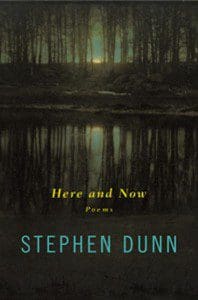

Whenever a poet as preeminent as Stephen Dunn releases a new corpus of material, the potential for failure can’t help but manifest itself. Some might fear that the book, having come from an author who has already attained a pinnacle of critical achievement (Dunn won the Pulitzer Prize in 2001 for Different Hours), will turn out to be a footnote compared to the works that preceded it. Still others might stifle an otherwise solid book with narrow expectations or preconceptions. Yet Dunn’s most recent publication, Here and Now (Norton; 112 pages), is anything but stillborn, an object all its own—rather than a repetition of a song everyone has heard before, the collection is a new and surprising symphony altogether, a cornucopia of techniques bearing Dunn’s trademark style and approach. And while they are not innovative in any experimental sense of the term, the poems manage to amplify some less-noticed but integral elements of the writer and professor’s work.

Whenever a poet as preeminent as Stephen Dunn releases a new corpus of material, the potential for failure can’t help but manifest itself. Some might fear that the book, having come from an author who has already attained a pinnacle of critical achievement (Dunn won the Pulitzer Prize in 2001 for Different Hours), will turn out to be a footnote compared to the works that preceded it. Still others might stifle an otherwise solid book with narrow expectations or preconceptions. Yet Dunn’s most recent publication, Here and Now (Norton; 112 pages), is anything but stillborn, an object all its own—rather than a repetition of a song everyone has heard before, the collection is a new and surprising symphony altogether, a cornucopia of techniques bearing Dunn’s trademark style and approach. And while they are not innovative in any experimental sense of the term, the poems manage to amplify some less-noticed but integral elements of the writer and professor’s work.

Many of the pieces in Here and Now adopt a characteristic first-person narrator often found in previous Dunn collections. This figure serves as a linchpin of sorts—holding the pieces’ perspectives together, lending their fragments congruency. This narrator has much to say, or, at least, much to point out about all manner of subjects. But despite the apparently mild demeanor of this observer poem after poem, the insights never come off as tired or stultified. Dunn’s fascination with the world, quiet though it may be, is ongoing. Combined with the fact that his poetic intelligence allows him room to not merely refrain from conclusions but to suggest them as well, one of the foremost qualities of these pieces is their collective and uncanny ability to undermine systems of certainty, to point out the slipshod construction of various artifices.

At their strongest, these poems are muffled manifestos: coded winks at the reader, words muttered under breath. Gone with the turn of a page, their implications and inflections of meaning—or confusion of meaning—linger. Consider the multi-layered glances at social hierarchy and class injustices in “The Revolt,” in which Dunn imagines seizing a corrupt banker’s house:

…The waste in his pipe, his very own waste, well,

you might say I’ve liberated it, let it out.

My plan is to be sitting in his chair when he returns

from where he’ll have found himself knee deep.

If you want to be part of this, perhaps bring a friend.

I’ll meet you in the garden where I wait without shoes.

Who knows what we’ll do when his room is ours.

Tongue-in-cheek analysis of class politics continues in the immediately adjacent poem, “Little Good Song,” which reads in its entirety:

It’s good to sneak up from behind

to the front, good to sit

for a while in the best seats.

When the rich show up it’s good

to explain how they’re mistaken

and cite the small, unreadable print.

The meek are ready, you tell them it says,

the meek have come to take their seats.

In these moral explorations, truth extends beyond a Manichean duality of rightness and wrongness and into near-infinite shades; Dunn, unlike many of his colleagues, is unafraid to address social tensions in political terminology. Still, it is impossible to tell what, if any, side he is on. “A true inner world is often revealed by style and sensibility as much as by what appears to be confession,” said Dunn in a 2004 interview with Guernica. Then later: “I’ve always thought of my first-person speaker as an amalgam of selves, maybe of other people’s experiences as well.” While Here and Now might feel on the whole like a mosaic of confessional shards fused together to make an object of beauty, Dunn’s pieces, upon closer readings, oblige themselves to nothing except the intrigue of possibility. They contradict, compliment, and even combat each other in the form of a book-length conversation. But whatever they do, whatever they “are,” they are always interesting. These aren’t confessions in the sense of an Anne Sexton or a Robert Lowell—of the post-1950s school that vaunted individual experience, written plainly and honestly, to be the paramount articulation of poetry. On the contrary, Dunn manages to embrace the prerequisites of both that aesthetic and its antithesis. These are confessions, but the confessors are nameless; they are not coy, but sharp, and they are honest without constraining the abilities of the imagination.

And there is much to be said about imagination in this collection. Hypothetical realities are created and destroyed, their purposes made vital and then obsolete, within the course of several stanzas. In “The Melancholy of the Extraterrestrials,” an alien species recounts what he, she, or it sees as the paradox of humanity: a lack of intelligence paired with kindness. And in “Prufrock Later,” Dunn transforms what might otherwise have ended up as a wastebasket-bound draft of an undergraduate creative writing exercise into a poetic response, with a meaning all its own, to one of the most famous poems of the 20th century:

…I will not climb again their lonely stairs.

But I digress. Come, I want you to meet

the woman who gave me a peach

and licked the juice as it slid down my chin,

the woman I married, waiting for us now

in the park. …

By questioning and gently chiding his conceit even as he’s developing it, Dunn saves this persona poem from faltering into the maudlin. Conscious of the motifs he’s sharing with Eliot—including the assumption of the presence of a listener, the “you” figure in the “us”—he flouts mere imitation for an act of originality under the guise of continuance, or emulation. The ending consists of a simple plea: “I’d like you to believe/I’ve learned to sing a different song.” There is no assumption of realism, of verisimilitude, here; savvy to the limits of this thought experiment, Dunn’s speaker doesn’t spout conversion, but hints toward it. The poem reads not only as an act of refutation, arguing against “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” on the surface, but as the speaker’s attempt to convince himself of the validity of his own ideas.

The result is a hard-won yet uneasy sense of assurance, a mood that permeates most of Here and Now. Just as the book’s title invokes the present moment, that moment itself is where so many of these poems live: ultimately uncertain of their fragile certainty, but certain enough to balance on the fence between possibilities. Dunn’s skill is such that he can render the most precarious of intellectual debacles with a tone that belies their complexity. Nostalgic remembrances do battle with the scientific dissection of experience in poems like “Around the Time of the Moon,” in which the 1969 landing is recalled. Even when the poems exist in obviously fictional worlds, such as in the Sisyphean allegory of “The House on the Hill,” they are acts of seeing rather than looking, of perception rather than observation. Yet they always remain several degrees away from didacticism, even when they poke at the most contentious of topics. “Shatterings,” an ode to a rebellious student, is one such poem:

…My class is called Whatever I Feel Like

Talking About. No matter what the subject,

over the years it’s been the only course

I’ve ever taught. Meanwhile, a rose explodes

on the chalkboard, three crows caw a hole

in the sky. My job is to shatter a few things.

Should I put them back together?

That there are few singularly incredible poems in this collection is an aspect outweighed by their collaborative luminosity. Dunn, a master of the type of nuance that deceives one into classifying it as insignificant on the first read and utterly crucial on the second, understands how to order his pieces, and does so seamlessly. Read apart, the poems generally consist of “Huh!” moments—the reaction of the reader that in part indicates an acknowledgment that something skillful has been achieved, some slight of hand, but perhaps not much more. Read in a linear sequence, from cover to cover (or even together in one sitting, but out of order), each poem graduates from a “Huh!” to an “Aha!” Something clever has been done, as was recognized previously—but it was not cheap or cheesy, nor was it simple. The “trick” required immense labor, and natural talent in addition to trained skill. Even greater than the trick, though, was its cover-up: held to the light of inspection, the bones of structure can be detected, but put the light down and they disappear back into the body.

With Here and Now, Dunn has realized the best thing one could have hoped, both for himself and his audience: the preservation of his status as a giant of contemporary American poetry. Dunn is here, and he is here now, with even stronger force than he possessed before. He has arrived, and to have taken the journey alongside him—and his panoply of selves—was time well spent.