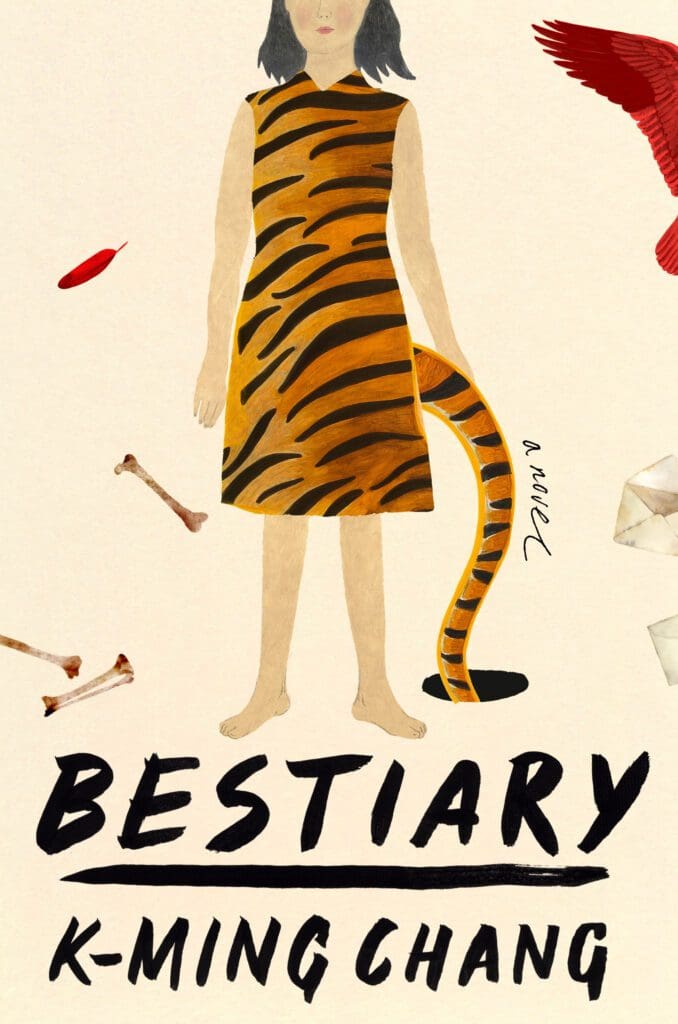

From Plath to Vuong, the poet-novelist has long been a centerpiece of literary conversation, subverting convention to craft impossibly engaging narratives. K-Ming Chang, a poet by precedent, comes prepared to contribute to that legacy. Her first novel, Bestiary (272 Pages; One World/Random House), is suffused with lyricism, a multigenerational, mythological, and magical-realist retelling of one family’s fraught history.

Bestiary’s three narrators are referred to only as Daughter, Mother, and Grandmother. Their narratives are interwoven, and converse and collapse upon each other. Though Chang’s novel is largely lyric and non-linear, its through-line is deceptively simple: Daughter learns the myth of Hu Gu Po—a tiger spirit who inhabits a woman’s body and eats the toes of children—and later wakes up with a tiger tail sprouting from her back. As Daughter battles her growing hunger and animal instinct, her family histories coalesce around her, each taking the form of a different Taiwanese myth.

At its core, Chang’s novel is about family and confronting the horrors of an inherited past. As Daughter uncovers more of her family’s traumas—why Mother is missing three toes and fears water, why Grandmother abandoned her three eldest children in Taiwan—she finds herself increasingly susceptible to her carnivorous instincts, liable to maul and hunt. “Sometimes a wound skips a generation or two,” Grandmother tells Daughter, “appearing again in the body that is most ready to wield it.”

By equating it with animal transformation, Chang portrays trauma as something corporeal, out in the open, no longer an enigmatic force inhabiting the dark of the mind. Its tangible effects in Bestiary are manifest; Chang’s prose assumes a crudeness that frequently and unabashedly presents bodily wounds, functions, and fluids as byproducts of a harrowing past. The generational pains depicted in Bestiary thus become fully embodied, impossible to ignore or explain away.

It is not only through the grotesque that Chang renders trauma as something profoundly visceral. Her prose is perhaps the most distinctive aspect of the novel, never straying far from the lyric-poetic. Chang deconstructs language, fashioning verbs from nouns, rendering the earth a landscape for each narrator’s expression. Chang and the women of Bestiary sacrifice the stability of linguistic conventions to fully convey emotional truths. In this way, the novel lights a path to the reader’s understanding of each character’s wounds. Particularly striking are Grandmother’s confessional letters, which break into unadulterated poetry:

I mourn my bones that believe they’re

home the moon a sound & your sisters the

stripes I wear. This light I lair. Now my holes are

many

While Chang’s novel is an impressive display of language, Bestiary may wear on the poetically-uninitiated reader. The prose is incredibly ornate, and each page weighs heavy with elaborate images and abstractions. As Daughter kisses her love interest Ben, a girl from Ningxia, her description of the act borders on Baroque:

We kissed, my tongue serenading her teeth. She put her palm on the back of my neck and I was sweating a dress. My hands honeymooned on her hips…[Her] ribs parted against mine, releasing her heart into my hands, a fistful of feathers. My throat a perch for her teeth.

While this steady extravagance may deter certain readers, it is also what makes Chang’s novel such a memorable debut. And for a story fundamentally about language—or the lack thereof—in the face of trauma, Bestiary’s unconventional and elaborate style provides a welcome sort of excess.