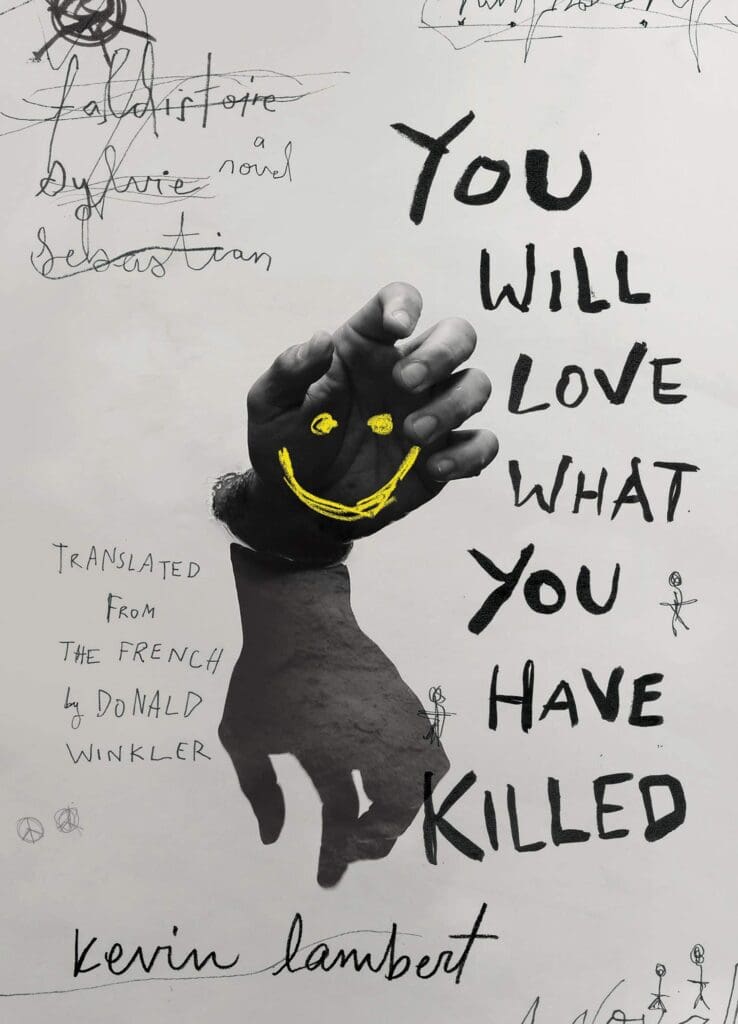

While involved in the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley during the Sixties, activist Jack Weinberg became famous for coining the phrase, “Don’t trust anyone over 30”; few novels personify his quote as sharply as You Will Love What You Have Killed (185 pages; Biblioasis International; translated by Donald Winkler), the first novel by Canadian Millennial author Kevin Lambert. The story is set in Chicoutimi, a small French-speaking town in Quebec where children more often than not end up dead at the hands of their elders. On the surface, Chicoutimi is a town that appears like any other—with its glad-handing politicians, eccentric locals, and seemingly benevolent grandparents—but in reality holds a bevy of dark secrets. This fact becomes apparent for the reader as soon as the local children begin to die, one after the other and in often unspeakably gruesome ways, whether it be a freak snow plow accident or a stabbing by a deranged family member armed “with a long knife right out of a horror film.” Is it any wonder that our narrator—a young boy named Faldistoire—vows, “…it is I who will destroy you, Chicoutimi…You are the abscess festering in the void, the tumour gnawing away at nothingness, Chicoutimi, and when deliverance will come, all will cheer your disappearance.”

But Chicoutimi will not go quietly. Since the town harbors enough evil to resemble Stephen King’s fictional locale of Castle Rock, Maine, it’s fitting that Chicoutimi displays certain supernatural abilities as well. “How far would my native city go to uphold its infamous saintliness?” the narrator poses. “Far enough to bring back dead children.” It’s no exaggeration: the children who die throughout the course of the novel crawl their way back out of the ground, in the cemetery where the croaking toads stand their not-so-silent watch. (The toads serve as a motif throughout the book.) These resurrected youngsters resume their previous lives like a modern-day Lazarus, behaving as though they had never died in the first place.

The years pass and we watch Faldistoire enter high school as he solidifies his plan to raze his hometown by the time he graduates; all the while, he loses friends and loved ones alike to the spell of grave misfortune that seems to plague the place. Our narrator’s voice remains disaffected and detached through it all, even as the body count grows higher. This neutrality proves something of a blessing: You Will Love What You Have Killed would likely be unbearable if the reader was asked to become emotionally invested in its story, as the characters are subjected to all manner of depravity, including animal maulings and sexual abuse, but fortunately little of it is ever dwelled upon in great detail. The tone skews closer to pitch-black comedy, with a style that at times recalls transgressive authors like Dennis Cooper. Lest one question just how a novel constructed around dead children could feel comedic, even playful at times, to wit: author Kevin Lambert shows up in the novel himself—albeit as a very unlucky snow plow driver rather than a writer.

The emphasis of the novel is appropriately placed not on graphic violence but on that feeling of rebellion that so often defines youth, perhaps ever since a leather-studded Marlon Brando quipped, “Whatta ya got?” when a local asked him what his gang was rebelling against in 1953’s The Wild One. It’s the creeping suspicion that the System is corrupt and engineered to benefit those who already control its levers; for the children who live there, Chicoutimi is just the loudest and most manifest expression of that inherent injustice. “I was taught to see the world through your eyes, Chicoutimi,” Faldistoire states. “I do not thank you for it.” The posters on Faldistoire’s wall include musicians who have come to symbolize this same spirit of teenage rebellion—Kurt Cobain, Sid Vicious—and, not unlike the songs of the Sex Pistols, this fleet novel attacks society’s institutions in a brief but potent burst of attitude. Faldistoire mentions reading books by “Jean Genet and Hannibal Lecter,” and one might see an effective blend of those disparate influences in Lambert’s writing: this is a novel alive to both the agony and desires of youth, with flashes of evocative violence, such as a man tossing his body onto a circular saw.

Lambert—the author, not the character—also effectively evokes the mood of a particular time and place. Although set in Canada, the novel captures the tenor of George W. Bush’s presidency and his War on Terror through frequent pop culture references (Pokémon, Harry Potter) and other details, such as when Faldistoire’s Arabic-speaking classmate Almanach is racially profiled. It should come as little surprise that Lambert’s novel makes for uneasy reading—the lives of its youthful characters prove brutish and short, and in this instance one wonders how much of a mercy it is that the children of Chicoutimi are brought back to life if it means they have to endure the town’s abuse again and again. But as out of control as the murderous adults may seem, Lambert proves very much in control; and while there’s little hope to be found in its pages, Faldistoire’s crusade suggests that sometimes the only way to overcome a corrupt System is to rip it up and start again.