Considering Alfred Hitchcock’s early movie The Lodger in light of his complete oeuvre—a task that can happen only anachronistically—gives us the old master minus two elements that furnished his films with the trappings of modernity amid an otherworldliness: color and sound. Where scores and palettes might have made reliable signposts, into this silent black-and-white film step in cinematography, action, tone, and shadow, drawing up a London that has more affinities with the cramped darkness of the theater than any brick-and-mortar city. Forced to eschew [musical?] crescendos—then a fact of the format, but an active exclusion in later films like The Birds—Hitchcock, in his self-declared stylistic debut, stakes out the obsessions that would define his career. They appear regularly and with an absurd reliability; almost everything about the director’s later films that snags viewers, critics, and scholars—sexuality, formality, urbanity, banality, perversion, off-kilter sensibilities, those vertiginous qualities Roland Barthes spoke of as the un-locatable “third meaning” of films—makes an appearance. Each is as interesting for what it says about the man as it does about the libraries of reels he left us, and more so for the way in which each tic is quietly rehearsed and unveiled. Nothing in The Lodger reeks of a checklist; nothing has the comfort of a formula. If, to enlist a dead metaphor, the beginning of a career is the opening of a door, then behind that door stands the film’s title, that ominous figure: his eyes as sharp as his demeanor, his knife-like shadow slicing through the frame, wrapped not just in scarves but in the fog that peels voices from bodies.

*

Hitchcock didn’t dynamite through a mountain to make the first film he would characterize as his own (“you might almost say,” he told François Truffaut, “that The Lodger was my first picture”—though it was the third film he had directed); he stepped through a tunnel someone else had bored. The Lodger, like so many of his works, is an adaptation of a novel, in this case Marie Belloc Lowndes’s 1913 psychological thriller. For its focus, Belloc Lowndes would look back ten years before she started writing, to the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888 that left a chain of butchered women across London. Even in Hitchcock’s version of her story—and is it really her story, after all?—the sense of repetition is strong, even dizzying, despite his decision to reverse the fate of the titular character. The film opens with the mechanical heartbeat of industrialization, the programmatic flashing of a sign that reads TO-NIGHT: GOLDEN CURLS, enticing the murderous as much as the lecherous to the vaudeville theater where the naïve Daisy Bunting, the film’s sweetheart, makes a living off her locks. Against a suitably black background, the credits hover, led by an animation of a detective’s silhouetted against a swath of creamy light. What happens next is predictable enough, and after the scream, the objectifying shot of terror on the woman’s face as her life ends, we see the murderer’s cloth-wrapped face as he departs. A ring of citizens and police beleaguers her, none too startled to pass up the opportunity to ogle a corpse. Hitchcock gives us no sense of where these Samaritans were when during the murder; the harsh lamplight slathers everything with a morgue-like quality.

Things begin bleakly in The Lodger. Not for the assassin slinking through the alleys, nor for the first beautiful cadaver he leaves in his wake, but for the voyeurism of those in the vicinity of this first on-screen death. The film begins with a statement about morals and manners that manages to be telling without being didactic, one that marks the gestation of an impulse that, like so many others, would grow to be a limb of Hitchcock’s body of work. The weirdness of the scene stains the rest of the film, paints it with a haze: one begins to suspect the motives of the police, of the intimidated public, and, of course, those of the lodger. Even Daisy’s family, whose ostensible goal has been to keep their daughter safe (or at least alive), risks bad faith. The possibility of truly “harmless” semi-sexual fun, the sort of flirtatious occupation Daisy has taken up, also sustains a blow to its legitimacy; in a later scene, where the lodger watches Daisy parade herself at her place of employment, the echoes of lust and violence, interspersed throughout, overlap. No move or countermove is insignificant. The Lodger would—according to some critics, among them William Rothman, author of the canonical Hitchcock: The Murderous Gaze—serve as a template for many of the director’s later works; Murder!’s beginning and ending, Rothman observes, parrot those of its forerunner. At the same time, some see in the film a 20thcentury rejuvenation of classical culture, like Lesley W. Brill, who interprets it as a version of the Persephone myth.

If The Lodger gave rise to the conditions of the films that followed it, then London provides The Lodger with plausibility: the macabre enters the story not as an isolated phenomenon, but as the social constitution of the city itself, the very thing, per the rules of one theory of plot, the macabre is supposed to breach. Is justice for The Avenger—so says the killer’s calling card, adorned with a cryptic triangle—and his victims (presuming, for whatever reason we do, that the killer is a male) possible? There are good reasons to ask this, just as when we see Cary Grant as Thornhill in North by Northwest remove the knife from Townsend’s back, thrust by his situation into the part of the slayer he is not. The Lodger is anxious about representation and resolution, but paradoxically, it is also resigned, if not apathetic; the spectacle transpires, and the world moves on. But not before “MURDER: WET FROM THE PRESS” graces the screen and a gleeful paperboy, selling copies of block-headlined papers, has a chance to speak. “Always happens Tuesdays,” his intertitle card reads, “that’s my lucky day.”

*

Speech is an odd thing in silent film, where its absence reduces it to another component of body (or is it bodily?) language. For this reason, when characters appear to talk, it can remind us of speech’s physicality, can render it alien. The Lodger is no exception; the frames of dialogue sprinkled throughout are strangely similar to the flashing sign marking the film’s opening and closing scenes—somehow foreign, somehow unnatural, but explanatory, as utilitarian and artificial as captions. The actors in turn gesticulate, sulk, emphasize, and emote regardless of the situation. Animated no matter the tenor of the conversation, exuberant even in fright and despair, they come off as over-determined mimes—believable enough for their fidelity to a standard vocabulary of moods, but also engaged in acting only because we are engaged in viewing. The audience, in other words, is implicated at every point. Not only are we party to the peeping Tom-like masses and their treatment of sight as the only means of verification, but we also authorize the film to proceed as it does. In doing this, we tie the ends of the circle together, because by looking—and our own looking comes off as unfavorably as that of the crowd gathered around the first girl to meet her end—we also give up our privilege to be disgusted by the crowd, the press, and the paperboy whose gawking we might claim to disdain.

“The mystery of the Avenger—who and what he is—is also the mystery of what the camera really represents,” writes Rothman, for if there is such a thing as modernism for cinema (an art born while modernism writ large was already having its heyday), it starts with Hitchcock. Meanwhile, the morning edition runs down the chutes; the typewriter chatters; we gape at the characters’ mouths as they open and close. Hitchcock’s cameo, which occurs very early on, the first instance of what would become one of his signatures, is directly related to this addiction to communication or failures thereof: the director sits in a newsroom, his ear to a telephone whose transmissions we cannot hear.

*

It’s worth noting that this first cameo happened, so apocryphal accounts have it, because the actor slated for the role of telephone operator never showed up. He may have lost the job of a lifetime, but in doing so he promoted the development of a tradition that would outlive him. Hitchcock has two cameos in The Lodger, reappearing toward the end of the film to save the statue-faced Ivor Novello—playing Jonathan Drew, the lodger—from the mob about to lynch him. At this point, the film’s plot, however elliptical or self-reflexive, is in need of some explication, though recollecting the plot gets us about as close to the whole of the film as sheet music does to the performance of an opus. But by the time one chaos becomes intelligible, another erupts to push it back into unintelligibility, and an attempt at tracking these destabilizations may be helpful.

A short time after the film’s opening salvo, when Daisy mocks, perhaps ignorantly, her fellow coworkers for their fears of being targeted by The Avenger, the atmosphere seems to have somewhat improved. The town appears to have regained its wits and the prospects of death at the hands of a hair-crazed stalker seem less likely—especially when several showgirls, including Daisy, take to pinning brunette tufts of hair over their ears when they go out (“Safety first!”), just one moment of blood-laced laughter in the film. Whatever equilibrium Daisy’s lightness succeeds in bringing back, though, is soon erased by a knock on the door of her parents’ home. In perhaps the film’s most mythical, paradigmatic scene, the lodger steps forth from the fog with the pomp and iciness befitting the villain of a Greek epic: the identity, and evil, of this man is near doubtless. In large part he matches the description of The Avenger provided by the few who glimpsed him escaping the scene of that first murder—tall and, with his jaw cocooned in cloth, ghoulish. His eyes, severed from a discernible face, roam from one side to the other as he surveys the foyer; he makes no pleasantries and, when he finally speaks, takes an inordinate amount of time to inquire about the room for rent. By offering a month’s pay in advance, he defers any financial worry about his solitude and aloofness: yet another move by which Hitchcock has us thinking about the sources and limits of human motivation—how far little slips of paper can go to compensate for danger.

There is, nonetheless, something straightforwardly funny about this scene, something affected about Novello that inclines one to class his idiosyncrasies as quirky, even if apparently malicious. After this second puncturing of the film’s pretensions, life in the Bunting household begins another slow regression to normality. Daisy and her love interest, Joe, an amiable but oafish policeman who thinks he might snag The Avenger, continue to behave as if undaunted by the increasing probability of Daisy’s endangerment as more showgirls are found dead—all killed on Tuesdays and abandoned with The Avenger’s characteristic notes. Meanwhile, the unnerving man who arrived—the man who requested a glass of milk, bread, butter, and to be left alone—paces in his room with such force that the chandelier bolted to the floor below him begins to sway, serving as a weathervane of sorts by which the Buntings are prompted to pay attention to the mysteries of their tenant as they flare up and subside. So bothered by the images of blonde women on the walls of his room, the lodger turns them face-down and requests they be removed; relief turns into the translation of one frustration to another, though, when Mrs. Bunting sends up towheaded Daisy to take them away.

The lodger’s paranoia is one signal of many. The more we become acquainted with him, the more he takes on not just the outward appearance of The Avenger but the habits appropriate to someone on the lam: the pacing continues, he locks his belongings in a cabinet in his room, and his reaction to Daisy when he first meets her—“Beautiful golden hair,” he mouths—strikes one as the fetishistic ramblings of the insane. The story, of course, offers more than this, but before contending with its arguments and suggestions there must be some acknowledgment of this initial resemblance between The Avenger as we imagine him and the lodger as we see him. On Hitchcock’s part, this might be read an indictment of both the evidential process by which we form opinions as well as a dethroning of the audience: when the lodger is vindicated, when we find that he is not, in fact, The Avenger, we must confront the realization that our estimation of the man was no better than that of the characters who rashly and unfairly doubted his intentions. The lodger picks up a fire poker; a moment of suspense passes before he uses it, tritely, to poke the fire. For Hitchcock, the audience is another mob, another tyranny to be reckoned with, even if it’s true that, out of no small spite, he has set us up for failure.

*

Hitchcock’s writers hardly, if ever, get their due. So it’s unsurprising that critical as well as popular writers generally neglect to consider the implications of the fact that the The Lodger is a presentation of Belloc Lowndes’s novel (as well as a play she co-wrote, titled, with almost hilarious acuity, Who Is He?). Hitchcock’s 1951 Strangers on a Train takes as its springboard the novel of the same name by Patricia Highsmith; for Strangers, he even recruited Dashiell Hammett to orchestrate the dialogue. Hammett passed the task on to Raymond Chandler, but a dispute with Hitchcock finalized Chandler’s departure from the production. I should clarify that by “Hitchcock’s writers” I mean, in addition to the novelists from whom he mined material, the screenwriters who provided the more concrete distillations and actualizations of those materials. The Lodger’s script was written by Eliot Stannard, who supplied the text for Hitchcock’s first two movies; Alma Reville, the assistant director, was his wife. Joseph Stefano adapted Robert Bloch’s novel Psycho for the production of the same name. The Birds is in large part the work of Evan Hunter, hired by Hitchcock to convert to the screen Daphne du Maurier’s eponymous novella from her 1952 collection of short stories, The Apple Tree; Hitchcock and Hunter—also known by his pseudonym, Ed McBain—collaborated and revised the script, but surely writers like Hunter deserve more due than they receive in discussions of Hitchcock’s projects. Family Plot, the director’s last film, took its script from Ernest Lehman’s conception of the 1972 novel The Rainbird Pattern by Victor Canning. The list of individuals—other geniuses, whether they were writers or cinematographers or producers or advisors—to whom Hitchcock is indebted is too long to recount here. Suffice it to say the director’s name, though it stands for the brilliance of one man, also stands for the brilliance of a whole host of people whose names have now vanished into mist.

The Lodger owes much of its power to its actors—Ivor Novello, firstly (whose pre-existing stardom, Hitchcock worried, had slanted the film), but also June Tripp, known as “June” during her lifetime. Tripp’s role in The Lodger was preceded by work in two other films: 1926’s Riding for a King , and, six years earlier, René Plaissetty’s reworking of the 1915 crime novel The Yellow Claw by Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward, then writing under the pseudonym Sax Rohmer. Her filmography leading up to The Lodger parallels that of Hitchcock’s, who had only directed two films prior, each a year apart: 1925’s The Pleasure Garden, and 1926’s now-lost Mountain Eagle, both silents. But while Tripp would leave acting after narrating Jean Renoir’s The River and taking some part in Lewis Milestone’s adaptation of Les Misérables in the early 1950s, Hitchcock would go on to upset and remake cinema for the next few decades. But he would take no insignificant lessons from her. On the one hand, Daisy is the stereotypical young woman, portrayed through a sexist lens; her very occupation, after all, is to look good for men who can and will pay to look at her. On the other, her character is a commentary on the political agency of women, their ability to love who they choose—in the face of resistance from their families and designated suitors—and their right to retain control over their sought-after bodies. No matter how blind she is to her environment, no matter how naïve, she is also the only person with heart enough to believe Novello is innocent, a thesis that, however foolish, turns out to be true. And the scene where Novello knocks on the bathroom door while Daisy is in the tub brings forth the motif of the “vulnerable and defenseless” (to quote actress Janet Leigh) bathing woman—a motif that, 33 years later, would instill a phobia of showers in any viewer of Psycho.

*

So if the lodger is innocent, just who is The Avenger? There are two answers, one spelled out explicitly by Hitchcock, the other made implicitly. After a series of harrowing and conspicuous incidents, including one where Mrs. Bunting watches the lodger sneak out and return on the same night another showgirl is murdered, the identity of their guest seems fixed; Mr. and Mrs. Bunting and Joe, Daisy’s policeman wooer, have grown more and more suspicious of the lodger and his budding relationship with Daisy. Provoked by the thought of being spurned, Joe follows Daisy to her late-night date with the lodger; a confrontation ensues, and Daisy tells Joe there is no longer anything between them. After the two leave, Joe considers the course of recent events—his zealous tracking of the killer, his too-strong pursuit of Daisy’s attention, the bizarreness of the lodger—and persuades himself that Novello is The Avenger. What the two officers who accompany Joe on his warrant-authorized search of the lodger’s apartment find is hardly exonerating: the locked cabinet holds a black bag containing a gun, a map of the murders, and a photograph of an attractive blonde. The lodger breaks down with what Joe and the officers take to be guilt over his crimes, and they attempt to arrest him, though he manages to free himself into the murky night.

His guilt is not guilt, though, but grief. Finding the lodger alone in the fog, Daisy listens as he explains his story. He is not The Avenger, but the brother of one of the killer’s first fatalities; the photograph in the suitcase was that of his sister, whose death at her coming-out ball—undertaken beneath the veil of a suddenly blacked-out dance hall—caused her mother to die of shock. The loss of his mother and his beloved sister sent him into an anguish that soon manifested itself as rage: hence the resemblance between him and the murderer he sought retribution from—a grotesque and mournful irony. What, then, does The Avenger, whoever he is, hope to avenge? Hitchcock doesn’t reveal this, though he leaves no doubt, via flashback, that The Avenger operated with precisely the same procedures—including leaving a calling card emblazoned with his epithet—when he took the life of the lodger’s sister as he did when he hunted the showgirls. Still, the more we learn about Novello’s character, the less we realize we know about the Avenger. As film historian John Orr writes, the imaginary “is not the real, yet in filmic terms can be just as immediate as the real,” a fluctuation central to modern cinema—a dictum certainly true in the case of The Lodger, a film darkened by the shadow of a killer it never meets.

His guilt is not guilt, though, but grief. Finding the lodger alone in the fog, Daisy listens as he explains his story. He is not The Avenger, but the brother of one of the killer’s first fatalities; the photograph in the suitcase was that of his sister, whose death at her coming-out ball—undertaken beneath the veil of a suddenly blacked-out dance hall—caused her mother to die of shock. The loss of his mother and his beloved sister sent him into an anguish that soon manifested itself as rage: hence the resemblance between him and the murderer he sought retribution from—a grotesque and mournful irony. What, then, does The Avenger, whoever he is, hope to avenge? Hitchcock doesn’t reveal this, though he leaves no doubt, via flashback, that The Avenger operated with precisely the same procedures—including leaving a calling card emblazoned with his epithet—when he took the life of the lodger’s sister as he did when he hunted the showgirls. Still, the more we learn about Novello’s character, the less we realize we know about the Avenger. As film historian John Orr writes, the imaginary “is not the real, yet in filmic terms can be just as immediate as the real,” a fluctuation central to modern cinema—a dictum certainly true in the case of The Lodger, a film darkened by the shadow of a killer it never meets.

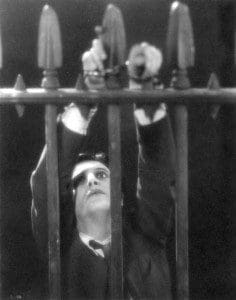

By the time the puzzle of the lodger approaches resolution, we’ve lost sight of the curious, though surely important, ethical quandary evoked by the killer’s name: who gets to practice revenge? Whose anger counts? And whose sins? Novello’s character calls for distrust and even outright fear at first, and then pity as his history comes to light; it is not altogether inconceivable that The Avenger, however wicked his acts, was likewise warped by such a horror as renders him deserving of some empathy. But we can never know this, not only because obtaining such knowledge has undesirable consequences—it requires we forego the systems on which so much open-and-shut justice is based—but because it isn’t feasible; at one point, the lineage of tragedy, of crime and punishment, affront and vengeance, frays into oblivion. However potentially unfair the persecution of Novello and the capture of the real Avenger (which happens just in time to save Novello’s life when he and Daisy are chased by a flock of vigilantes who suspect him to be the killer), the safety of society necessitates they be persecuted and captured. But Hitchcock, knowing this—and disdaining, even to a fault, the vox populi—still refuses to participate in the shameful cycle. The actual Avenger, the origin of the movie’s fundamental problem, is arrested off-screen with no fanfare, an absolution of the innocent that ignores the uglier howls of populism when, however justified, such populism traps its enemy. If anything, the heinousness of the crowd is overemphasized; the lodger, fleeing with Daisy from the lynch mob, snags his handcuffs on a wrought-iron fence and hangs from it like Christ, threatened not with crucifixion but bludgeoning. These nameless judges form the second, more implicit component of avenging referenced in the killer’s alias: they embody social fury and some distant idea of a trial, though what unfolds more resembles an appetite for retaliation than a respect for due process. But this is also true of Joe, whose aggravation at the bond between the lodger and Daisy prompts him to sweep the lodger’s apartment—justice becomes indiscernible from revenge, and love from penalty. And it is also true, in a roundabout way, of the lodger himself, whose scrupulous search for his sister’s murderer molds him into the murderer’s likeness.

*

By the end of The Lodger, there are few reasons to consider it a horror film in the typical sense: it fluctuates between comedy and tragedy, putting forth avenues for each. Taken prima facie as a work of horror, though, it represents all of what would eventually become Hitchcock’s most famous manipulations of the genre—distortions and corruptions of the natural order, a lack of confidence in the intelligence and competence of the police, the depiction of crowds as riven with groupthink and fascism, the fragile division between spying and observation, and the panic of being the wrong person in the wrong place at the wrong time, especially if this means being oneself. Add to this an inability to trust one’s own perceptions and the cramped melancholia of domestic spaces, and the recipe for Hitchcockian madness is almost complete; what matters is the proportion of the ingredients and the element peculiar to each film. In The Lodger, domestic spaces take on a notably sinister ambience, whether they be the snarled innards of the city or the kitchen of the Buntings’ house. In the latter, the walls are only thick enough to prevent sight, but not much else: eavesdropping abounds, as Mrs. Bunting, plagued by the Sisyphean torture of housework (to borrow a phrase from Simone de Beauvoir)certainly finds time for it. At times London seems a rat maze; at other times, an open field, as the partitions do little to keep people apart. In its amorphousness it resembles Penthesilea from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, a city whose residents are never quite sure whether they are within its walls. For a few moments in the film, even, Hitchcock rolls the camera from underneath a glass floor to give us the impression of standing on the first story of a house, imagining what those above us are doing, a move reminiscent of Fritz Lang’s M and its manipulation of reflective surfaces. An interest in domestic spaces would reemerge later, too: the lead-in to the final attack scene in The Birds, for instance, when Tippi Hedren shines her flashlight on the darkened stairwell before entering the fateful room. “The modern mind becomes ever more calculating,” wrote Max Weber in The City, and this is, in part, an aphorism The Lodger testifies to, with its characters constantly seeking veracity amid deceit, searching for new ways to see.

I have left something out: the film’s subtitle—or, more truly, the second half of its title. The Lodger only points toward the man at the movie’s hollow center; A Story of the London Fog invites the cold-blooded buildings of London, the drugged tension of a city with one foot in modernity and another in the past, into the film and the theater, the latter which becomes just another compartment in its hive-like catacombs. The perennially unsettling aspect of fog is, obviously enough, how it obscures sight and effaces perception: fog turns solid objects to phantoms, casts a blanket over the familiar. For all the differences between the London of The Lodger and the Bodega Bay of The Birds, the fog remains static (if not disobedient; rumor has it that Hitchcock had to tint some frames of The Birds gray). I had the good fortune to see The Lodger screened at the Pacific Film Archive last month, where Judith Rosenberg accompanied the film with a hypnotic whirlpool of a piano score; the presence of an analog musical instrument (is that the phrase we should adopt?) in place of a digital soundtrack distorted the boundary between the this-world of the audience and the that-world of the film, bringing its life, and its danger, closer. Such a performance also makes one wonder whether Hitchcock was right to score some of his most popular films; he added the score for Psycho after initially wanting no music for the scene, but became convinced that Bernard Herrmann’s string piece “The Murder” heightened its effects. On the other hand, the scene in which Hedren shines her flashlight on the stairwell in The Birds is silent, flavored with that universal, animalistic trepidation that accompanies forays into unlit spaces.

I have left something out: the film’s subtitle—or, more truly, the second half of its title. The Lodger only points toward the man at the movie’s hollow center; A Story of the London Fog invites the cold-blooded buildings of London, the drugged tension of a city with one foot in modernity and another in the past, into the film and the theater, the latter which becomes just another compartment in its hive-like catacombs. The perennially unsettling aspect of fog is, obviously enough, how it obscures sight and effaces perception: fog turns solid objects to phantoms, casts a blanket over the familiar. For all the differences between the London of The Lodger and the Bodega Bay of The Birds, the fog remains static (if not disobedient; rumor has it that Hitchcock had to tint some frames of The Birds gray). I had the good fortune to see The Lodger screened at the Pacific Film Archive last month, where Judith Rosenberg accompanied the film with a hypnotic whirlpool of a piano score; the presence of an analog musical instrument (is that the phrase we should adopt?) in place of a digital soundtrack distorted the boundary between the this-world of the audience and the that-world of the film, bringing its life, and its danger, closer. Such a performance also makes one wonder whether Hitchcock was right to score some of his most popular films; he added the score for Psycho after initially wanting no music for the scene, but became convinced that Bernard Herrmann’s string piece “The Murder” heightened its effects. On the other hand, the scene in which Hedren shines her flashlight on the stairwell in The Birds is silent, flavored with that universal, animalistic trepidation that accompanies forays into unlit spaces.

Sound or silence, there is much to be afraid of in The Lodger: the histories of strangers and the prospect of letting them in, for one. And the hideousness to which vigilantes can stoop as they become less interested in fairness than reprisal, not to mention the helplessness of the police to function as anything more than an extension of public sentiment. The film is also preoccupied with what motivates individuals to act, and whether or not the cataclysms they have suffered by chance give them reason to act in less-than-ideal ways—and, what’s more, whether we should accept these reasons. But taking into account Hitchcock’s general trickiness, and the mischief that saturates his cinematic technique as well as his knotty grasp of narrative (it is, twistedly enough, the paperboy’s announcement that the Avenger has been caught that keeps the mob from beating Novello to death), the paragon of fear in The Lodger is not to be found in any identifiable demon, but in the shape-shifting, untrustworthy—fog-like—nature of things, even happiness. As Michael Wood notes in the London Review of Books, the film’s scariest moment is not one of its compulsions to return to claustrophobic flats or the dim, stone veins of London, but its end, where the acquitted lodger and Daisy embrace. Is the love, Wood asks, that draws the two together—or Daisy’s doe-like contentment as she slackens in his arms—really all that different from the force that drove The Avenger to take the lives of so many women? Why is revenge so often a tool of love, and why does love so often look like revenge?

Neither question is easily resolved; in any case, both unstitch whatever wounds the film had pretended to seal. Daisy and the lodger, now more handsome than dark, refute the warlike strategies foisted on them by the circumstances of their courtship by embracing—but this gesture of consummation is as much a gesture of surrender, a release of defenses. And so we are sent, swirling, back into the cloudy swamp of the possible where the behavior of psychopaths resembles that of good citizens and no one’s yellow-haired daughter is safe. In the background, meanwhile, the sign that sputtered in the beginning of the film still blinks, and London, no brighter for their smiles, looks brooding as ever.