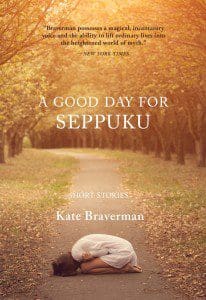

Fiction writer and poet Kate Braverman began her acclaimed career with 1979’s Lithium for Medea, a bildungsroman about a young woman struggling with cocaine addiction and a trying relationship with her family. Since that time, Braverman has collected numerous accolades, including Best American Short Story and O. Henry awards, a Graywolf Press nonfiction prize, and being named a San Francisco Public Library Laureate. Four decades into her career, she shows no signs of slowing down her creative output, and returns with her latest story collection, A Good Day For Seppuku (192 pages; City Lights Books). Here Braverman depicts characters in complex relationships that seem all too real: estranged daughters, young adults forced to choose between their parents, toxic friendships, and more. These are complicated people who bring to mind poet William Shenstone’s observation that “A liar begins with making falsehood appear like the truth, and ends with making truth itself appear like falsehood.”

Fiction writer and poet Kate Braverman began her acclaimed career with 1979’s Lithium for Medea, a bildungsroman about a young woman struggling with cocaine addiction and a trying relationship with her family. Since that time, Braverman has collected numerous accolades, including Best American Short Story and O. Henry awards, a Graywolf Press nonfiction prize, and being named a San Francisco Public Library Laureate. Four decades into her career, she shows no signs of slowing down her creative output, and returns with her latest story collection, A Good Day For Seppuku (192 pages; City Lights Books). Here Braverman depicts characters in complex relationships that seem all too real: estranged daughters, young adults forced to choose between their parents, toxic friendships, and more. These are complicated people who bring to mind poet William Shenstone’s observation that “A liar begins with making falsehood appear like the truth, and ends with making truth itself appear like falsehood.”

Though the collection’s scenarios could be dismissed as familiar tropes, Braverman brings sagacious insight to them. Her mind, a fecund breeding ground of creativity, can take a cliche such as “a wife leaves her husband” and spin it, often with a clever turn of phrase, into something like a short masterpiece. For example, in “O’Hare,” in which a 13-year-old girl must choose between living with her mother and her record-producing boyfriend in Beverly Hills, or her father in the rural Allegany Hills, she describes how her young protagonist finds herself most at home between the two places, at the Chicago airport: “I feel like I’m back in O’Hare where seasons do not exist and all rules are suspended…I press the pause button on my life and everything stops.”

Moving through the eight stories in the book, one is greatly impressed by Braverman’s ability to recontextualize themes of estrangement, substance abuse, and fractured familial relationships through her unique prose style. Page after page of the collection is filled with lyrical imagery that veers toward the cinematic, such as in this evocative opening paragraph from “Women of the Ports”:

They meet at irregular intervals at Fisherman’s Wharf. This is the neutral zone, the landscape of perpetual, unmolested childhood where the carousel spins in its predictable orbit, and the original primitive neon alphabet does not deviate. Some hieroglyphics are permanent and intelligible in all hemispheres and dialects. No translation is necessary. The carousel doesn’t require calculus, rehab or absolution. No complications with immigration or the IRS. Just buy a token.

Elsewhere, in “In Feeding in a Famine,” she uses vivid symbolism to describe an alienated young woman’s visit to her family farm: “Outside is thunder like a plane straining at a blue edge too fragile to be a real border. It’s a juncture created by intention and rumor, composed of insects and feathers clinging to underside of yellow air. It has nothing to do with her.” With A Good Day for Seppuku, Braverman shines a light on our most intimate relationships. It is a bracing reminder of how uniquely powerful of a writer Braverman is.