In the early 1900s in St. Petersburg in Russia, a group of passionate young poets came together and formed a poetic movement they called Acmeism. Its object was to strip away the florid symbolism then standard in Russian poetry, and create poems based on “the word itself.” Osip Mandelstam and Anna Akhmatova were two of the most famous of these poets, but were they around today, they would welcome Jane Hirshfield into their coterie. Her stark, powerful poems are crafted so simply they seem effortless. Constructed largely of nouns and verbs, the very things the Acmeists valued most, it’s hard to understand how they manage to evoke such a range of emotion. And yet they do, with a voice that at times seems like an old world prophet, at times like a Zen Master.

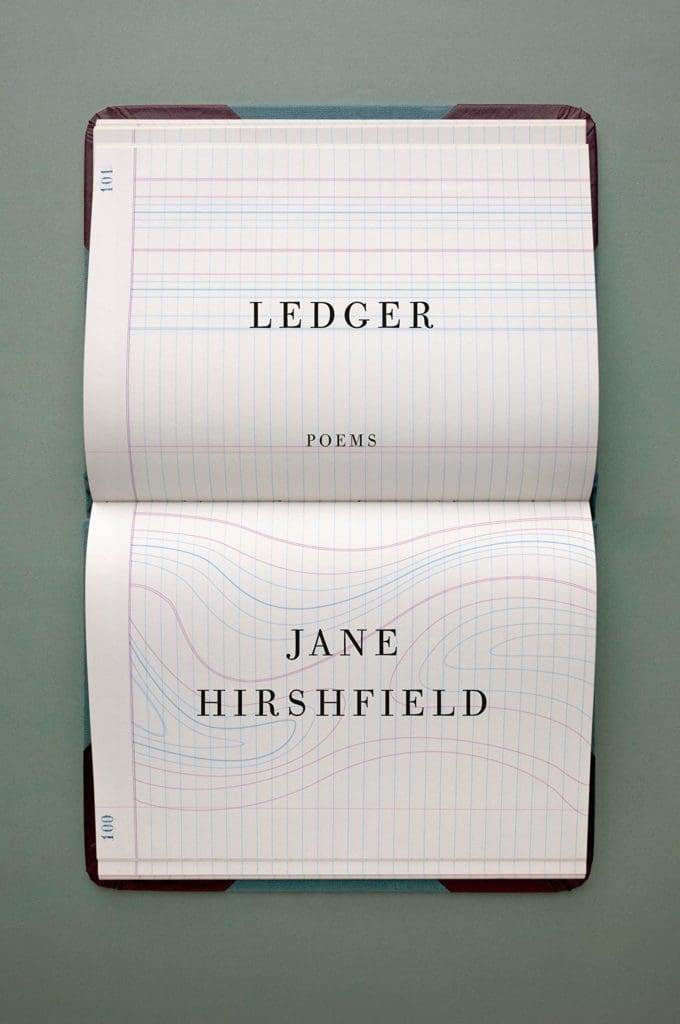

Several poems in Ledger (128 pages; Knopf), written after and partly in response to the 2016 election, have become anthems of protest. You may be familiar with “Let Them Not Say,” a litany that starts: “Let them not say: we did not see it. / We saw,” and goes on to its burning conclusion. The poem “On The Fifth Day,” a response to the order that scientists not speak of certain facts without approval, follows this same pattern of simply listing what could not be spoken “the scientists who studied the rivers / were forbidden to speak / or to study the rivers,” ending with “They spoke, the fifth day / of silence.” Unlike many other political poems, these have a quiet force, all the more powerful for their calm exposition—they unfold with what feels like an inevitable logic and build with a power that deepens with each stanza. In these poems, Hirshfield, a Zen practitioner, strikes the match to the doused robes of protest; this work will be anthologized, read and reread.

But they are not the full story of Ledger, aptly named as an accounting of life as we know it with its beauty, pain, chilling indifference. The title poem makes this explicit:

One liter

Of Polish vodka holds twelve pounds of potatoes.

What we care about most, we call beyond measure.

What matters most, we say counts….

Throughout this book the poet reckons the cost of human being, what is lost, what remains. The poem “As if Hearing Heavy Furniture Moved on the Floor Above Us,” captures this perfectly:

As things grow rarer, they enter the ranges of counting.

Remain this many Siberian tigers,

that many African elephants. Three hundred red-legged egrets.

We scrape from the world its tilt and meander of wonder

As if eating the last burned onions and carrots from a cast-iron pan.

Closing eyes to taste better the char or ordinary sweetness.

Here you see the rhythm and imagery that are so skillfully employed to create a profound effect in so few words. The elision of articles compresses the power of the concrete images, which heighten the image of the “tilt and meander of wonder,” a line few poets could weave successfully into a poem. The “char of ordinary sweetness” is the perfect metaphor for the message of this poem. If I were teaching a class on imagery, this poem would be in it. You could talk for a long time about the skillful construction, the absence/presence of the poet, the diction.

Ledger is Hirshfield’s ninth book of poetry (she also has three books of essays, two of translations, and has edited an anthology of sacred poems by women). Her unique voice is not brand new, but honed, sharpened. Many of these poems are short, like almost like koans. Many of the longer poems are a series of short epiphanies. Here are just a few, scattered through the book. First a description of a tree “not prunable not treatable not to be propped.” The poem describes its absence:

And so.

The branch from which the sharp-shinned hawks and their mate-cries.

The trunk where the ant.

The red-squirrels’ eighty-foot playground.

A few poems further, a different image of absence:

As the front of a box would miss the sides,

the back,

The grief of the living

misses the grief of the dead.

Or the image of “Cataclysm:”

Fish unschool,

sheep unflock to separately graze…

The turtles and moonlight?

Their long arrangement is over.

What emerges as one reads this book is a sense of mourning for what’s lost, and a piercing delight in what is left. By calling attention to the facts and figures of loss, by offering up a reckoning, Ledger literally as well as figuratively reminds us of what counts. This is perfectly expressed in this couplet from “Nine Pebbles:”

Sixth Extinction

It took with it

the words that could have described it.

There is personal accounting here, too—poems titled “My Glasses,” “My Wonder,” “My Dignity,” and poems addressed to the little soul. Hirshfield, so unlike most contemporary poets, is as comfortable in talking about the soul as the cast-iron pan.

Hirshfield’s sly humor is like a little salt in the cake, bringing out an essential sweetness, an acceptance of being a flawed human in dark times. Hirshfield, even at her most prophetic, never sets herself apart. This is summed up in the short poem “Like Others.”

In the end,

I was like others.

A person.

Sometimes embarrassed,

sometimes afraid.

When “Fire!” was shouted,

some ran toward it,

some away—

I neck-deep among them.

Perhaps, like Akhmatova, Hirshfield will be recognized for her poetic witness. The prophetic quality of the counting of loss is reminiscent of “Requiem.” For us at this moment, Ledger provides the comfort of good poetry in dark times.