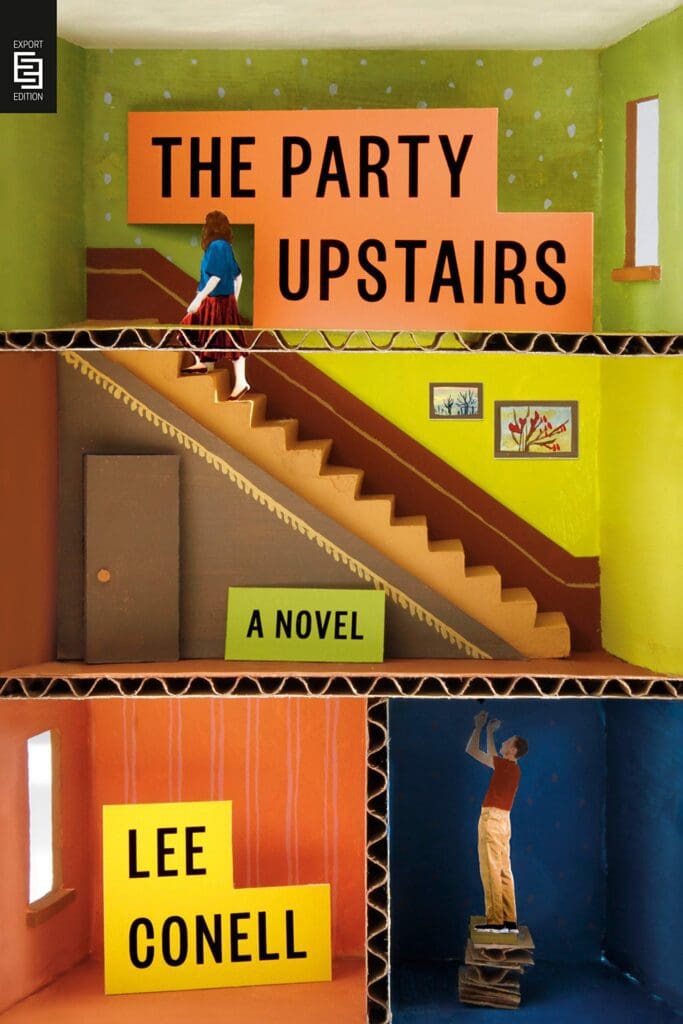

Lee Conell’s first novel, The Party Upstairs (308 pages; Penguin Random House), is a provocative testament to class division and the boundless nature of self-absorbance. Alternating between the perspectives of Ruby and her father, Martin, Conell offers us a glimpse into a microcosm of New York where tensions are high, and resentment seems inevitable. Ruby, saddled with a niche degree and few job prospects, is forced to move back to her childhood home—the basement in an Upper West Side apartment building where her father is the super. Martin, exhausted by life and desperate for a moment of peace, must continue his work in the face of familial disarray and an anxiety so deep he worries it will ultimately lead to the grave. Through the eyes of these two characters, Conell presents a vibrant world, illustrating the ubiquitous nature of power and the difficulty of confronting privilege.

A colorful cast brings the apartment building to life. There’s the lawyer in Unit 4D who “had called screaming with fear about a water bug in the hallway” and the hedge-fund-portfolio manager in 6C who “drunkenly tossed his keys on the subway tracks.” The characters are what make Conell’s novel so affecting, perhaps none more so than Lily, the neo-liberal, anti-government, and anti-bourgeois retired voice actress. Though the novel takes place after her passing, Lily remains omnipresent, a voice of morality and reason to both Martin and Ruby. While both the father and daughter can at times come off as judgmental or even ungrateful, Lily guides them in the right direction. She grants Ruby the gift of her sagacious memory, and she narrates Martin’s life with sarcasm and love. Her spirit embodies the novel, mediating Martin and Ruby’s relationship and adding a humorous attitude toward the world.

Despite having Lily’s voice as guidance, Martin struggles more and more to maintain his composure as his mind flits from one job to the next—whether it’s unclogging a drain, getting rid of the strange woman who wanders into the foyer, or exterminating his beloved pigeons. Through Martin, Conell highlights some of the aches and pains of aging; thus we cannot help but cheer on his spirit as he fights back in small, meaningful ways, whether it’s breaking a tenant’s cup or farting into one of their meditation pillows.

Meanwhile, Ruby is left to reckon with the young woman she has become. Now face to face with Caroline, her oldest childhood friend whose palatial apartment will be the site of the eponymous party upstairs, Ruby confronts the truth about their friendship as well as her sense of shame and inadequacy. Conell deftly illustrates the way wealth, or the lack thereof, can shape a person: from the way Caroline refers to Ruby as “kiddo,” despite being the same age, to the “Holocaust-orphans-sisters-survivors running from Nazis” game that she insisted they play, Caroline serves as the embodiment of false modesty, of disingenuous empathy, and the desire of the bourgeois to romanticize struggle. As Ruby reflects on the years they spent growing up together, she recognizes that to Caroline she is a passing side character, inextricable from her economic status and a mere charity case whose misfortune Caroline can use to boost her own ego.

By alternating between Martin and Ruby as they circulate among their home, their beloved Natural History Museum, and their pasts, Conell manifests a tension so tangible that we are left on edge, desperate for some cathartic return. But in a tale that is as poignant as it is funny, Conell’s portrait of class division and privilege ultimately reminds us of the gaping disparities between our expectations and the harsh realities that often follow.