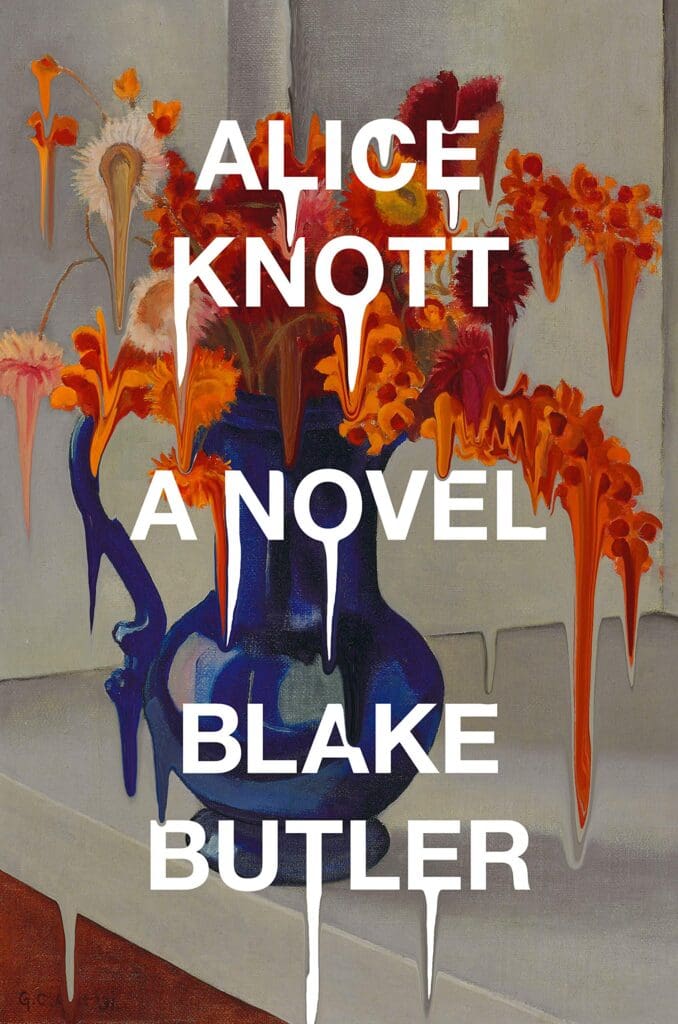

In his latest novel, Alice Knott (304 pages; Penguin Random House), Blake Butler defies the conventions of traditional narrative with a scintillating specimen of postmodernism. Alice Knott, the eponymous protagonist, is a reclusive heiress whose wealth rests in famous works of art purchased throughout the years. Alice spends her days in isolation, roaming the halls of her childhood home like a ghost, haunted by the memory of her late parents and mysterious twin brother, until a viral video reduces her life to shambles. The video captures the events of one cataclysmic evening when a group of anonymous art terrorists invade her home and, unbeknownst to her, destroy some of her priceless collection, leaving no explanation behind. Now inextricably linked to this “act of terror,” Alice finds herself ensnared in the web of an international conspiracy involving copycat incidents.

Across the globe, artwork is violated in seemingly random acts of frenzy: one man “pissed directly into the mouth of the second largest figure in Louise Bourgeois’s Three Horizontals”; someone else leaves van Gogh’s Sunflowers “spray-painted over in neon pink with the words THE SHIT OF LORD.” Alice, being the first victim in this string of crimes, finds herself as one of the primary suspects, as the media speculates about her reclusive lifestyle and ominous past. Meanwhile, as these senseless acts of destruction continue, Alice struggles to understand the foggy memories of her past and the obsessive paranoia of her eccentric family.

With a plot focused on artwork, Butler’s stunning and impressive wielding of language mirrors its content, as he writes with the same tenacity and calculation as a painter with a brush. Although at times his long sentences, and their lack of syntactical variation, seem nearly meretricious, the surprising bouts of humor add a clever, comedic overtone to an otherwise intense story. For instance, while the authorities in the novel struggle to understand the chaos befalling the art world, Butler illustrates the sometimes arbitrary and unclassifiable nature of art with a police officer who at one point states, “no, we do not understand what any one of the work of art itself was trying to say or even represent exactly…nor did it improve my experience of life on planet Earth as a known human.”

Within these responses to the vandalism—including a U.S. president who can only offer that he is “thankful to the lord above who blessed me with my power and influence, not to mention my good looks, and yeah my kids”—lies a ubiquitous truth about art to which we can all attest: sometimes it just doesn’t make sense; and as senseless and inexplicable as the vandalism may be, so appears the vandalized art. And yet, as Butler deals with the at times ludicrous and unexplainable side of artistic creation, he maintains that it is still, above all else, a courageous and indelible expression of humanity that cannot be reduced to the diminutive, no matter how others may try to.

Although at times Alice Knott can feel tedious, the vivid and poetic nature of Butler’s writing style ultimately proves engrossing. With the novel’s humor, arresting voice, and pastiche of conspiracy, art, and paranoia, Butler brings to mind the work of Pynchon and DeLillo as he explores the complexity of artistic achievement and the unreliability of our own minds.