Too many literary biographies are a waste of space–a cut-and-paste pastiche of previously published materials, random interviews, and unselectively edited quotes, put together in the apparent rush of getting from A to Zed and be done with things. The funeral is more important than what preceded it.

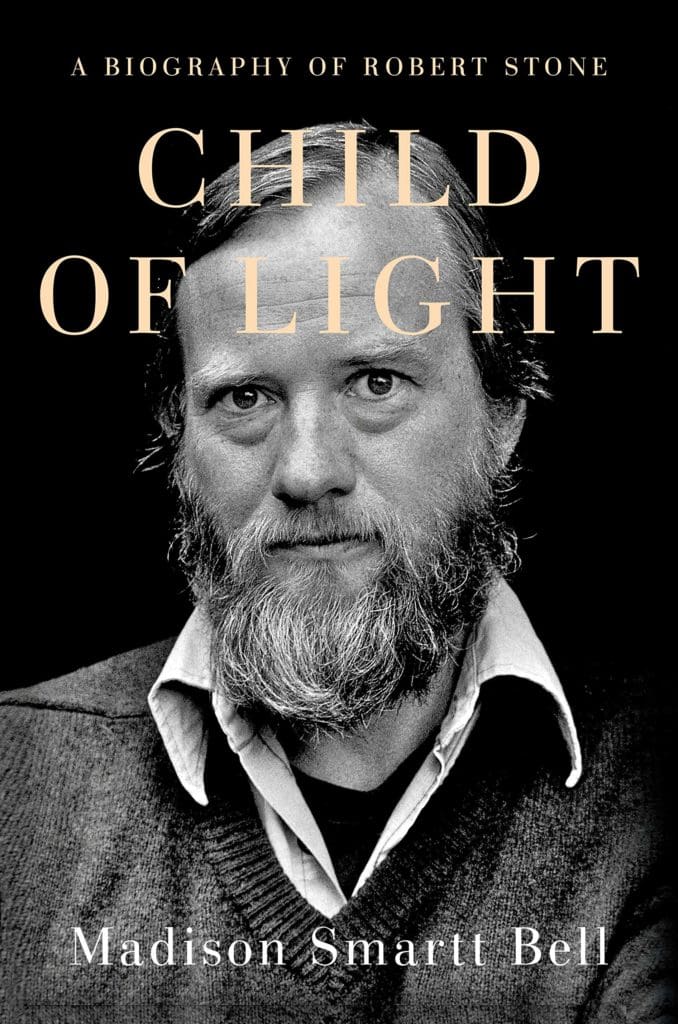

Madison Smartt Bell largely avoids these obstacles in Child of Light (588 pages; Doubleday), his masterly new biography of Robert Stone, in which he adheres to the Joseph Conrad dictum that Stone liked to quote: “Fiction must justify itself in every line.’’ Bell is also the editor of The Eye You See With, a selection of Stone’s nonfiction, and a Library of America volume gathering Dog Soldiers (1974), A Flag for Sunrise (1981), and Outerbridge Reach (1992).

Stone called himself a “theological’’ novelist, struggling with the notion of faith, largely rejecting his Catholic-raised boyhood. It’s something of a miracle he survived his early years, raised by a mentally ill mother—the two were sometimes reduced to sleeping on the roof of a Manhattan apartment building—and dodging the clutches of child protective services, which he found even less appealing.

Between stints as a copyboy at the New York Daily News and enrolling at New York University, he found a way out through the mentorship of the late poetry professor M.L. Rosenthal, who recommended him for the Wallace Stegner writing program at Stanford.

Stone being Stone, he did not embark on the academic path directly, venturing first, in 1960, to New Orleans with his new, just-pregnant spouse, Janice—described elsewhere as the “patron saint of writer’s wives.’’

Broke and scraping bottom, he found work in a factory, and then as a census taker in public housing projects, material which he later foraged for his first novel, The Hall of Mirrors. This dystopian, prescient tale of a right-wing radio station, WUSA, whose backers want to use the platform to start a race war. The central character, Rheinhardt, an out-of-work musician, works as a DJ there, parroting the company line with self-lacerating mockery, yet another in a panoply of unreliable, suffering narrators who populate Stone’s fiction.

He was accepted into the Stanford program’s class of 1962-63, a move that would help him professionally (Stegner offered a glowing blurb for the eventual publication of A Hall of Mirrors) and challenge him psychically, through his association with unlikely fellow enrollee Ken Kesey, who introduced him to the questionable benefits of LSD, and, ultimately, to the Merry Pranksters.

Although never prudish about chemical alterations, Stone sensibly went on his own path, eschewing the cross-country trip recorded in Tom Wolfe’s record of the Pranksters journey, to concentrate on his fiction. As Bell puts it: “Baroque extrapolation of delusion was becoming part of Stone’s stock and trade as a novelist, but he was a long way from buying in to what Kesey and his inner circle were trying to become.”

But as accomplished as The Hall of Mirrors was, winning the William Faulkner Foundation Award for notable first fiction, it was exceeded by his second novel, Dog Soldiers, a seminal account of the ravages of the Vietnam War, informed by Stone’s time as a correspondent for a short-lived London underground paper. (It was adapted into a surprisingly effective film, though Stone and director Karel Reisz hated the title change, taken from the Creedence Clearwater song, to “Who’ll Stop The Rain.’’).

A heroin smuggling deal gone bad drives the pulpy plot; it’s a parable, and a warning. Stone found he had to go to Vietnam to write about America. He’s merciless about himself, and his principal character, John Converse, a weak-willed writer who recruits Ray Hicks, a Nietzschean buddy, to move the scag. Captured by government agents, who have Marge, Converse’s wife, and Hicks on the run, he recalls a former 101st Division medic named Ken Grimes, who returns to Vietnam as a noncombatant and “carried candy to give people when his morphine ran out.”

Sometime later, Converse learned from Jill that Ken Grimes had died in the Ia Drang Valley, reading Steppenwolf. His death was one of the things Jill cried about. She regretted meeting him, she said. It made her tired of living, and that was a dangerous way to feel.

Converse felt differently. Grimes had provided him with an attitude which he publicly pretended to share—but which he had not experienced for years and never fully understood. It was the attitude in which people acted on coherent ethical apparitions that seemed real to them. He had observed that people in the grip of this attitude did things which were quite as confused and ultimately ineffectual as the things other people did; nevertheless he held them in a certain—perhaps merely superstitious—esteem.

The self-laceration continues:

After the fact, he had written a feature story about Grimes in which he had conveyed grief and rage at the waste of a life. The grief and rage conveyed were entirely professional, assumed. At the core of Converse’s reaction to Grimes’ life and death were a series of emotions which were not grief or rage and did not make him tired of living—they were compounded of love, self-pity, even pride in humanity. But his story as written was false, facile, a vulgarization—that was, after all, his business.

It gets worse from there. Stone’s trademark was his refusal to soften the blow.

As Antonya Nelson put it, reviewing his last story collection, Fun With Problems, for the New York Times and contrasting his work with Hemingway, or even Raymond Carver: “If you thought that Raymond Carver’s men would be happier if they only had a little help—if they’d been educated, cultured, programmed, employed in white-collar rather than blue-collar jobs, sent to talk therapy and prescribed anti-depressants—well, Robert Stone is here to tell you that none of that guarantees anything.”

Bell tells the tale of Stone’s life, in chapters evenly devoted to his works, which include such major achievements as A Flag for Sunrise, Outerbridge Reach, Children of Light, and Damascus Gate, examined in counterpoint to the unique circumstances in which they were written.

He takes a deliberately flat, noncommittal approach to describing Stone’s addictions to alcohol and painkillers. He traces the course of the usual hustles—various academic positions to which he gravitated for financial security, writers’ conferences where he was prone to misbehave, and the infidelities that he (and Janice, to a considerably lesser extent), were prone to. It’s a reconstruction, not deconstruction, of the life and works of this resolutely realistic author.

The story of two trips the two men took to Haiti, the setting for Bell’s epic novel, All Souls’ Rising, has a rococo flavor. On the second visit, he finds himself briefly abandoning the hobbled Stone in order to attend a Vodou ceremony, then has to fast talk him out of the country after he loses the pink slip needed to immigrate back to the States.

But despite the tenuous position of acting as anyone’s Boswell, particularly a close friend, Bell reserves judgment. The result is a book that serves as an act of friendship, scholarship, and devotion.

Some of the early response to this biography has been a little depressing.

One reviewer, while noting his virtues, asserts that Stone has “faded from cultural conversation,’’ unlike such contemporaries as Pynchon, DeLillo and Carver, citing Stone’s failure to be mentioned in a couple of recent literary histories.

And a notice in the Wall Street Journal, snottily headlined “Globe Jotter,’’ resurrects an antique controversy over whether some of the material in Outerbridge Reach, the tale of a sea voyage that turns fraudulent, was drawn in part from a British nonfiction account of a sailor who’d undertaken a similar journey. The narcissism of small differences, indeed.

Stone contented himself with a dignified reply: “Fiction’s province is the moral obligation. Its function is not to detail the actual world, but to create a parallel one. Image by image, phrase by phrase, through artifice and evocation it must then make that world at once credible and meaningful…No great work is remembered for its plot, that clumsy replication of ‘real life.’”

The survival of this great American author’s work should not, and cannot, be quantified in Google searches, let alone academic references. He shook off the demons that beset him, and left us with a richer, more recognizable world. It wasn’t always pretty, but it was always truthful.

As Stone liked to say, recalling the weary adage of those who had been to Vietnam, and seen the metaphorical elephant: “There it is.”