As October comes to a close, the Bay Area gears up for perhaps its favorite holiday: here’s hoping your Halloween involves more treat than trick! In the office, we’re also offering a seasonal Staff Recommends—here’s a roundup of the works we’ve been reading, watching, and listening to:

Scout Turkel, Intern: My music taste is defined by habit rather than preference. What makes a song good isn’t necessarily genre or content, but its capacity to fit into my rigorous and specific listening routine: for about a month at a time, I play one song, and one song only, on repeat, over and over again. Few songs hold up––most become unlistenable or annoying after a few goes. And of those select tracks that do withstand more than a handful of consecutive plays, hardly any are able to sustain me for the duration I demand. The song has to be versatile––joy-sparking but also a bit sad, appropriate for a long, crowded BART ride home or an early morning cross-campus trudge to class. It has to be sexy and danceable, galvanizing enough for chores and cleaning, calming enough to study with, and, more basically, just generally likable. I’ll be playing it all the time, so wide-spread appeal is important; I have two roommates and over one-hundred housemates, the hope is that they enjoy (or at least can tolerate) it along with me.

Scout Turkel, Intern: My music taste is defined by habit rather than preference. What makes a song good isn’t necessarily genre or content, but its capacity to fit into my rigorous and specific listening routine: for about a month at a time, I play one song, and one song only, on repeat, over and over again. Few songs hold up––most become unlistenable or annoying after a few goes. And of those select tracks that do withstand more than a handful of consecutive plays, hardly any are able to sustain me for the duration I demand. The song has to be versatile––joy-sparking but also a bit sad, appropriate for a long, crowded BART ride home or an early morning cross-campus trudge to class. It has to be sexy and danceable, galvanizing enough for chores and cleaning, calming enough to study with, and, more basically, just generally likable. I’ll be playing it all the time, so wide-spread appeal is important; I have two roommates and over one-hundred housemates, the hope is that they enjoy (or at least can tolerate) it along with me.

I’ve had many of these songs come and go over the years, but one stands up against the nonstop-listening test like no other. “Coconut Kiss” by Niki & The Dove is the soundtrack to all my seasons, and all my tasks. My breakups and my triumphs. My bad days and my dance parties, alone or, more usually, in the kitchen of my giant communal home, friends and peripheral acquaintances alike all writhing on the half-mopped floor to the synthpop anthem of our dreams. Maybe the dream is just mine, but Swedish duo Malin Dahlström and Gustaf Karlöf make me feel otherwise. Dahlström’s voice is powerful but a little eerie, high-pitched and slightly crooning with a disco-y pace and flirtation. I won’t pretend to know anything about this band––I don’t. I haven’t even really engaged with the rest of their 2016 album beyond its genius title, Everybody’s Heart is Broken Now. Which is true. “Coconut Kiss” isn’t quite a climate disaster ballad, but it’s hard to turn away from the possibility it offers for collective mourning; the planet is hurtling towards an uninhabitable state, and we all, in a truly worldly sense, are being forced to feel the crushing heartbreak of our doom together, perhaps for the very first time. And yet, in the true fashion of our times, it’s also campy. And sweet. And sensual. Karlöf’s lyricism is objectively sad, but the pop, electro-rhythm of the track begs you to dance. “I am a loner / And I paid my dues / And I don’t depend on nothing / Or no one / I am a loner / All confused / Waiting for that rainy day / While I spend my time / Walking in the sunshine”––believe it’s about climate change yet? If you don’t, well, that’s okay. It took me a few hundred listens to land on that take.

More fundamentally, “Coconut Kiss” is about heartache and the defensiveness that comes with that violation, be it carried out by the corporations warming our planet to its premature end or a first love who stopped feeling the same way. The answer it offers to this loneliness isn’t redemption, but something more removed, even cynical: “Swinging in my palm tree / Cause I love coconuts / I’m drinking Coconut Kiss / And you don’t get to know me / You don ‘t get to know me…” I love that impulse; it’s not that the mystical and heartbreaking “you” doesn’t know me, or shouldn’t know me, but rather that they aren’t allowed to. The isolation isn’t necessarily empowering, but it is a choice. As everything goes up in flames, we retain a little say in how the end plays out, sipping our syrupy, boozy punch in what may be the last palm tree on earth.

Even at the end of all things, planetary or not, Niki & The Dove puts a sleepy, warm haze over all of our sadness and confusion. “I like to / watch the world / The world is looking good today / It’s almost like I ‘m sleeping / I pull my head back to the sun” whispers Dahlström in her intimate drawl. There’s still some pleasure in watching, which might be a terrible thing to say. But it feels true when she sings it, and truer still when I hear it for the hundredth time, on the kitchen floor clutching my mop, now a mic, or too close to another body on the five o’clock commuter train, somewhere under the bay.

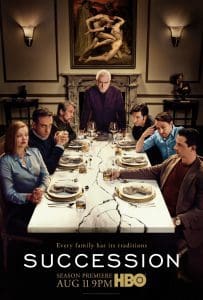

Sophia Stewart, Intern: Succession is a difficult series to distill into so few words. The show is so many things at once. It’s an amalgam of many genres: corporate thriller, family drama, workplace comedy. It pairs the course repartee of Veep with the aesthetic of Billions (that is, badly behaved rich people in New York). And as for premise, Succession borrows a bit from Arrested Development: a flawed family with a company to their name, law-evading patriarch, adult children vying for power.

Sophia Stewart, Intern: Succession is a difficult series to distill into so few words. The show is so many things at once. It’s an amalgam of many genres: corporate thriller, family drama, workplace comedy. It pairs the course repartee of Veep with the aesthetic of Billions (that is, badly behaved rich people in New York). And as for premise, Succession borrows a bit from Arrested Development: a flawed family with a company to their name, law-evading patriarch, adult children vying for power.

I know what you’re thinking: who wants to watch rich, white, entitled people scheme for hours on end, especially at a time like this? Believe me, the thought crossed my mind, too. But Succession goes beyond the constraints of its premise to deliver something that is devilishly clever, emotionally resonant, and thoroughly addictive. Each episode is hearty, filling—stuffed with gripping drama and caustic wit. Dysfunction is the series’ organizing principle, and boy, does Succession do dysfunction well.

So here’s the story: the Roy family, who reign over a media empire, are a family in name alone. In reality, they’re a business operation. Unburdened by familial love or loyalty, the Roys are ruthless and conniving, conspiring against each other as they paw at power. The drama that plays out among the family members is downright Shakespearean—betrayals, back-door deals, attempted patricide. There is Kendall, the scorned heir; Roman, the twisted manchild; Siobhan, the focused striver; and Connor, the idiosyncratic recluse. And of course, pulling the strings is Logan Roy, CEO and father, in that order.

What makes Succession work is the thrill of seeing these personalities collide. These are terrible, terrible people, and watching them mistreat each other is truly delicious. (At one point, an observer of the family tells Kendall, “Watching you people melt down is the most deeply satisfying activity on planet Earth,” and I have to agree.) We’re like anthropologists, studying these hapless, hopeless miscreants. The Roys are monsters, products of late capitalism, and what a joy it is to watch them run loose in Manhattan. But just because the Roys are despicable doesn’t mean they’re soulless. They still succumb to the pains and pressures that come with their high-stakes lives. And we are there to witness it all, as bystanders, voyeurs, or something in between.

Succession alternates between satisfying schadenfreude and heartrending tragedy, often within the same episode. Yes, we feast on the Roys’ suffering, maybe even delight in it. But we also suffer alongside them: no matter how removed from reality they may be, their humiliations, addictions, and rejections, in some sense or another, mirror our own. And that, dear reader, is the success of Succession: the Roys can disgust us all they want—we’ll love them just the same.

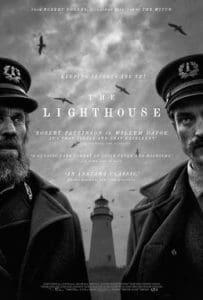

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: Ever since Robert Eggers’ name floated around a possible remake of the 1922 silent film classic Nosferatu, I’d imagined what The Witch director might do with a visual aesthetic inspired by German Expressionism. With Egger’s latest film The Lighthouse now in limited release in the Bay Area, I no longer have to wonder: the spirit of Weimar Era filmmaking is present in every shot of Robert Pattinson’s wide, startled eyes. While the Nosferatu remake appears to be on the back-burner for Eggers (maybe someday?), his latest is a black-and-white, shot-on-35mm chamber piece about a grizzled lighthouse keeper, played by Willem Dafoe, and his new assistant (Pattison) in New England circa the late 1800’s.

Zack Ravas, Editorial Assistant: Ever since Robert Eggers’ name floated around a possible remake of the 1922 silent film classic Nosferatu, I’d imagined what The Witch director might do with a visual aesthetic inspired by German Expressionism. With Egger’s latest film The Lighthouse now in limited release in the Bay Area, I no longer have to wonder: the spirit of Weimar Era filmmaking is present in every shot of Robert Pattinson’s wide, startled eyes. While the Nosferatu remake appears to be on the back-burner for Eggers (maybe someday?), his latest is a black-and-white, shot-on-35mm chamber piece about a grizzled lighthouse keeper, played by Willem Dafoe, and his new assistant (Pattison) in New England circa the late 1800’s.

Beset by ill weather, their post begins to stretch beyond its scheduled four week tenure and the two men—dynamically portrayed by Dafoe at his spittle-on-beard best and an equally game Pattinson—find their relationship (and their sanity) tested by isolation, the elements, and the almost sensual lure of the lighthouse’s beacon itself.

I feel somewhat guilty trying to articulate my thoughts on this film after only one viewing—very early into The Lighthouse I knew I absolutely needed to see it again, if only to inhabit once more the wave-battered world Eggers has conjured here, one where seabirds carry the souls of long dead sailors and mermaids appear like sirens on the rocky shore. Much as in The Witch, Eggers’ influences here feel as literary as they do cinematic: one pictures an antique bookshelf where Herman Melville sits comfortably alongside H.P. Lovecraft. The dialogue registers as period accurate and studiously researched; much of the viewing experience involves listening intently to the performers, a reminder that part of the pleasure of cinema can be simply experiencing sonorous dialogue in the hands of actors who can truly rise to the level of the material. This is never more apparent than during the many scenes in which Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson have cause to curse each other out: their exasperated tirades are bawdy, vulgar, and represent some of the best “setpieces” I’ve seen in theaters all year.

To say much more about The Lighthouse might give away some of the film’s many surprises and delights—I’m also underselling just how damn funny this material is—but rest assured the movie is worthy of the serious viewer’s time before it departs from theaters like a steamboat headed back to the mainland. Reports indicate Eggers’ next film will follow a 10th century Nordic prince on a quest for revenge; after impressing with both Puritan folk horror in The Witch and the nautical hypno-drone of The Lighthouse, Eggers seems poised to do much the same in the land of the Vikings. I’ll be purchasing a ticket.

Laura Cogan, Editor: Selecting which book to read next from the mile high stack and even longer list is an inscrutable process for me, one that is more emotional and intuitive than reasoned. I want to read them all, so why this book, today, but not last month or last year? I can’t say. I think there may be material to analyze here, perhaps not totally dissimilar to the way dreams reveal simmering, subterranean concerns. I find myself reluctant to interpret, but it is interesting to note areas of synchronicity or divergence. The two books I read this month, for example, are different in most ways except this: they both revolve around family life, the most profound fears of parenthood, and the outer edges of what we can fully understand about what transpires at home–especially our own.

Laura Cogan, Editor: Selecting which book to read next from the mile high stack and even longer list is an inscrutable process for me, one that is more emotional and intuitive than reasoned. I want to read them all, so why this book, today, but not last month or last year? I can’t say. I think there may be material to analyze here, perhaps not totally dissimilar to the way dreams reveal simmering, subterranean concerns. I find myself reluctant to interpret, but it is interesting to note areas of synchronicity or divergence. The two books I read this month, for example, are different in most ways except this: they both revolve around family life, the most profound fears of parenthood, and the outer edges of what we can fully understand about what transpires at home–especially our own.

First I read Victor LaValle’s The Changeling, an expansive and engaging fairytale blending contemporary and classical ideas of trolls and witches. LaValle’s smooth prose and compact chapters gave me the thoroughly enjoyable sense of being told a story of adventure and enchantment by a practiced and authoritative craftsman. Yes, there were moments when the plot felt strained or central ideas over-explained, but it never felt worth breaking the spell of story to stop and dwell on them.

Next I picked up The Perfect Nanny by Leila Slimani, a book I’d been both drawn to and dreading. Over two tense days of reading I inhabited every taut sentence, every deft character portrait, every nuanced and loaded interaction between Louise (the nanny) and her employers and their children. Slimani is careful not to vilify the parents (painting a sensitive portrait of the working mother), while seeking to create context (personal and societal, structural) for Louise’s break down. The book raises thorny, un-resolvable issues of class, reminding us that such issues persist even when, with the best of intentions, we turn a blind eye. Ultimately, there can be no explanation or understanding for the devastating act of violence Louise commits: it is unthinkable. But Slimani turns the impulse to ask “why” and “how” into an exercise in humanity.