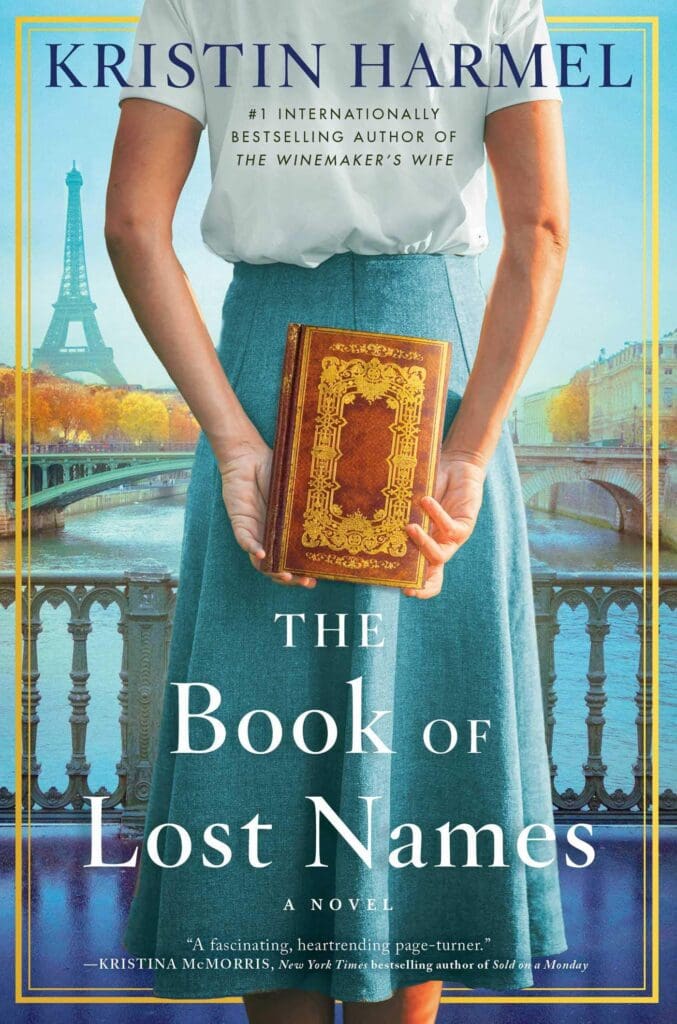

Kristin Harmel’s fifth novel, The Book of Lost Names (400 pages; Gallery Books/Simon & Schuster), is a tour de force––a stirring testament to stoicism and courage in the face of “nightmares of monsters dressed as men.” Harmel’s story takes readers back to Nazi-occupied France, where the protagonist, a young, willful Jewish woman named Eva Traube, forges documents for the hundreds of Jewish children to be smuggled from France to Switzerland. If caught, she’ll hang. The heartrending story grapples with the contortion of morality, of faith and hope under duress, and the inimitable power of love. The book jumps between Eva’s years as a forger in 1943––as she fights to remember and record the thousands of identities erased by the Nazis––and a graying Eva in 2005, as she fights to remember her own. The story begins when the 85-year-old Eva reads a New York Times article: an important book from her past has been rediscovered by a collector in Germany. The collector has found a curious code in its pages.

One night in 1943, there is a knock at the door of the apartment of Eva’s family, Poles who emigrated to Paris years ago. In what forebodes the fierce persecution of Jews in Vichy France, Eva’s dignified father is dragged away as she watches, paralyzed, from a nearby apartment. From here, the reader is propelled into the story, which is paced like a spy thriller but characterized by a tenderness such novels often omit.

Fleeing on false documents convincingly forged by Eva, she and her Mamusia (Polish for “mother”) land in the provincial town of Aurignon, in a part of France considered a Free Zone. While Eva learns to accept her father’s loss, Mamusia’s spirit is splintered––an agony Harmel describes with a searing touch. When she asks her daughter where her husband has been sent to, Eva tells her to the East, “to a work camp called Auschwitz. In Poland.”

Her mother turned away and moved to the window. “Which way is East?” Mamusia asked in a whisper, and Eva followed her gaze outside. They were facing away from the disappearing sun, and the sky ahead of them had already turned to thick molasses.

Harmel deftly captures the despair of their circumstances, the impenetrable distance to Auschwitz. Mamusia’s anguish soon results in Eva becoming the receptacle of her mother’s grievances: “You failed him,” she tells her, referring to Eva’s father. Their relationship, which Harmel shows with brilliance and sympathy, cracks under this weight. So, when Eva decides to fight along the resistance––forging documents for Jewish children escaping the roundups—Mamusia is aghast that Eva would put both their lives in even more danger.

“What happens when they come for us, too? When they take us east? Who will remember us? Who will care? Thanks to you, not even our names will remain.”

This shakes Eva—not even our names will remain—but she nonetheless begins forging documents, creating new names for children too young to remember their old ones. But in the hope that these children eventually will be reunited with their pasts, she encodes the real and fake names into an old religious text: The Book of Lost Names. From there, the novel launches the reader into a turbulent but heroic journey—one informed by Harmel’s fascinating research into forgers during World War II. Though fictional, the novel is heavily based on the lives of real forgers in France, giving added solemnity to the horrors and reverence to the characters’ courage.

“The world is before you,” James Baldwin said, “you need not take it or leave it as it was when you came in.” Harmel’s profound historical tale speaks to that admonishment. Eva’s acts of resistance are what are called for when confronting a system that devastatingly targets a group of people. It’s hard not see in Eva’s fervor to remember forgotten names the same urgency in the call to remember the names of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and so many, many more.