In his new book of poetry, Pilgrim Bell (Graywolf Press; 80 Pages), Kaveh Akbar plays with the spiritual, familial, and corporeal. The poems meditate on the places of our origins; the land from which we came, the people through which we arrived, and the languages we spoke among and after those places and people.

Kaveh is the winner of a 2017 and 2018 Pushcart Prize and is the Poetry Editor at The Nation. ZYZZYVA spoke to Kaveh, whose poems appeared in Issue 107, to discuss the book, God, and miracles.

ZYZZYVA: The first and the second to last poem of every section in the collection is called Pilgrim Bell. What’s the intention behind that?

KAVEH AKBAR: What interests me about bells are the repetition of the ringing, the fact that they are a theological and spiritual technology but require the heft of a human body to move. You have to use the human body to pull the rope to ring. That was really interesting to me, and I throughout the book there are incidences of repetitions and echoes. What you’re pointing to with the shape of those is an instance, or an iteration.

Z: Many of your poems seem to be in a kind of conversation with God or about Biblical texts and teachings. Considering that you finished the book during the pandemic, did you ever find yourself talking to God? Are the poems a way of speaking and communing with God?

KA: That’s a big question. When I say the word God [Kaveh gesticulates arms upward] I mean all of it, which is to say I’m as confused as anyone about what I mean. I identify as a Muslim, though there are plenty of Muslims in the world who would not approve of me being one. The common formulation is that prayer is a way of speaking to God and meditation is a way of listening. For me, poetry is often both. Its role is sometimes purely speaking to, its role is sometimes purely listening for, and quite often it’s a mixture of both of those things in the reading and composition of the poetry.

If I could say in the language that we’re using to talk to each other now, what I mean when I say the word God, I would just say it. But I can’t. I don’t think that the technology of the English language can accommodate that. I think it’s only through the warping of the medium that happens in interesting lyric poetry that one can approach something like clarity when talking about things as massive as God or love or fear of death or loneliness or any of these things.

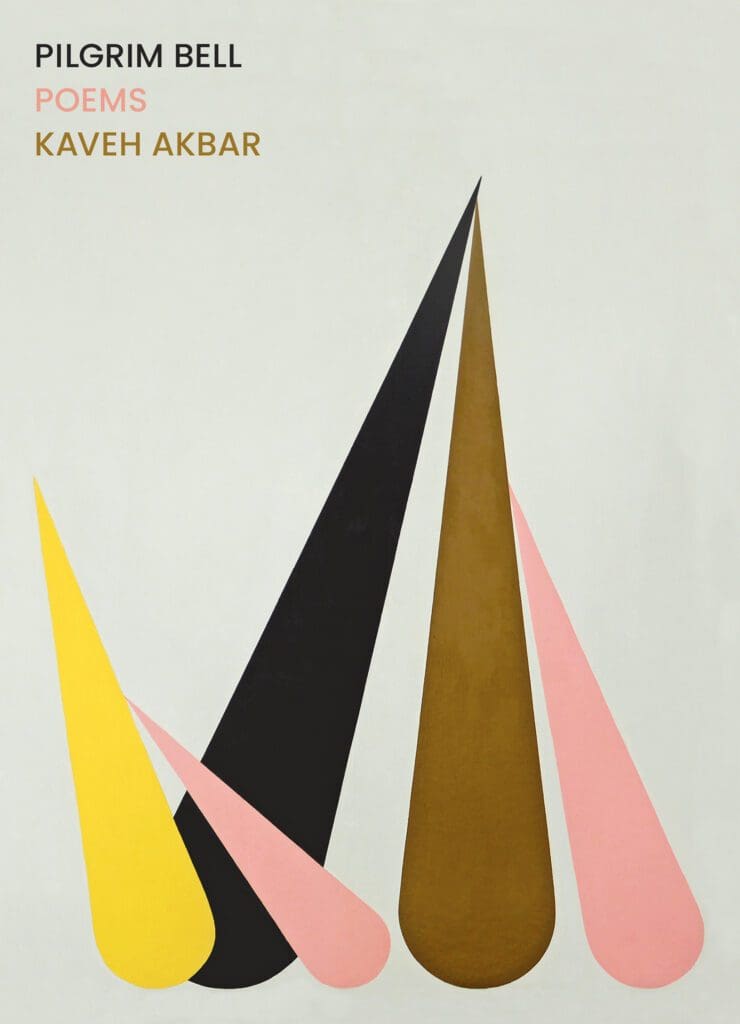

Z: Can you tell me about the cover art?

KA: It was done by a friend, the brilliant painter Hannah Bagshaw. I love this piece. I sent her the manuscript for this book and she repainted a version of a similar painting specifically for this book. Every time I look at the cover it’s like I just ran eight miles and then took a cold shower and drank a triple espresso. It just gets me so wired. I’m not particularly interested in flattening it to a figurative meaning, but sometimes I’ll look at it and I’ll think, oh, that’s like the clapper of a bell or dervishes whirling, but there’s just so much energy and dynamism and also chastity. I think that it’s such a compelling thing, to have a piece of art feel both vital and energetic and dynamic but also chaste, and she really accomplishes it.

Z: You offer multiple poems about parents, existing in different bodies and embodying different genders. How are you thinking of your parents or ancestors as parts of yourself?

KA: My mother’s family was off-the-boat German and then, obviously, I’m Iranian; I was born in Tehran. My dad’s family, all the way forever back, is Iranian. I haven’t lived in Iran since I was two and half, and never will again in this lifetime. I have visited Germany, but I don’t know anything about that side of my family after my mom’s generation.

When I was young, my only conception for God was my parents. God was the absolute power and I lived in a house with a very, very powerful father who was also very mysterious and came from a part of the world that was mysterious and unknown to me. Because I’ve lived in America since I was three, my dad and I were learning this new world together. That amplified the ways in which he was magical and mysterious and all-powerful to me. I mean, I literally thought that his umbrella controlled the rain. When he grabbed his umbrella and we opened the door, it was raining. So, I was like, oh wow, when he grabs the umbrella it makes it rain, you know. So much about language and power and conceptions of the Divine and the ability to apprehend some facet of divinity in my periphery and then, understand myself—my parents are a way for me to have a model of that understanding.

Z: How does time show up in your poems?

KA: I’m really into Jorge Luis Borges, and he talks about something to the effect of: Toni Morrison influenced Cervantes. Not literally or chronologically, but if you read The Bluest Eye before you read Don Quixote, then your reading of Don Quixote will be indelibly inflected by Toni Morrison; so, Toni Morrison influenced Cervantes. That temporal relationship is something that really fascinates me.

Everything I’ve learned has come all out of order, in so many different ways. From being a low bottom addict, alcoholic, and having to learn what one learns in that stage, to getting sober and teaching myself how to eat like an adult. I mean, I had just been drinking my calories or not consuming calories at all for years. I had to learn how to eat, how to feel hunger, and how to sleep. Then there are the subtler gradations, like learning how to experience happiness to learning sorrow in a way that wasn’t just bone-crushing emotion. A lot of my learning happened out of order and I think that it has created, in my experience of living now, a lot of really weird and interesting frictions.

The stuff that I’m really interested in and want to talk about is the same stuff that’s been written about for centuries. For instance, Enheduanna is the earliest attributable author in literature and she was writing in 2300 B.C.E. It’s the same shit that the Bhagavad Gita, Gilgamesh, or the death of Enkidu is about. The more I read the more I realize how absolutely utterly precedented I am. And there’s a lot of comfort in knowing that the earliest attributable author in all of human literature was writing about being a refugee in exile and loneliness and confusion and God. In the intervening forty-three centuries, all of these titans of thinking have passed between us and we still aren’t really any closer to understanding any of it. There’s something about that that’s really soothing to me—it lowers the stakes. I know I’m not going to figure it out. I know there’s not going to be a day where I’m like, “Oh shit, that’s what God is.” Or, “That’s what desire or death is.” All these minds many orders of magnitude greater than mine haven’t been able to figure it out in forty-three centuries, so I have no delusions about being able to come to any certainties with this, which is really absolving. It’s freeing.

Z: One question I had was about the poem called “An Oversight.” The poem reads, “They say it’s not faith if you can hold it in your hands.” I want to contrast this assertion with the fact that you can hold a poem in your hands, and I think that poetry is a kind of faith. Who is the “they”? What is faith?

KA: I think this goes back to the idea of the old, ancient Abrahamic cry of, “If God would just show themselves to me, then I devote my life to him.” Or, “If he would perform a miracle in front of me on my asking that was undeniably his doing then it would be nothing for me to throw it all away and devote my life to joyful service of him.” But the theological reason people give for why that can’t happen is that then it wouldn’t be faith anymore. That’s what that line is taking issue with.

I mean, I have never experienced the sort of “burning bush” instance that the word “miracle” seems reserved for. But I’ve seen photosynthesis happen. I’ve seen light from a star get turned into sugar. I’ve seen my sister-in-law create life inside of her. I know the science behind those things, but naming magic doesn’t make it not magic. Just because we call light from a star traveling 93 million miles to Earth and alchemizing into glucose that has weight and is the bedrock upon which all organic life in our galaxy is built—just because we call that photosynthesis doesn’t mean it’s not also magic.

It’s like what we’re talking about right now: there are these shapes on a page, right? I put them in a certain order and it makes you laugh and I put them in a different order and it makes you cry, and it’s just a bunch of ink yet it provokes these biological responses within you. It makes your lacrimal glands contract and your diaphragm convulse. It’s just a bunch of shapes on a page, it doesn’t mean anything.

Z: You mention Keats in the final poem, “The Palace.” What’s his significance to you?

KA: F. Scott Fitzgerald said that after you read Keats for a while everything else just sounds like humming and whistling. He wrote “Ode to a Nightingale,” he wrote “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” I mentioned Borges earlier—he never actually heard a nightingale in his whole life, they just didn’t have nightingales in Argentina. But Borges said Keats heard it for everyone everywhere. Keats was a baby, you know—he wrote that when he was twenty-three or twenty-four; it’s absurd that he was able to do what he did with language.

You mentioned reading Rilke earlier, and he’s a poet where you feel the conversation in between him and the other world. That partition is thinner for him than it is for us mortals. Keats is like that: you just feel like he had one foot on the other side already. I was in Rome not long ago and I went to the house where he died and I visited his grave and his gravestone reads: Here lies One\ Whose Name was writ in Water. In other words: your life will just be forgotten. His name isn’t even on his own gravestone.