If you’ve dined at any number of swanky Bay Area establishments, you might have unwittingly enjoyed your meal in a restaurant designed by one of the few people who is as well known and well respected for his fine art as for his commercial work. Michael Brennan has designed the interiors of such San Francisco hotspots as Farallon, Zero Zero, Fleur de Lys, and Bruno’s, and Alameda’s Miss Pearl’s Jam House, as well as Revival in Berkeley. He’s painted murals for many more places, too, including the Cliff House (also in San Francisco).

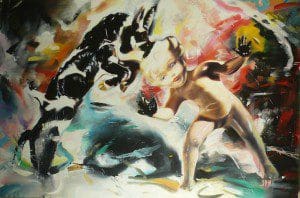

ZYZZYVA’s Winter ’11 issue features images of some of Brennan’s smaller-scale works. For these paintings, he often chooses as his subject small figurines and children’s toys. Brennan magnifies them in both scale and import, revealing affection for the mementos of childhood, but without sentimentalizing them or glossing over the sometimes-sinister tone these objects assume when considered out of context. Coating them in oil to add sheen, Brennan casts these toys and figures against abstract or ambiguous backgrounds, rendering them in near photographic realism. The results can alternate between the playful and the nightmarish, and recall the feeling of certainty nearly every child has that his toys “come to life” when no one’s looking. We talked with him about his work at his SOMA studio in San Francisco.

ZYZZYVA: How did you get started doing these paintings?

Michael Brennan: … I was just looking at this little figurine, a little boy locking heads with this goat. It just seemed so weird to me. I read this article that said that 80 percent of pet owners feel like they alone have this completely special psychological connection to their pet that no one else has. 80 percent of people feel this way. It was funny, because then I started noticing them (the figurines). And I saw this little figurine of this little boy with his head joined with a goat, and it just seemed so funny to me. That’s how I started doing these figurine paintings.

Z: You don’t do anything obviously dark with the children’s toys or figurines you paint, but there is something macabre about them.

MB: I think there is a perceived innocence about figurines and toys and dolls. As a child it was kind of scary for me to look at these. It has to do with a lot of things. When I was about ten I had this huge crush on my neighbor’s sister; she was about 16. She was the coolest girl I’d ever seen. She had this red sweatshirt, a boyfriend with this rally hot car, just the coolest. She had this figurine on her nightstand. I told my friend, her little brother, “Don’t tell your sister, but I want to go in there and draw that figurine on her desk.” Because to me, if I could draw it, I had ownership of it. I remember sneaking in there for four or five days in a row and just drawing this thing up, and I don’t know why. I think I felt if I could draw this thing and make it mine, that it would be some small connection to her. There’s definitely some strange, scary thing about them.

Z: Do you think that it’s because they’re not in the context of a child’s world? Taken out of context, they turn?

MB: Actually, most of these figurines are for adults, although I have worked with children’s stuff. I was obsessed with Doctor Seuss as a kid. I did this one painting of a Doctor Seuss character, which I consider to be a self-portrait. I think it has to do with the fact that they’re molded plastic. I used to make models of things. I started with cars and airplanes. In the ‘60s they came out with these molded Surfer Bob and Rat Fink figures. They were molded, really sculpted stuff … it just seemed to me that everything looked so soft, but was hard. I was obsessed with Salvador Dali when I was a kid, and he had this whole theory about hardness versus softness as something erotic. And these figures, they look like they could be plush toys but they’re in fact hard. They’ve got this sheen to them.

Z: Your paintings of porcelain almost look like they could be mixed media collages, photographs of figures placed against painted abstract backgrounds. How did you get so good at rendering textures?

MB: Well, when I was a kid everyone else was taking trumpet lessons, but I told my dad I wanted to take art lessons, oil painting lessons, specifically. I think I was in the third grade. We found this woman in San Jose. She had this little shack in her backyard, and I think she was German. She smelled like turpentine and oil paint and I thought that was so great. I always drew… cars, Rat Fink … as soon as I started painting that’s all I wanted to do. I didn’t even want to draw anymore; I just wanted to paint. Everybody now says, “Why don’t you do some works on paper so you could make some money, instead of always trying to sell a $12,000 painting?” It doesn’t interest me. There’s a focal point where the paint becomes the image–it is really magic to me. I keep trying to play with that. You step closer, past a certain point, and it’s just paint. But you step back again and it’s the image. I’ve started to paint the shadows of the paint if there’s a splotch or a drip, just kind of playing with a bunch of layers of perception. There’s the paint, there’s the paint casting the shadow, and there’s the paint making the image.

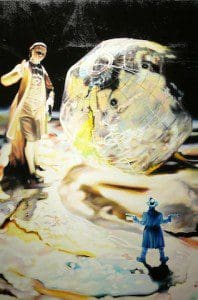

I don’t know why I keep painting these (figurines). I guess it’s just the stuff that’s always been around. Like these army men. They’ve been around all my life. When I was a kid we’d play with them, burn them, torture them, and now I paint them. I’m drawn to them, I guess, because of the way they are perceived, what kind of emotion we associate with them. An army man’s face is pretty stern. There’s something behind all my paintings. I had a teacher in college who told me, “Unless you have something to say, don’t paint. Just get another job. Your job is to comment on society or say something personal.” That’s why I hate decorative art. I mean it’s great for restaurants, obviously. But for easel paintings, you have this incredible opportunity to say something—take advantage of it! This one (points to a large painting of a porcelain figurine of an eighteenth century man facing off against a toy soldier before a globe) is called “Outlaws.” It’s about colonization. But I do think the actual painting of it is as important as what you have to say.

Z: Sometimes it seems like art schools focus more on making sure you have something to say than on the technical aspects.

MB: Well, it’s funny, because everyone is getting back into realism. I went to this lecture at the art institute, looking at all the students’ work, and they’re trying to do realistic stuff, but nobody can paint. Why don’t they learn the basics of painting and then do whatever they want with it? It just seems like everyone wants to get there really fast, get their message out without going through the formality of learning to render…

Z: You said you didn’t like drawing. How do you compose your images? Do you draw by painting?

MB: I do a thumbnail of what the painting should look like, where the figures should go. Once that’s set in my mind, I just start. On the canvas I just draw the outline to get the scale right.

Z: What is the connection between painting and designing restaurants? Is there one? Or is it just that a visual person can do both?

MB: I never took a design class, but I bartended for fifteen years and basically learned how a restaurant runs. It’s strange–if you don’t pursue it, it happens and is a success. I just started by doing murals…designing little ones on the side. It snowballed. It just got bigger and bigger. People just keep calling. I just got a call from a restaurant in Chicago; they wanted me to interview for it. I went, “You know I’m not an architect, right?” and he said, “You’re not?? Never mind….”

I dunno. You get to a point where you can’t even afford your own paintings–you just think to yourself, “Whoa, I couldn’t afford to buy this.” For me that was really strange to think about—I’m creating this thing that I can’t even afford to buy.

Read more from Larissa Archer at her blog, larissaarcher.com.

One thought on “Studies in Sinister Toys and Figurines: Q&A With Michael Brennan”