces together the fragments of her life, he uncovers the rich history of queerness in his community of Little Syria, learning that Laila, too, struggled with feeling both part of and separate from the family and friends with whom she’d grown up. The two of them encounter microaggressions and outright prejudice, but between the horrors and moments of pain, they also find friendship, love, and a network of support in those that learn to accept them. As the boy navigates the many complexities of intersectionality, he comes face to face with sexism, colorism, homophobia, and a plethora of other barriers. But this is a story that is ultimately about growth and the bonds that we form. Slowly, the boy begins to embrace his identity, understanding that his truth “isn’t inscribed in [his] body. It lives somewhere deeper, somewhere steadier, somewhere the body becomes irrelevant.”

Standing at the crossroads of art, history, queerness, and community, The Thirty Names of Night presents two engrossing narratives whose convergence is astounding and heartbreaking in turn. Joukhadar writes with intricacy and care, and the dual narratives parallel each other in beautiful and unexpected ways in this culturally and linguistically rich novel.