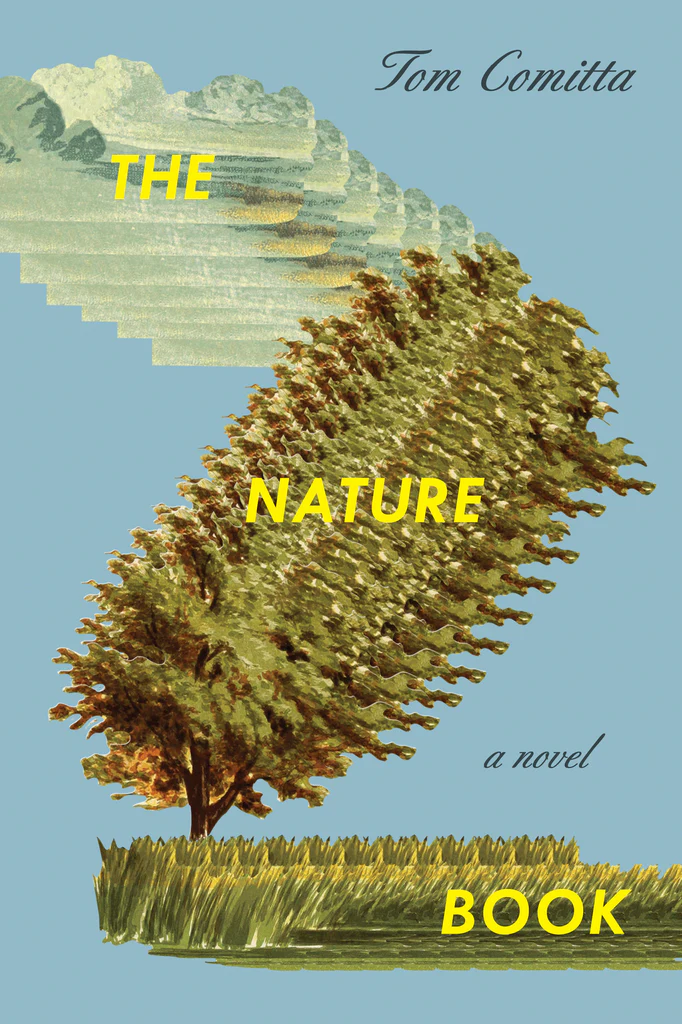

In Tom Comitta’s new work of fiction, The Nature Book (272 pages; Coffee House Press), we never encounter a human being. Taking the form of a literary “supercut” that pieces together words from over 300 novels, Comitta’s collage redirects our attention to the life force that pulses through land, water, time, and outer space. Comitta (they/them) uses ornate prose to describe how time moves across seasons to paint a fresh picture of the world and how all nonhuman life fits into it. A standard fast-paced plot is replaced with a gentle rise and fall in action that decentralizes any characters—wolves, whales, atoms traveling through atmospheric winds—and tests the reader’s patience.

Across the novel’s four sections (“I. The Four Seasons”; “II. The Deep Blue Sea”; “III. The Void”; and “IV. The Endless Summer”), the scope of the language Comitta includes is as vast as the sources they draw from and the subjects they explore. Readers first encounter a scene of spring that invokes biblical Creation before being carried into the woods, plunged under the ocean’s surface, and flown past the Earth’s atmosphere.

Comitta draws material from literary classics by the likes of Mary Shelley, Charles Dickens, and John Steinbeck, and also includes words from more contemporary, non-white authors like Zadie Smith, Amitav Ghosh, and Toni Morrison to complete The Nature Book, all without including any words of their own. The sources are impressive and offer beautiful text, but more remarkable is how Comitta weaves them together to form a cohesive narrative. To do so, they set constraints for themselves that they listed in the afterword:

A nature description can be as long as a few paragraphs or as short as “a tall tree.”

A nature description ends where a human form or human-made object begins.

A nature description may contain a reference to a human form or human-made object only if the form or object is used metaphorically.

These constraints make for an unusual narrative that cannot escape the lens of human observation and the limitations of the English language, yet excludes the human image entirely. But this does not mean the book is without engrossing conflict—its structure forces readers to invest in systems that are unfamiliar to them and that might not normally hold their attention, like this scene of a lone horse:

It seemed as if there was a fire lit, an altar burning on the prairie, a solitary flame frayed by the wind that freshened and faded.

The horse could not see it well enough to know. He continued on across the grass, looking confused. Then he stopped, staring. A mile away a troop of figures passed between him and the light. Then again. Wolves perhaps.

Although Comitta’s own words aren’t in The Nature Book, the author’s omniscient narration takes on a style of its own and becomes as captivating and comforting as the voice of an elder guiding a child through a fairy tale. The Nature Book succeeds by simultaneously upholding nature and respecting centuries of human observation of it. Comitta’s meticulous dissection and reconstruction of the source materials immerse us anew in the wonders of our world.