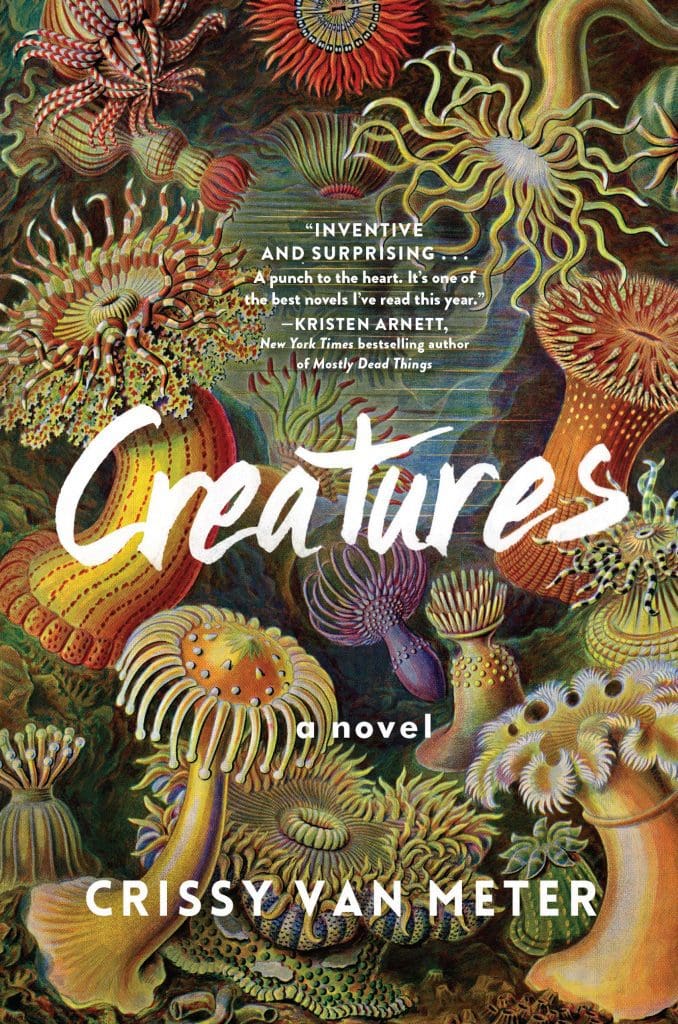

Set among the seasons and temperaments of a fictional island just off the coast of Southern California, Crissy Van Meter’s first novel, Creatures (256 pages; Algonquin Books), explores the world of Winter Island through the eyes of its narrator, Evangeline. Her story begins just three days before her wedding as she awaits her fiance’s return from the sea, even as a storm grows on the horizon and a whale’s carcass lodged deep in the harbor fouls the air. With her fiance possibly lost at sea and with a rotting whale to dispose of, Evie must also make do with the uninvited presence of her mother. For Evie, everything hinges on these three days—but soon the narrative becomes dislodged in time, inhabiting the narrator’s life far into the past and the future.

Throughout her life, as evidenced by her research notes and meditations on the evolution and survival of sea creatures, Evie turns to the ocean for the answers to hard questions. Of the “52-hertz whale,” an individual whale of unidentified species whose songs scientists have tracked for decades (the songs always going unanswered), Evie notes:

You could end up like the loneliest whale in the sea if you are not careful. If you live on an island with a mother who doesn’t want you and a father who wants too much, you might scream and no one will hear you. The kind of mammal who can’t even articulate emptiness. If you want to survive, you must learn another language made of mysterious sounds, full of your own answers, and grow a new mouth and a new heart, and keep swimming to the light.

In this way, Evie’s life is inextricably bound to the sea. It’s a relationship that develops at a young age as her father—an alcoholic who peddles the island’s popular strain of marijuana—teaches her to love the ocean and to see the magic in their little corner of the world. Her mother also tells her of the ocean, but unlike Evie’s father, she does not feel tied to the island and is in and out of Evie’s life, often without warning. Perhaps this absence is partially to blame for Evies feelings of being at once drawn to the rest of the world but obligated to stay put. At war with indecision, Evie experiences a lifetime of being left behind. She grows up full of longing, often hoping for people and emotions to return to her. But as she endures again and again the weight of her loneliness, she comes to question what it is that makes her stay on Winter Island.

Both lyrical and succinct, Creatures is acutely immersed in its setting. Van Meter transports the reader to Winter Island, capturing not only the volatile and brutal nature of the ocean, but the wonder and awe of it, too. The author’s grip on this physical space, together with the distinctiveness of Evie’s voice, allows for daring temporal leaps through the narrator’s life. Though the shifts in time in conjunction with Evie’s research notes can prove jarring and feel at times a bit performative, on the whole Van Meter is able to master this complicated structure for a powerful story.

Creatures, too, is a book about compromise—about learning that vulnerability and love walk hand in hand, as do joy and heartbreak. As the people closest to her prove unreliable, Evie comes to understand that some wounds never heal completely; they can be salted over with seawater and hope, but they’re left exposed when the tide pulls back. With her oceanic research as her guide, Evie gives the reader all of her memory, her love and her loss as she searches for an answer.