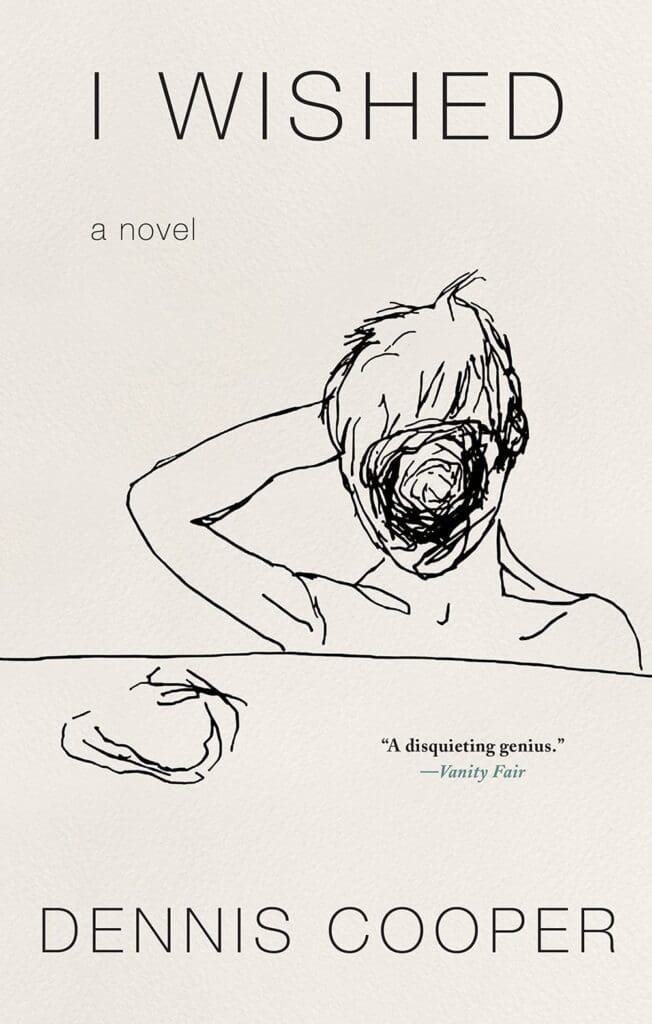

George Miles. To the average reader, it’s not a name that necessarily conjures associations; but for followers of underground literary icon Dennis Cooper, it’s a name that has loomed large since the publication of Cooper’s first novel, Closer, in 1989. That book marked the beginning of Cooper’s most enduring body of a work, a five-novel series collectively known as the George Miles Cycle. The novels form a loosely connected narrative that, by Cooper’s own admission, represent his attempts to process his relationship with Miles, an enigmatic young man suffering from mental illness and a general difficulty at articulating himself. Unbeknown to Cooper until many years later, Miles committed suicide before Closer ever saw release—and yet the author’s work continues: Cooper’s first publication in ten years, I Wished (127 pages; Soho Press), blurs the line between fiction and memoir as Cooper tackles his love for George Miles in the most plainly naked form yet.

The prose reads as unmistakably Cooper—as minimalist and unadorned as an anatomy-class skeleton—but the author seems to have turned off his usual fog machines, no longer obscuring his obsessions with the usual twisted funhouse of drug-addled teenage characters and the middle-aged sadists and pornographers determined to reduce them to pulp. “Reality is so controlling, and I’ve never tried to stay there when I write before,” states Cooper. “This is the first time in my life that someone in the world has made me want to undermine my fiction when it frees me to forget the world…” Here is only a boy named George, and his friend Dennis, who as an adult can’t seem to reckon with the central contradiction of their lives: that George has served as the basis for most of Cooper’s lifelong artistic pursuits and yet left seemingly no mark on most everyone else in his life.

This inequality spurred I Wished into being, impressing upon Cooper a particular task: to use every faculty and skill he’s developed as a writer to convince us—the reader—that Miles mattered, was worth remembering, and was indeed worthy of love (no matter his failings as a son, a brother, or friend). Cooper admits this is a losing game: what could be less compelling than reading about the depths of a stranger’s passion—a kind of secondhand experience of love? “It’s a lot to ask since what I feel is not something I can capture, other than to say, Look, I’m another writer who is obviously in love and who has lost my way linguistically,” Cooper writes. “How do I make you care, since no one cares that much about another’s love.” And yet Cooper feels he must persist.

The book unfolds through a series of short sections that range from autofiction in nature to more abstract essays. The essays touch on topics as varied as the 1968 film adaptation of Carson McCullers’s The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, Santa Claus (“His kindness makes him lonelier and less real, if anything…He’s just the circumstance that causes everyone to get some things they love once annually”), and the Roden Crater in northern Arizona, yet all filter their subject matter through the lens of Dennis and George’s friendship. Toward the end of this slim book, Cooper explores some of the most compelling aspects of his own life, including the incident in which a friend’s careless swing of an axe split open Cooper’s skull and nearly killed him as a boy. (“When I woke back up at some convenient point, my head was firing blood in all directions so I struggled to my feet and ran screaming up the driveway.”) Later, he projects himself into George’s house the night in which a 30-year-old Miles committed suicide while listening to Nick Drake.

Given that the book heavily relies on one’s familiarity with the George Miles Cycle, it perhaps goes without saying that I Wished is difficult to recommend for those new to Cooper’s work. Due to the graphic nature of much of his past writing, he’s never been the most accessible of artists, but directing your first book in a decade at only your most devote readers is the kind of bold move you can only get away with if you have an established following (and a publisher willing to take that risk).

It’s telling that the George Miles Cycle seemed to grow in complexity with each installment, culminating in the sprawling Los Angeles narrative of 1998’s Guide, only for Cooper to conclude the series with the shortest and sparsest book of the entire series, 2001’s Period (128 pages), in which it feels as though the author ends his project by simply vanishing from sight. Twenty years later, I Wished might be what remains onstage after the scenery has been wheeled away and the house lights have been turned on. It is a writer laying bare his inner longing in spartan fashion. These days, our culture can look upon the relationship between an artist and their muse with some level of suspicion, often questioning the creator’s motivations. But it must be said few artists working today have devoted themselves so intensely to preserving a subject’s memory—serving as eloquent witness to a life that was otherwise overlooked and almost certainly misunderstood. And so, Cooper gives us I Wished—his own attempt to understand. Like much in life, we sense it’s an ongoing process.