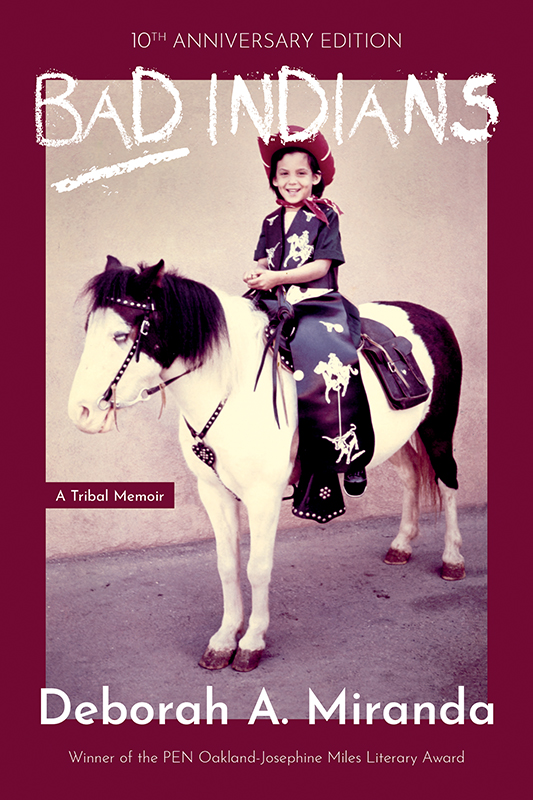

Deborah A. Miranda’s multi-genre memoir, Bad Indians, was first published by Heyday Books in 2013 to great critical acclaim. Miranda uses found text, poetry, fiction, and personal essay to create a gorgeous and devastating reflection on not only her childhood, but on California Indians as a community since the establishment of the mission system in 1776. With darkly playful subversiveness, Miranda frames the book as her belated Fourth-Grade Mission Project: an assignment that all California fourth-graders are required to do as part of their sanitized mission history unit. This ground-breaking book won the 2015 PEN Oakland–Josephine Miles Literary Award as well as the 2014 Independent Publisher Book Award Gold Medal for Autobiography/Memoir, and was nominated for the 2014 William Saroyan International Prize for Writing.

This year, the tenth anniversary edition of Bad Indians was released by Heyday, offering a beautiful hardbound edition with over fifty pages of new material. A tremendous admirer of both Deborah Miranda’s poetry and Bad Indians, I was delighted to talk with Deborah about her memoir, her practice as a writer and teacher, and the new pieces that made their way into the latest edition. Miranda is an enrolled member of the Ohlone-Costanoan Esselen Nation of the Greater Monterey Bay Area in California; she lives in Eugene, Oregon, with her wife, writer Margo Solod, and a variety of rescue dogs. She spoke to ZYZZYVA via Zoom. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

ZYZZYVA: You mention in your introduction to the new edition that after the book’s initial release in 2013, you kept writing pieces you describe as clearly belonging within the covers of Bad Indians. Do you feel like you have an iterative practice around this memoir?

DEBORAH A. MIRANDA: It has turned into that. I’m not sure that I started out that way, but the stories just keep coming. No matter how much research I do, I’ll never reach the bottom. I think that’s a testament to the number of voices that have been silenced or erased, and are waiting in the archives for the right ear to come along. I was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time and to have had a practice for many years as a poet, so I had an ear for the kinds of images that I was running across. I’m mixing my metaphors there, but there are images that I come across and I can’t forget. That opens the door for me into a story that hasn’t been told or hasn’t been told from an Indigenous perspective.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be done with either Bad Indians or with the project of recovering voices from the colonizer’s archive and allowing Indigenous voices to tell their story. When I finished this book, I realized this is all the material I ever need for the rest of my life. Also, in traditional storytelling there were stories, but they continued to evolve and develop with the geography and changes in climate and changes in food sources. There was a central core to those stories, but they never really became static.

I went into the archive thinking, “Oh, I won’t find anything.” I came out realizing I’m not going to live long enough to tell all these stories.

Z: There’s so much careful repetition central to Bad Indians: the facts about your family history, such as your father’s incarceration, your mother’s breakdown and disappearance. We hear these multiple times yet from different perspectives. What is the role of repetition in both your life and your work?

DM: I’m thinking of the stories in this book that are really personal. They’re almost a kind of map, a geography of my childhood: where I came from and how I became who I am. In that map, there are places that I need to revisit from different angles. It’s like taking different doorways into the same event. Because I’m a different person every time I remember it!

The story about my mother’s disappearance and my father’s incarceration is a story I return to over and over again because I’m still trying to figure out how that changed the world for me. That story keeps getting larger and larger. I just returned from a visit to California where I was able to visit my Aunt Sally (of the Pat & Sally who took me in for a year), and every time I visit her I get new stories. A story I had never heard and kind of blew my mind was that my mom had come back many times asking for me. My aunt had sent me to another room and told her, “You can’t have her back until you go to rehab.” The guts! She didn’t have her husband do this. She told my mom in no uncertain terms: “Yes, we have her, no, you can’t see her, and no, I’m not giving her back to you until you can get yourself together and take care of her.” I never knew that story.

So there’s always more to the story, which means I need to go back and rethink things and reprocess. The repetition has a lot to do with that. But it’s never the same repetition, I’m revisiting the same place but in a different way.

Z: Do you ever make visual maps as part of your writing?

DM: I do! I doodle a lot. If I get stuck, I pull out a blank page and start drawing a map or a timeline, or a timeline that turns into a map. Typically, when I’m stuck with language, I need to turn to something visual. Or I turn to a poem. Those two things really help me corral the words that I need and find a way into the story that I’m trying to tell.

Z: I love that. It makes me think of the work of Lynda Barry.

DM: Oh, I love Lynda Barry! You know, I may have learned that from her, because I’ve taught a lot of her books. I love her book Syllabus. I’ve used a lot of that in my creative writing classes. And What It Is, the narrative of her becoming an artist and writer, oh my gosh.

Z: When I first read this memoir, it struck me as an incredible piece of self-love as well as generosity. As a teacher as well as a poet, do you see those things as fueling your work?

DM: Well, as a child who was abandoned, I have always had real issues with feeling lovable. In some ways, that is the basis of all my writing. Who am I? Am I lovable? What’s my purpose?

I went into writing Bad Indians with no doubt in my mind that it was for California Indians, specifically for my two tribes, the Esselen and the Chumash. I could see that the community at large was kind of a mirror of my personal experience. Many of the same issues and what society calls “dysfunction” were the immediate result of intergenerational trauma. That showed up in my life pretty vividly with my father, but I could see that it was everywhere for other California Indians. Part of the problem was we didn’t have our own narrative. Somebody else was always telling our story and they never told it from a loving perspective. I think the word “love” is a good idea. As I buried myself in this research and got to know these ancestors, I loved them. I felt very attached to them. I wanted them to be heard! It was really an act of love to slog through all that trauma and all the ugliness that they endured in order to find those stories that could say: we were here, we were human, we were amazing. We were survivors.

You know, one thing that came out at the end of the book and just rocked me on my heels — I did not realize that one of the many threads in this book is my dad and me. It wasn’t until I got to the end that I realized I needed to resolve that relationship in some way. It’s very hard to understand how you can love someone so intensely and at the same time be so angry with them and hate them, literally hate them. Then I found out some of the things that went on in some of the missions and began to understand how historical trauma is exponential: five or six or seven generations, each one never getting a chance to heal or catch its breath. That increases the trauma tremendously. And you lose track of the original trauma and you start to think, “We’re just really bad! We’re just incapable of having families! We can’t have marriages! We drink a lot, we are diabetic and overweight.” You start believing the colonizer’s stories about you because you don’t know how you came to be in this place.

It seems to me that through loving my ancestors I found a way to love myself.

Z: That contextual understanding of your father is very present in “Tuolumne.” Both that piece and “Transplant” are so lyrical and attached to land. Where did those pieces originate for you?

DM: “Tuolumne” is one of the new pieces in the tenth anniversary edition and so is “Transplant.” It struck me at some point as I was writing that I was so lucky to end up on that piece of land in Kent, Washington, for ten years. For “Transplant,” I really wanted to honor the land for what it had given me and how it had mothered me. In my family, that piece of land is just legendary. We always called it The Property. “We lived on The Property in Kent.”

I’ve taken to Google Earth and looked it up. At first, I was very hesitant because even while we were living there, this huge housing development was encroaching closer and closer, and I hadn’t gone back since maybe I was 18 or 19. I was worried about what had become of it, but strangely enough there’s still a piece of it there. The creek has been put underground but there’s still a remnant of the place where I experienced so much healing. So I wrote a piece to try to capture that, to save it, since I can’t save the land in this particular case. I can save the memory and the knowledge of what land can do for a wounded child—and write a story that honors it.

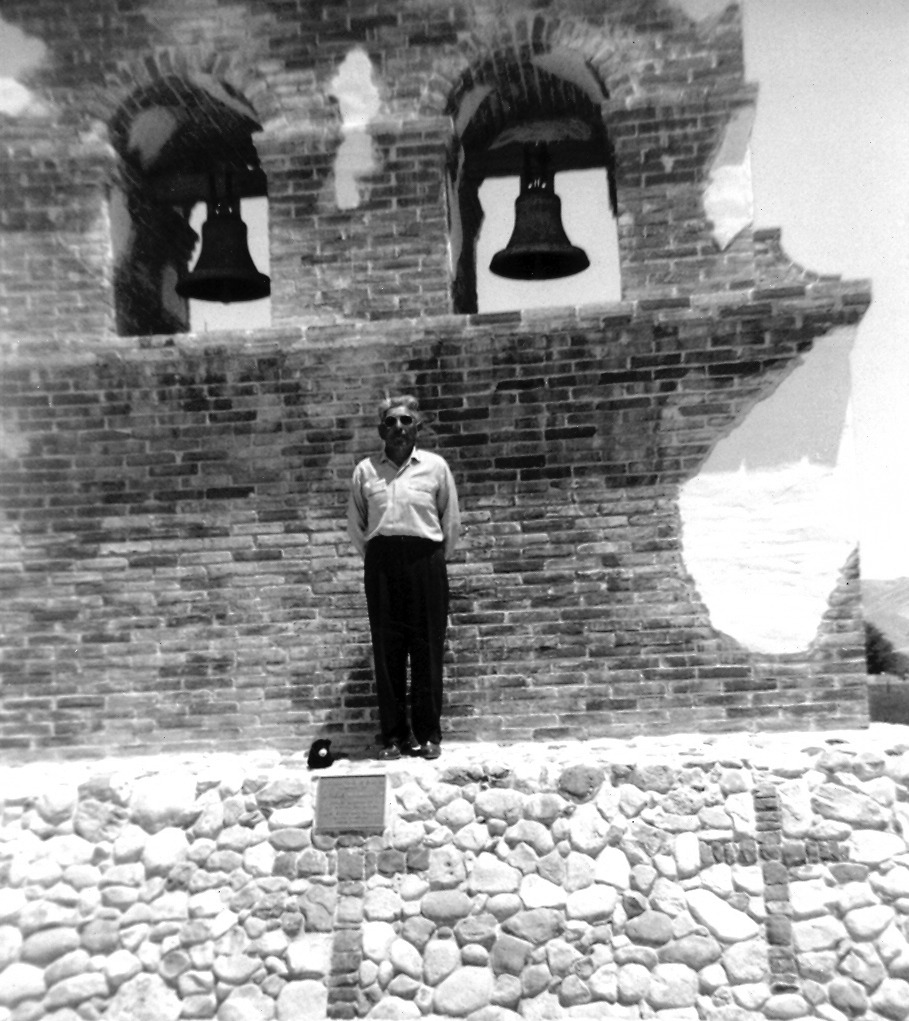

Z: Speaking of giving voice to place, I was so delighted by the series of poems in which you give voice to the missions themselves. They’re so darkly funny and snarky. You write in the introduction that they originated on a train trip you took to visit all the missions, but how did that tone emerge for you?

DM: Gosh. You know, it was similar to the tone that I took with my Mission Glossary: a little bit sarcastic, a little in-your-face. I would go to a mission for a few days, stay somewhere close by — in one case I stayed in the mission because they have a retreat center there, that was really weird!—and I would just go sit in various places. I took a lot of photographs and I tried to listen for a voice from the mission. Whatever I heard, I started writing about. The poems are interviews, really, with the missions. I was trying to see what would come out. I have to say, I am not in as much control of these things as people imagine! Sometimes something else steps in; oftentimes, I’d say. It’s when I try to control things that they go miserably wrong. So, I let the missions have a free hand and say what they wanted to say. I was really nervous about that first one about San Diego, the zombies—wanting to die, wanting to be burned down. And ten years later, a mission does burn down! Oh no!

Z: I loved that one, “San Zombie de los Muertos Vivientes,” and the idea that a place might wish to be destroyed. Like some of your other pieces, such as “Mestiza Nation” and “Coyote Takes a Trip,” that poem is lightly speculative. Do you have a relationship with the word “speculative” as applied to your work?

DM: I think it’s a good term. I certainly like it better than a lot of the alternatives. Science fiction or fantasy, those all have connotations. But it also makes me think of the term magical realism, and how a lot of Native people and Latinx people have pushed back against that term and said, “This is our reality, it’s not magically real, it’s our reality!” I feel like that about these stories. Speculative is a good way in, but really, they’re a glimpse of the world through an Indigenous lens. For a lot of Native people, Coyote is very present. That story began when I was on a bus to Venice Beach! A raggedy beach guy got on the bus and tried to get up and accidentally dropped his pants in front of these three women. And I thought to myself, “Wow, that was a real Coyote move.” I went right onto the beach and wrote down part of that story. So, it’s how you look at the world sometimes, what you’re open to seeing. Coyote is everywhere. He really is. Or she really is. They really are! Everywhere. Sometimes you catch a glimpse.

Z: Coyote makes me think of the loving queerness in Bad Indians and your poetry—we could have a whole other conversation about your poetry!—and I wondered if you might talk about that a little more. You’re vulnerable about other areas of your life in Bad Indians, but in it you just hint at your queerness and your long lineage of queer ancestry. Was that an active choice?

DM: That’s a really interesting question. I was not consciously trying to keep my queerness out of Bad Indians. I was so focused on connecting things to missionization and I didn’t see a clear connection for my personal story of queerness to that material. Which is to say I haven’t seen it yet! Also, I feel like I told my story in my book of poetry The Zen of La Llorona. Unfortunately, that book is very hard to find. I’m going to have to do something about that! The thing is, in the long story “Silver” that appears toward the end of the book, I gesture toward falling in love with a woman. That is a story I struggle with, because at the time I wrote Bad Indians that person was still alive and I didn’t want to reveal too much. I was struggling to respect her boundaries and other people’s boundaries. I also didn’t want that to take over the narrative. And, too, I don’t want to write negatively about the father of my children. So, I cut out a lot of that material, that’s maybe for another day another time. When you put something in print, it just becomes larger than life a lot of times.

Z: That’s a theme I’ve heard about the experience of writing a memoir. Several memoirists have shared that people often feel like they know you. Have you experienced that in positive or negative ways?

DM: Yes, that happens a lot. It takes a while to get used to, because people are speaking to you as if you are their dear friend. They want to share a lot with you, but usually not under very intimate circumstances. It’s hard to really listen to someone else’s story when you’re a guest at a university or at a bookstore. That’s probably the hardest part for me. I really do want to hear their story. I really do want to know what came up for them when they were reading my story. If there’s a negative at all, that’s it. It’s that there’s never enough time, there’s not enough me!

But I also tell myself, they’re happy to be telling me things, to meet me, to feel like they know me, and maybe that’s enough.

Z: Since Bad Indians was first published, there’s been both so much more awareness of Indigenous peoples and more appropriation. People protested in solidarity with Standing Rock, but also people use white sage to smudge spaces when that is not their traditional practice. How much has that shift played into your thinking around reissuing the book?

DM: The thing is, Native Americans have been dealing with appropriation almost since Day One. We are entirely accustomed to it. I would say a lot of us just expect it. But there are other ways to respond to it now. One of the Indigenous businesses that I buy from, Eighth Generation, has this great sticker that says: Inspired Natives®, not “Native-inspired.” It’s a way of saying be mindful that there are good Indigenous businesses to purchase from rather than running to the internet and finding a random sage dealer! So I would say we’re pretty practiced in dealing with appropriation. We’re not immune but—we’re hardened to it. It’s nothing new.

But now we have more ways to utilize media in order to put our own voices forward. For example, when Urban Outfitters had some Navajo print underwear. People were able to call that out and create a situation in which it was dealt with. We’re not as vulnerable as we used to be.

But in terms of what’s happened in the last ten years since Bad Indians was published, you’re right. Just watching Reservation Dogs, I’m in heaven! I’m delighting at every possible angle and I love all the in-jokes. Seeing the Poet Laureate talk about someone needing to go clean up the shitter! So awesome. Yeah, we’re having a moment. I hope it continues.

And California Indians have been part of that. We had a lot further to come than other tribes because people didn’t realize there were still Indians in California. We needed to make up a lot of ground. I see all the upcoming writers and upcoming scholars and I’m just thrilled. Actors! Writers! Musicians! It’s amazing. And here I have to put a plug in for my sister Louise’s play called IYA: The Ex’celen Remember, which has had several play readings recently. It’s a beautiful story, it tells my sister’s story of losing a daughter to leukemia and the ancestry involved in that.

Z: This is reminiscent of the way you write in the new edition about the fight against the canonization of Junipero Serra. Even though you weren’t successful in stopping the canonization you were successful in discovering new tools and community and history.

DM: It was a real learning experience for California Indians. It woke us up in a big way. I’m still grateful for that experience even though we didn’t succeed. Thirty years ago, people were fighting against the canonization but we weren’t this organized. Now, more people know the story.

Z: I know that you recently retired. Are you able to work full time at your creative practice now?

DM: I will be, once I’ve completed the next stage of my move from Virginia. I’m excited that you liked the mission interviews. In terms of future projects, that’s a dream I have. There’s a big coffee table book called Mission Memoirs, it’s hardback, it’s got these glossy pages, fancy typography. I want to do a take-off on that with those poems and with my pictures and with interviews with California missions. That’s a dream, you know? But sometimes you have to put a little of a dream out in the world to make it come true!

Maura Krause is a writer and Barrymore-nominated theatrical director, currently pursuing their MFA in Writing at California College for the Arts. Maura’s writing explores gender and emotion intertwined with the natural world. They were the Artistic Director of playwrights’ collective Orbiter 3, and most recently directed the East Coast premiere of Anna Moench’s Man of God.