Reading the late Inger Christensen’s poetry collections Light, Grass, and Letter In April (New Directions; 148 pages), as translated by Susanna Nied, is akin to stepping into a river of deceptive depth. The long-celebrated Danish poet doesn’t parade with fanfare the complexity of her work. (The first poem in Light is just six lines.) Yet progressing through these poems, a strong, invisible current pulls on the reader with gathering strength. With a plaintive tone easy to underestimate, Christensen allows her algorithmic language to work as a sort of vortex that warps one’s perception of reality.

In Nied’s crystalline translation of three of Christensen’s collections — two of which, Light and Grass, are her earliest, and all of which are appearing in English for the first time — economy and profundity share a seam. Christensen, who died in 2009, possessed a fondness for intricate frameworks in her pieces. “The structure of a work isn’t usually seen as a type of philosophy,” she is quoted as saying in the book’s introduction. “But that’s how I think of it, and I believe it’s been that way for me since my first book was published.”

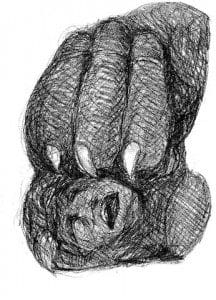

Not unfamiliar with Christensen’s work, Nied translated her 1981 book alfabet (Alphabet), a text that incorporated Fibonacci mathematical sequences. Christensen’s penchant for the interdisciplinary doesn’t stop with numbers. Her poems, according to Nied, bear the influences of Heidegger as well as French composer Olivier Messaien, an innovator of a musical approach to tonality known as serialism. Letter in April capitalizes on this concept, composed of a series of sections and subsections that contain corresponding and repeated motifs alongside the work of illustrator Johanne Foss.

Hardwired toward imagism, Christensen writes with a looping sense of relation and recurrence: snapshots and motifs show up twice, thrice, even more. Sometimes, as the patterns decoded by Nied demonstrate, this is intentional. With such verbal Rubik’s cubes, Christensen seems almost a philosopher’s poet, intrigued by the hypothetical as well as the actual. But other times her poems feel spontaneous. The known world is referred to as such for a reason — that it contains a predetermined encyclopedia of objects and coordinates — and, understanding this, Christensen mines every possible nuance from a thing while toying with the collective memory of it.

By the end of Light, what seems to be order in these poems may in fact be the opposite. Through verbal slurries of supposedly irreducible items that make sense within their lines but not, often, within any larger context, Christensen pokes and prods at the boundaries of delineation. Witness a portion of “Jellyfish,” in which an encounter with another natural entity disputes self-realization:

I note the haphazardly sectioned design

mysterious unity of eyes and sex

a listening for other systems of suns.

Are you crying again. How scattered we are.

Christensen is concerned not just with the relationship between words and things — one that might best be summoned to the American consciousness in the work and criticism of William Carlos Williams and his famous dictum, “no ideas but in things” — but the mind and the body, the self and others, the chaos of the world and the chances of obtaining even the smallest shred of immutable knowledge. In the atmosphere created by these poems, it is not just the body’s negotiation with its place in space-time that is jarring, but the body’s acknowledgment, or possibly ultimate acceptance, of itself. In these pieces, often devoid of any designated speaker or sign of life, the body can become its own virus, its own invader to be fought and rejected, as in an untitled poem in Light:

Christensen is concerned not just with the relationship between words and things — one that might best be summoned to the American consciousness in the work and criticism of William Carlos Williams and his famous dictum, “no ideas but in things” — but the mind and the body, the self and others, the chaos of the world and the chances of obtaining even the smallest shred of immutable knowledge. In the atmosphere created by these poems, it is not just the body’s negotiation with its place in space-time that is jarring, but the body’s acknowledgment, or possibly ultimate acceptance, of itself. In these pieces, often devoid of any designated speaker or sign of life, the body can become its own virus, its own invader to be fought and rejected, as in an untitled poem in Light:

Water surface

cuts itself

with ice

[…]

Beneath the skin

a heart

stands guard

In Light particularly, and also in Grass and Letter in April, Christensen rarely makes use of periods. When she does, they often show up in a piece’s last sentence. So exceptional is the occurrence of the device that one wonders if Christensen is purposefully extending the philosophical themes of her poems from the contents of language itself all the way to punctuation. This would make sense: The majority of the works in Nied’s translation are so skeletal and tight that the scope of what constitutes intention widens considerably. Periods, then, are vestiges of the same order Christensen’s delirious repetition systematically demolishes, or is intent on letting self-destruct. Taken as a whole, the poems both mirror and mimic the broken, faceted architecture of mental logic, as well as its behavior; they flip over, invert, reverse, debate, tear themselves apart.

What’s most striking about Christensen’s surrealism is that it masks itself as reality. The suite of images Christensen culls in these collections isn’t otherworldly in even a minor sense of the term. The human body and the habitat of nature provide her lexicon. Instead, the magic lies is in her methodological approach to the “real”: like carefully timed musical rondos, where elements repeat themselves without much fanfare but with certainty, the mundane continually re-invents itself by degrees until it is rendered foreign.

Christensen’s stark precision isn’t weakened when she delves into long-form or prose poems, such as those that inhabit the latter half of Grass. Instead, her kaleidoscopic complications of the real world become exponentially more intoxicating. “I do not know what it is,” she begins the third section of “Meeting.” “I cannot tell you what it is I have / no clear concept; as with words, it is no longer clear what / they are.” One of the most overall striking of Christensen’s works, “Meeting,” is saturated with a sense of grappling, a confusion and a confrontation of humanity’s place in the realm of ideas — of language itself. The seventh and last section of the poem begins and ends with the intensity and the terror of self-discovery:

With my back to my poem, to myself, to my word, I go away

from myself, from my poem, from my word, and ever far-

ther into my word, into my poem, into myself

[…]

…at the same time you and strangers

let me here at the brink of the whiteness, the unknown, write

a short message: to you, my love, neither life nor death,

but this word we use so often, in our foreign language we

have called it love.

At crucial moments such as these, Christensen rescues a potentially mechanical poem concerned only with the mathematics of language from its own obsessions. Constantly entertaining a near-insane feverishness as well as a lifelessness in her work, she allows the frustrating and ever-constant human battle with relativity of meaning — so indigenous to her poetry — its triumphs. “I think, / therefore I am part / of the labyrinth,” Christensen writes in Letter in April, bluntly summarizing the hundreds of pages of linguistic maze she and her readers have traversed.

One thought on “Ruins of the Real: Inger Christensen’s ‘Light,’ ‘Grass,’ and ‘Letter in April’”