“California,” publisher and author Malcolm Margolin writes in his introduction to the anthology New California Writing 2011 (Heyday, 304 pages), “is a construct of the human imagination.” California encompasses no “definable ecological or cultural area;” we are self-defining, he suggests. If we managed to evade utter disintegration for most of our history, it was thanks to heaps of luck – bountiful natural resources, good climate, driven people.

“California,” publisher and author Malcolm Margolin writes in his introduction to the anthology New California Writing 2011 (Heyday, 304 pages), “is a construct of the human imagination.” California encompasses no “definable ecological or cultural area;” we are self-defining, he suggests. If we managed to evade utter disintegration for most of our history, it was thanks to heaps of luck – bountiful natural resources, good climate, driven people.

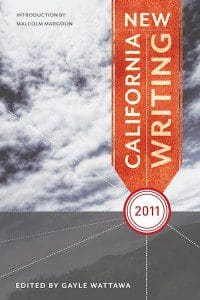

Unfortunately, around mid century it would seem our luck began to dry up. Writing in 2010-2011, the forty-four featured authors in this anthology (edited by Gayle Wattawa) greet us from the pits. The Central Valley, Mark Arax chronicles in his stunning expose of development related corruption, has become an unsustainable economic quagmire as weak local politicians repeatedly bow to almost cartoonishly Mafiaesque developers. Mojave miners must wage war against what could only be described as the anti-human labor policies of the ever-growing foreign corporate giant Rio Tinto – a David versus Goliath travesty Mike Davis compellingly describes. At least, Margolin consoles, bad times seem to produce great writing.

What Margolin means to say, of course, is that great writing has the power to reveal veiled truths – be they beautiful or ugly – and thus stands to be a force for renewed perception or social change; it is a crucial act of Californian self-definition. In this sense, New California Writing 2011’s social-issues pieces – especially the two mentioned above – are exemplary. Davis’ reportage in particular gives cause for hope despite a chillingly dystopian milieu. (Some pieces aren’t as excellent. Gray Brechin’s incensed call to stop the gutting of public education and return to a New Deal social ethos is full of good points, but they’re submerged in a bitter, generationally self-congratulating tone that undercuts his attempt to be forward-looking.)

The rest of the anthology’s writing cycles through themes of nature, family relationships and minority culture experience (among other things). While their impact may be less dramatic than some of the aforementioned pieces’, the selections are, by and large, rife with poignant social/cultural insight and first-rate storytelling. In “My Kitsch Is Their Cool,” Sandip Roy articulates an intense ambivalence toward cultural exchange, mulling over his feelings about culturally well-versed San Franciscans (the sort for whom frozen Indian cuisine has replaced the T.V. dinner) ingesting en masse Bollywood films, which he admits are ridiculous but for which he holds a deeply engrained, even protective fondness. Rebecca K. O’Connor’s tale of her relationship with a Peregrine Falcon (an excerpt from her memoir Lift) is moving. So is novelist Louis B. Jones’s “The Mere Mortal,” a successful single mother’s loving, if unsparing view of her obnoxiously radical, inspiringly idealistic college-bound daughter.

As a whole, the collection is sprawling. And with the exception of a handful of weeds, the anthology makes for a compelling mosaic of contemporary California – at times beautiful and at times inspiring, if not terribly sunny overall.

One thought on “A Sprawling if Not So Sunny State: ‘New California Writing 2011’”