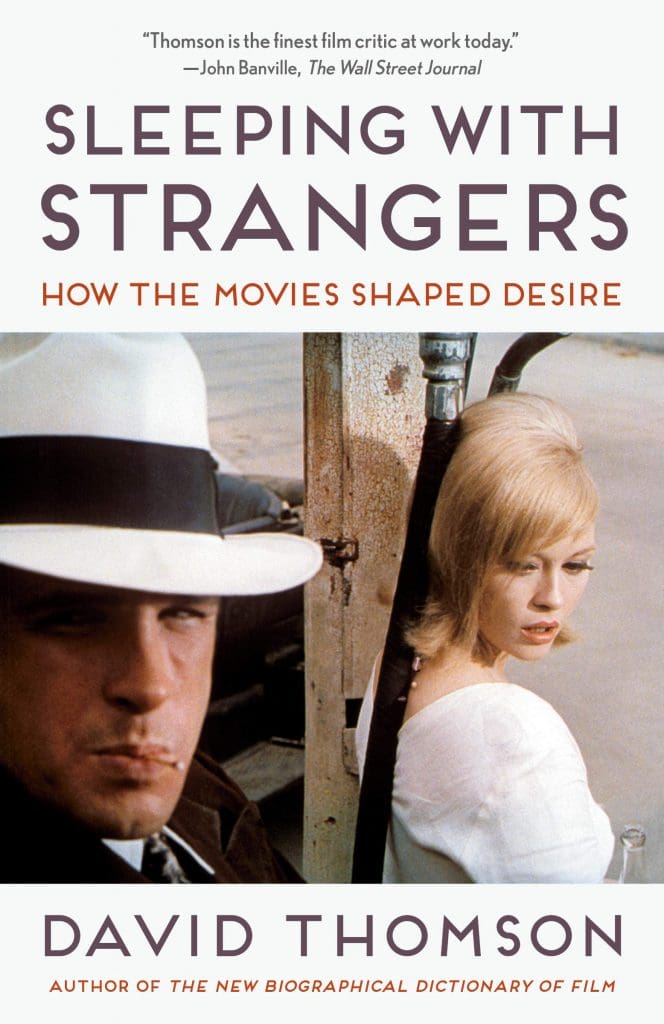

Reading the latest book by acclaimed film critic David Thomson, Sleeping with Strangers: How the Movies Shaped Desire (348 pages; Vintage), now out in paperback, one can’t help but suspect the book’s thesis may have changed over the course of its writing. A mixture of memoir, criticism, and film theory (“Why am I giving you history and memoir?” Thomson asks early on. “Because you cannot get close to movies without grasping the mindset in which they were received. When you go to the movies, you take your history with you. The fantasy is about you.”), the book was prompted by Thomson’s publisher, who wondered why there had never been an extensive account of the influence of the gay community on American moviemaking. While the book does cover this subject at length, Thomson perhaps sensed he was not necessarily the vessel for such a book—Thomson, age 77, is married with a wife and children—and shifted the title’s focus to include a highly personalized account of the ways in which Hollywood cinema has influenced American society’s views on sex and the institution of marriage, from Bonnie & Clyde’s Depression-era doomed lovers on the run to Richard Gere’s sexually ambiguous American Gigolo in Eighties neon, and beyond.

Yet Thomson acknowledges something happened while he was writing the book in 2017, something he couldn’t possibly ignore: the MeToo movement tore through Hollywood, as numerous power players found their sex crimes brought to light, including Thomson’s personal friend, director James Toback (who hasn’t had a narrative feature released in theaters since 2004). Thomson rightly sensed there was simply no way to discuss the male gaze of cinema without addressing the illicit behavior exposed by MeToo, and he even goes so far as to include a chapter that grapples frankly with his relationship to Toback: “Talking to him was suddenly disturbing, because it exposed foolish illusions I had held for years.”

One might expect a book with such a broad scope to register as unfocused, diffuse—but to read Thomson is to know you’re in the hands of a skilled writer, one who thinks deeply and who can move between topics in a manner that, if not effortless, at least leaves one charmed enough not to notice the detours. There’s a reason so many critics cite his massive tome The New Biographical Dictionary of Film as a “desert island book”; he has a knack for making us see our favorite performers in a new light while underscoring precisely what is so iconic or integral about their appeal, whether he’s discussing actors as disparate as Montgomery Clift (“He was a new ideal on screen, beyond his own grasp, strong but soft, pristine yet manly”) and Kristen Stewart (“impassive and luminous, capable of anything and convinced about nothing”).

In its blurring of personal experience, passionate movie-watching, and critical theory, Sleeping with Strangers raises several intriguing questions: did many Hollywood films of the Classical period throw a sidelong glance at the sanctity of marriage because these ostensibly heteronormative films were the work of so much gay talent? One might look to the work of directors such as George Cukor or James Whale, whose Bride of Frankenstein Thomson calls “one of the first films with a feeling for gender insurrection”; yet you’d be hard-pressed to find a more bitter treatise on the subject of marriage than 1940’s His Girl Friday, the work of director Howard Hawks, straight, and a film that “exploded the homilies of romance in favor of flirtation and the joyful cynicism of a journalism without much faith in its supposed grail, the Truth.” Those interested should find Sleeping with Strangers fairly comprehensive on the impact of gayness in cinema, including costume designer Travis Banton (The Devil Is a Woman) and dance choreographer Hermes Pan (Swing Time).

This subject carries a consequence: much speculation on the sexuality of various Classical movie stars, from Cary Grant to Burt Lancaster and many others. For those more interested in Grant’s romantic exploits in celluloid, not in the bedroom, these sections can feel like a bit of a digression, but it’s likely an inescapable area of discussion when writing about a time when Hollywood faced much more stringent censorship and any handling of queerness had to be heavily coded. For instance, Thomson is right to single out Clifton Webb’s portrayal of the villainous (and wonderfully named) Waldo Lydecker in 1944’s noir classic Laura—“Waldo is entertaining, and one of the sharpest spiteful minds in American films; he dominates the film”—while acknowledging that the notion of the jealous, homosexual killer would quickly become a harmful stereotype: “The un-normal do not make a habit of attacking the normal. That cruel energy usually works in the opposite direction.”

Was something lost when the pillars of Hollywood censorship crumbled, after films like Bonnie & Clyde and The Graduate ushered in more frank depictions of sexuality in 1967? It’s difficult not to think American cinema lost some previously essential quality, or at least its practiced flair for subtlety and inference. Thomson accurately points out how the movies themselves have been diminished as a cultural art form in our country, but he also doesn’t shy away from addressing the harm cinema has done to the culture, in perpetuating certain masculine codes and convincing audiences that happiness (as it appears onscreen) is just within reach. Thomson isn’t afraid to ask the question of whether the movies have sold us a false bill of goods. So few studio pictures are willing to approach the difficult work that comes after the “happily ever after,” the minuscule resentments and mounting pressures of maintaining a long-term relationship, let alone a marriage; they are content instead to trade in the excitement of seduction and conquest, leading many in the audience to expect such pleasures readily available in their meager day-to-day existence. How could such a bait-and-switch lead to anything but resentment? A resentment that is targeted not at filmmakers, by the way, but at those who share our beds. “Not everyone was going to get happy,” Thomson writes, “and it required a mass delusion to persuade everyone that the pursuit of happiness was a reasonable goal. Cinema was crucial in this con.”

If you’re a film buff, or simply a reader who maintains a passing interest in Classic Hollywood, Sleeping with Strangers feels like being in great company; passionate and erudite, Thomson takes genuine stock of how American cinema has portrayed the complicated terrain of human sexuality, while acknowledging that, in the wake of MeToo, the industry is likely to change—and that change in the medium is both a constant and, in this instance, deeply necessary.