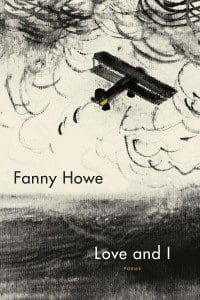

Fanny Howe prefers to be alone—perhaps that’s what makes her such a perceptive poet. In her latest collection, Love and I (80 pages; Graywolf Press), the fruits of Howe’s solitude are on full display. Howe is introspective, curious, and content when she is by herself. Many of the poems in Love and I celebrate the comforts of being alone:

Fanny Howe prefers to be alone—perhaps that’s what makes her such a perceptive poet. In her latest collection, Love and I (80 pages; Graywolf Press), the fruits of Howe’s solitude are on full display. Howe is introspective, curious, and content when she is by herself. Many of the poems in Love and I celebrate the comforts of being alone:

I’ll sit at the window

Where it’s safe to say no.

Won’t go out, won’t work

For a living, will study the clouds

Becoming snow.

That’s not to say Howe doesn’t grapple with the aches of loneliness as well: “Someone help find me an animal,” she implores, “Who will rescue me from / Being solitary.” When there’s no one with whom she can share her life, she asks, “Who will believe what I do?” The answer: no one—the only “proof that you lived is that you kept notebooks.” These sorts of autobiographical asides—brief flashes when Howe transforms herself from spectator to subject, and reveals herself to us—make for some of the collection’s most compelling moments.

In her poems, Howe paints vivid scenes and hones in on unexpected details, the kind that only catch the eye of the lonely. A keen observer and frequent traveler (she does most of her writing in transit), Howe’s gaze is wandering but sharp. She notices the child who “licked up the mist on the windowpane,” and the plane passenger who “clutched his head like an infant.” She conjures images of small, everyday beauty: “bridal curls,” “poppy seed cake,” “a grove of elms.” And for Howe, “the tinier the beauty the better.”

With a title like Love and I, one might expect the collection to be an excavation of romantic histories or an interrogation of the act of loving itself. But Howe throws her poetic net far beyond love, prodding at questions of memory and movement, of the body and nature and grief. We spend time both inside the poet’s head and within her well-crafted scenes, leisurely bouncing between introspection and dialogue, opinion and observation.

Fascinatingly, the collection’s most persistent motif is not love but children. They appear in poem after poem, playing, growing, and taking in the world. Children are everywhere: there’s one sleeping, another standing on her head. Howe finds their innocence remarkable, and she writes about them protectively, determined to safeguard their senses of wonder. “Children need a rest,” Howe writes, “their minds are swimming in junk / and fists.” And again: “Children need sugar. / Especially in danger.”

It’s hardly surprising that children are one of the governing structural elements of Love and I. In an interview with Jacket Magazine, Howe shared, “It’s very essential to me, the relationship I feel towards the future of young people, children in particular.” Unpacking this motif, on the other hand, is a more challenging endeavor. The recurrence of children inevitably incites nostalgic yearning, a desire for the ease and infallibility of early youth. But Howe’s connection to children runs deeper than that: in her poetry, Howe casts a maternal gaze, shaped by her own experience as a mother. That said, I can’t help but wonder if Howe, who retains a child-like sense of wonder and creativity, also sees children as peers, better suited to understanding her than adults. After all, she once told the Paris Review that if she “had to do it all over again,” she’d “like to be a wandering monk with some children traveling in my company.”

When Howe does turn her focus to the notion of love and its many permutations, the results are enthralling. She speaks bluntly about the pains of attachment, abandoning lush imagery to get right to the heart of things. “Is love one-way?” she asks. “Almost always.” As Howe has grown older, she finds “Love stood at a distance.” In the standout poem of the collection, “Destinations,” Howe mourns a lost relationship, writing simply, “On a side street (on my sheets) / one I love passed / as a shadow.”

One of Love and I’s most ambitious poems is “Turbulence,” a vast multi-pager that takes place on a plane ride and explores loneliness, faith, and death. A passenger, Howe notes the rain on the windows, the trembling wings, and the clouds below; wonders about the other travelers around her; and allows her mind to wander, as it inevitably does. Ultimately, she extends a comforting invitation to surrender, directed at both her fellow passengers and us, her readers—to unburden ourselves as best we can as we trudge through life:

Give up your wires, plugs, laptop, pills, water, cellphone,

Passport, ticket and shoes.

Give up your water, your wine, your songs and stories.

Put your arms up, your feet down flat and face ahead.You have not reached the end yet.

Love and I is a meander through a singular mind, a mind that observes more sharply than many of us could ever hope to—or might want to. Howe, who at 78 years old has penned more than thirty works of poetry and prose, has little to prove to us now. Her approach may not always be accessible, but Howe’s inquisitiveness, generosity, and care are easy to appreciate and impossible to resist.

Thanks for this great review. I needed a primer before diving into Howe’s poetry!